During the 1830s and 1840s, Texas found itself at the center of a heated debate over its potential statehood.

Having recently won its independence from Mexico after a bloody revolutionary war, the prospect of Texas joining the United States as a state polarized opinions across the nation.

While there was undoubtedly substantial support for annexation, particularly from slave states and advocates of westward expansion, this ambition faced formidable opposition from various quarters.

Abolitionists in the North, as well as Mexico, staunchly rejected the idea of its former province aligning with its northern neighbor, setting the stage for potential armed conflict.

In this article, we delve deeper understand who objected to Texas becoming a state within the United States.

1. The Abolitionists’ Stance

The prospect of Texas joining the United States as a slave state ignited fierce opposition from Northern abolitionists, who viewed it as a grave threat to the fragile equilibrium between slave and free states.

These ardent campaigners for the abolition of slavery recognized that admitting Texas would tilt the balance in favor of the slave-holding states, potentially enabling the expansion of the institution they so vehemently opposed.

William Lloyd Garrison’s Uncompromising Stance

Leading the charge against Texas statehood was the renowned abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, who used his famous antislavery newspaper, The Liberator, to object to the annexation of Texas.

Garrison’s uncompromising stance reflected the fears of many in the abolitionist movement that Texas’s admission would not only legitimize slavery but also pave the way for its growth into new territories.

Frederick Douglass

Douglass strongly opposed the annexation of Texas, which he saw as a conspiracy to expand slavery. In a speech in 1846, he argued that the annexation of Texas was part of a “deep and skillfully devised conspiracy” to extend the reach of slavery and the “Cotton Kingdom” all the way to the Pacific Ocean.

Douglass viewed the annexation of Texas and the subsequent Mexican-American War as a craven attempt by Southern interests to secure more territory for plantations. He was particularly critical of how some white evangelical Christians in the North justified the war and expansion of slavery as part of God’s “manifest destiny.” Douglass found this “blasphemy” and was dismayed by the silence of the evangelical clergy on these issues.

Other Northern abolitionists and anti-slavery political leaders who opposed the annexation of Texas included Joshua Giddings, Josiah Grinnell, and John P. Hale.

A Threat to Liberty and Equality

The abolitionist opposition to Texas statehood was rooted in the belief that the continued existence and potential expansion of slavery posed an existential threat to the principles of liberty and equality enshrined in the nation’s founding documents.

Reverberations Across the North

The abolitionists’ vehement opposition to the annexation of Texas reverberated across the Northern states, galvanizing a broader coalition of anti-slavery advocates.

From prominent intellectuals and politicians to influential religious leaders and ordinary citizens, the voices of dissent grew louder, warning of the moral and societal consequences of allowing the westward expansion of slavery.

The Northern anti-slavery voices, though diverse in their backgrounds and spheres of influence, were united in their belief that the admission of Texas as a slave state would not only perpetuate an abhorrent moral wrong but also sow the seeds of further division and conflict within the nation.

Their impassioned opposition, though ultimately unsuccessful in preventing annexation, laid the groundwork for the broader abolitionist movement and the eventual reckoning that would culminate in the Civil War.

2. The Presidential Opposition to Texas

President John Quincy Adams’ Stance

The prospect of annexing Texas faced staunch opposition from President John Quincy Adams and his administration.

Adams, a principled statesman and ardent abolitionist, harbored deep reservations about the potential consequences of such a move.

Chief among his concerns was the prospect of igniting a conflict with Mexico, which had only recently lost Texas after a hard-fought revolutionary war.

In 1838, Adams launched a now-famous 22-day filibuster against the annexation of Texas. He strategically used his position on the House floor to deliver a series of speeches condemning the proposal.

Adams’ speeches were multifaceted. He:

- Morally condemned slavery: He passionately argued against the expansion of slavery, which he viewed as a national sin.

- Questioned legality: He challenged the legality of annexing territory claimed by another nation (Mexico).

- Sectional Balance: He expressed concern that Texas as a slave state would upset the balance of power in the Senate, potentially leading to national disunity.

While Adams’ speeches were powerful and garnered national attention, his filibuster ultimately delayed, not stopped, the annexation. Congress adjourned for summer recess before a vote could be taken.

Long-Term Significance: Though unsuccessful in preventing annexation, Adams’ filibuster became a symbolic act of defiance against the expansion of slavery. It emboldened the anti-slavery movement and solidified his reputation as a staunch opponent of the institution

Concerns of Conflict with Mexico

Adams and his advisors were acutely aware of the precarious nature of the relationship with Mexico, and they understood that annexation could be perceived as a direct affront to Mexican sovereignty.

They feared that such a move would undermine the nation’s diplomatic efforts and jeopardize the fragile peace between the two countries.

There were also concerns that a conflict with Mexico could have far-reaching economic and political repercussions, disrupting trade and potentially drawing the United States into a protracted and costly military engagement.

Contrast with President James K. Polk’s Stance

In stark contrast to Adams’ cautious and principled stance, President James K. Polk, who assumed office in 1845, was an ardent advocate for the annexation of Texas.

