Antonio López de Santa Anna was the Mexican president and general who led the forces against the Texan colonists seeking independence from Mexico in the Texas Revolution of 1835-1836.

After a series of brutal victories like the massacres at the Alamo and Goliad, Santa Anna’s army was decisively defeated by Texan forces under Sam Houston at the Battle of San Jacinto in April 1836.

Antonio López de Santa Anna himself was captured after the battle, dealing a major blow to Mexico’s efforts to stop Texas from breaking away.

Read on to find out what happened to Antonio López de Santa Anna after these incredible events in Texas.

1. Santa Anna’s Imprisonment in Texas

After his defeat at San Jacinto, Santa Anna was captured by Texan forces.

While his imprisonment wasn’t comfortable, there’s no clear evidence of extreme harshness. Facing calls for execution for his actions at the Alamo and Goliad, Santa Anna was offered a chance at freedom.

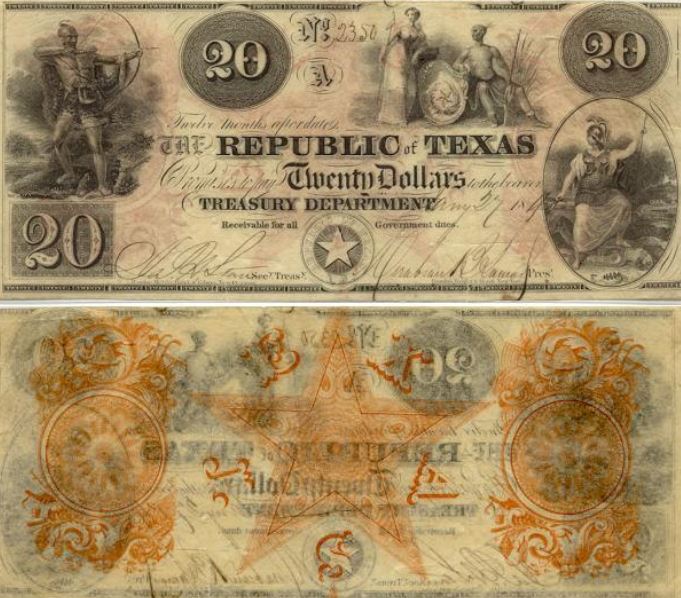

Eager for both annexation by the United States and Texan independence, Texan leaders pressured Santa Anna to sign two treaties.

One public treaty called for the removal of Mexican troops from Texas, while a secret one required him to advocate for Texan independence upon his return to Mexico. In exchange for signing, Santa Anna was promised safe passage back to Mexico.

However, fearing he would renege on the agreements, a group of Texan volunteers prevented Santa Anna’s departure and held him captive for several months, with the threat of execution still looming.

2. Santa Anna’s Transfer to Washington D.C.

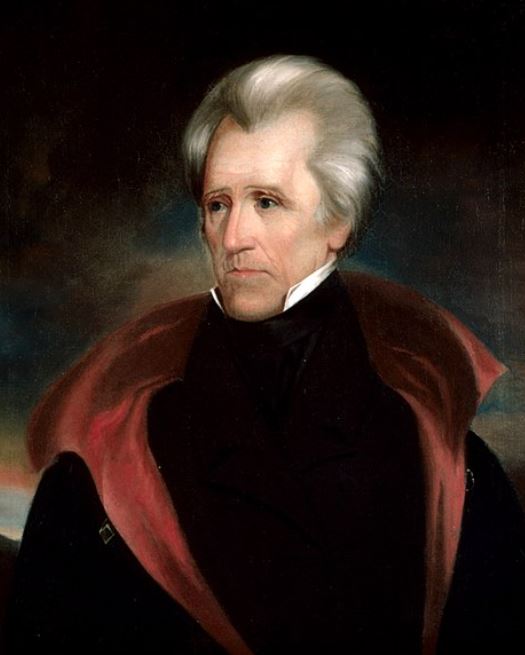

After months of captivity in Texas under the threat of execution, Santa Anna’s fate took an unexpected turn in late 1836 when President Andrew Jackson arranged for his transfer to Washington D.C.

This was part of President Andrew Jackson’s gambit to negotiate a solution to the simmering crisis over Texas between Mexico and his own aims of potential U.S. annexation of the territory.

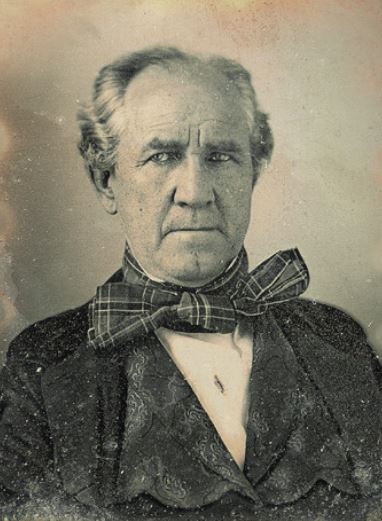

The Texan leaders like Sam Houston and Stephen F. Austin agreed to release Santa Anna into Jackson’s custody, hoping the Mexican general would leverage his leadership position to officially negotiate Texas’s independence once back in Mexico.