Polk, a Democrat and a believer in the doctrine of Manifest Destiny, saw the acquisition of Texas as a crucial step in the nation’s westward expansion and the fulfillment of its perceived destiny to span the continent.

Dismissing concerns about potential conflicts with Mexico, Polk pursued annexation with a fervor.

He believed that the incorporation of Texas was a matter of national interest.

The contrasting positions of Adams and Polk on the issue of Texas annexation reflected the deep divisions within the nation itself.

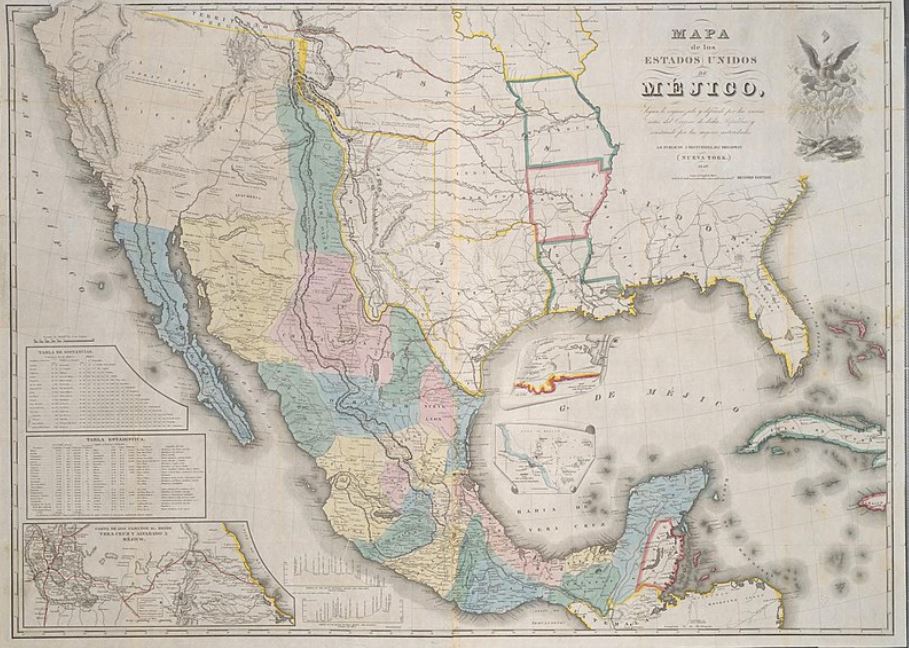

3. Mexico’s Rejection of Texas Statehood

Mexico’s Unwavering Opposition

Mexico’s response to the prospect of Texas joining the United States was one of unequivocal and vehement opposition.

Having only recently lost the territory after a bitter revolutionary war, the Mexican government viewed any attempt by Texas to align itself with its northern neighbor as a brazen affront to its sovereignty and territorial integrity.

In the aftermath of Texas’ independence, Mexico steadfastly refused to acknowledge the legitimacy of the breakaway republic, maintaining that it remained an integral part of Mexican territory.

Mexico warned that any move by the United States to annex Texas would be considered an act of war.

Tensions and the Specter of Conflict

The tensions between Mexico and the United States over the Texas issue increased, with both sides engaging in saber-rattling rhetoric.

Mexican officials, including President Antonio López de Santa Anna, issued stern warnings that annexation would be interpreted as a hostile act, potentially leading to a military response.

The prospect of war loomed large, with both sides positioning themselves for potential armed conflict.

The Mexican government began reinforcing its northern territories, while the United States bolstered its defenses along the border with Texas.

The situation was further exacerbated by the presence of American settlers in the disputed territories, adding fuel to the already combustible situation.

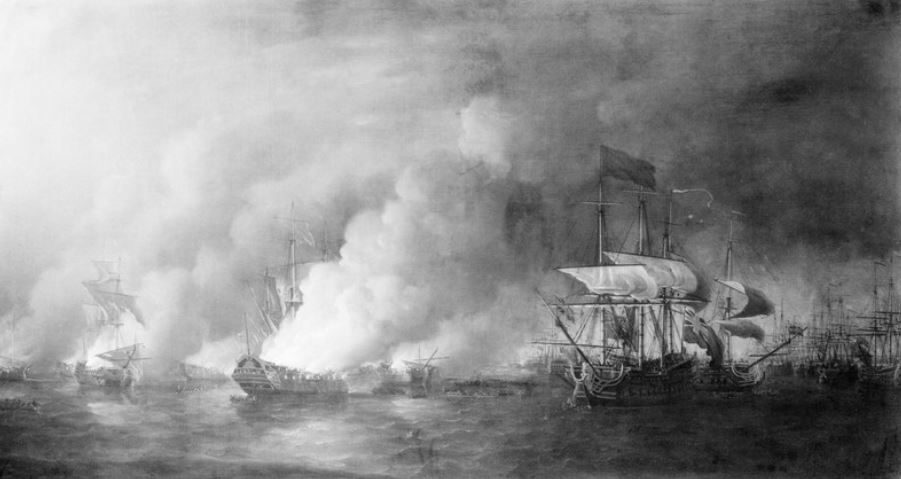

The Mexican-American War and Its Connection to Texas

The simmering tensions over Texas ultimately erupted into open conflict with the Mexican-American War of 1846-1848.

While the immediate catalyst for the war was a border dispute involving the region of Coahuila and Texas, the underlying cause was the United States’ insistence on annexing Texas, a move that Mexico had vehemently opposed from the outset.

The war proved to be a decisive victory for the United States, with Mexico forced to cede vast swaths of territory, including nearly all of the present-day American Southwest.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which formally ended the conflict, not only recognized Texas as part of the United States but also paved the way for the annexation of other territories, further fueling the expansionist ambitions of the nation.

The Mexican-American War conflict not only resolved the long-standing dispute over Texas but also laid the groundwork for the United States’ continued westward expansion, cementing its status as a continental power.

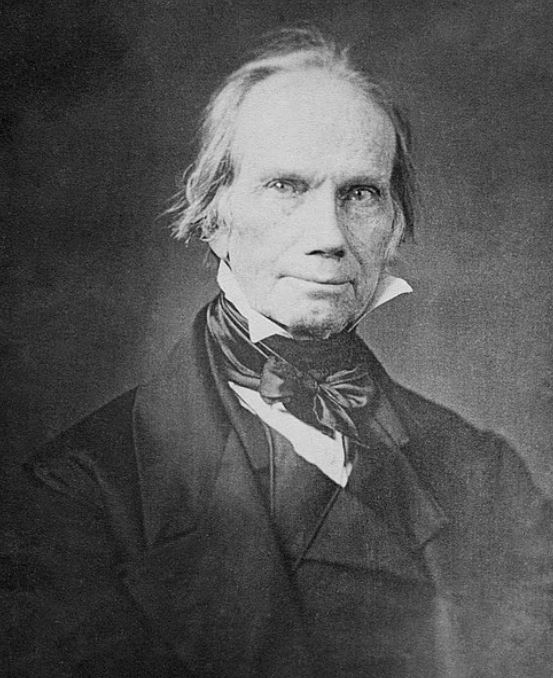

4. The Whig Party’s Apprehension

Amidst the heated debates surrounding the potential annexation of Texas, the Whig Party emerged as a formidable force of opposition, voicing grave concerns about the potential consequences of such a move.

Led by prominent figures like Henry Clay, the Whigs articulated a stance that encompassed both geopolitical and moral considerations.

Henry Clay, a prominent Whig politician and former President, strongly opposed the annexation of Texas. In his “Raleigh Letter” in 1844, Clay outlined several key objections:

- Annexation could lead to war with Mexico, which had not recognized Texas’ independence. Clay believed this would be a dishonorable and unconstitutional action.

- Annexing Texas solely to strengthen the political power of the slave states against the free states could threaten the integrity of the Union.

- While Clay did not oppose annexation in principle, he was unwilling to see the Union “dissolved or seriously jeopardized” just to acquire Texas.

- Annexation would also require the U.S. to assume Texas’ substantial national debt, which Clay saw as an impediment.

- Clay’s position put him at odds with the pro-annexation Democrats, led by James K. Polk, who went on to narrowly defeat Clay in the 1844 presidential election.

The Whigs had rallied against the annexation of another slave state, which hurt their efforts in the South..

Concerns over the Expansion of Slavery

Alongside geopolitical anxieties, the Whig Party also harbored deep reservations about the implications of Texas annexation for the contentious issue of slavery.

With Texas being a slaveholding territory, the Whigs feared that its admission as a state would upset the delicate balance between free and slave states, potentially empowering the pro-slavery factions and enabling the further expansion of the institution.

The Whigs’ opposition to annexation, though ultimately unsuccessful, laid the groundwork for the party’s subsequent transformation into a stronghold of anti-slavery sentiment, further polarizing the nation along geographic and ideological lines.

5. Annexation of Texas: Final Thoughts

The debates surrounding the potential admission of Texas as a state revealed deep cracks within the United States, with diverse groups and interests voicing their fervent opposition.

From the principled stance of President John Quincy Adams and his administration, who feared conflict with Mexico, to the Whig Party’s concerns about the expansion of slavery and the potential for war, the issue of Texas statehood exposed the complex tapestry of competing ideologies and regional interests that defined the era.

The opposition to Texas statehood, though ultimately unsuccessful in preventing annexation, had a lasting impact that reverberated through the decades.

It crystallized the growing divide between the pro-slavery South and the abolitionist North, fueling the sectional tensions that would eventually erupt into the cataclysmic Civil War.

While the voices of dissent were ultimately overshadowed by the relentless march of Manifest Destiny, their impassioned cries echoed through the ages, serving as a reminder of the enduring struggle for justice and the perpetual need to confront the moral challenges that shape a nation’s destiny.

Further Reading

If you enjoyed this article, you may be interested to read more about the American Civil War events, or perhaps read about the Mexican-American War or Texas.