Their unlikely wager hinged on Santa Anna honoring his private treaties signed in Texas to facilitate this very outcome in exchange for his freedom.

In January 1837, Santa Anna was granted a series of personal meetings with the aging President Jackson in the White House.

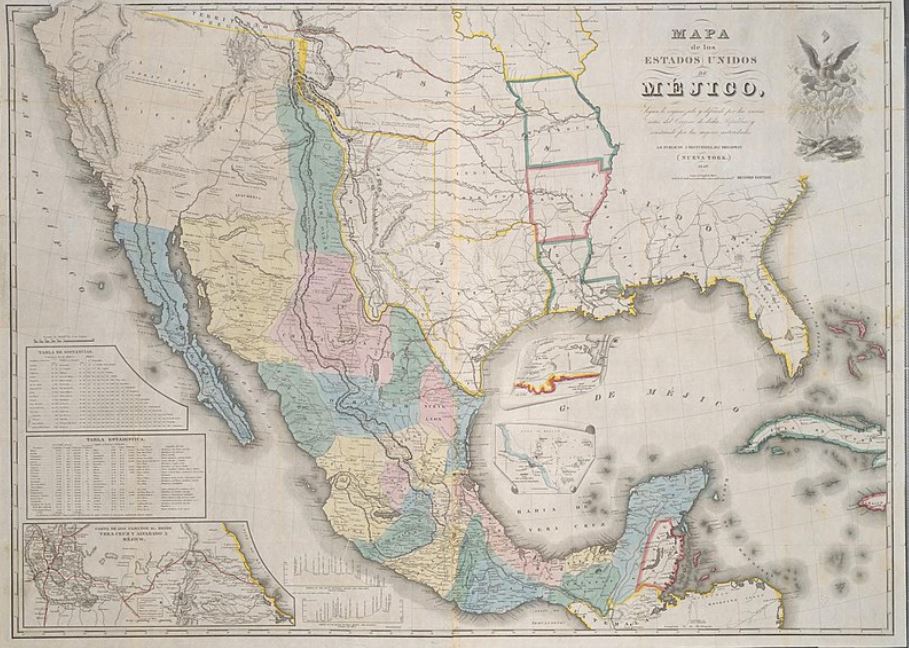

The exact details were never revealed, though Jackson was said to have proposed that Mexico cede the territories along the Rio Grande river and to the Pacific in order to solidify an independent Texas Republic.

For the United States, this offered better control over potential future expansion into those lands.

The Texan ministers in Washington like Memucan Hunt eagerly awaited the fallout of these meetings between the two nations’ leaders. They dreamed Santa Anna would push through a deal to finally severe Texas from Mexico as the key first step towards annexation by the United States soon after.

However, once safely repatriated to Mexican soil in early 1837, Santa Anna undercut any hopes of achieving the outcome the Texans had banked on from his meetings with Jackson.

He immediately disavowed making any binding agreements towards Texas independence during his imprisonment, seeing it as coerced from a captive position.

In a self-published memoir, Santa Anna defended his actions by portraying the entire Washington meeting as merely a ploy to escape captivity in Texas and potentially gain intelligence on the American position.

He asserted he had promised Jackson and the Texans nothing more than personal commitments, which he dismissed as having no rightful force on the national interests of Mexico’s government.

The Mexican general proved himself an opportunistic survivor once again in regaining his freedom without any intention of relinquishing sovereignty over the rebelling territory.

3. The “Pastry War” and Santa Anna’s Comeback

Only a year after his defeat in Texas, Santa Anna saw an opportunity to potentially redeem himself in the face of a new conflict – the “Pastry War” with France in 1838.

Though recently vilified, he remained one of Mexico’s few experienced military leaders.

The war stemmed from a complex web of issues, including a looted French pastry shop and unpaid Mexican debts to France. This provided justification for France’s naval attack on the port city of Vera cruz.

Despite his recent failures, Mexico’s government turned to Santa Anna again to lead the defense.

He enthusiastically took command, fortifying Vera cruz.

In December 1838, French forces bombarded the city’s harbor. Santa Anna’s troops fiercely defended the city, but were ultimately overwhelmed by French firepower.

During the battle, Santa Anna suffered a grievous injury – a French cannonball shattered his left leg, requiring amputation. Though Mexico ultimately conceded to French demands, Santa Anna capitalized on his injury.

He ensured his severed limb received a highly publicized military burial, portraying himself as a leader sacrificing his own body for the nation. This resonated with a public still reeling from the Texas loss.

While the “Pastry War” itself was a military defeat, Santa Anna’s injury became a potent symbol of his patriotism. It helped him rebuild his image among some Mexicans, paving the way for his return to political influence in the years to come.

4. Return to the Mexican Presidency

Riding the wave of renewed popularity from his martyrdom in the “Pastry War,” Santa Anna rapidly reasserted his political power and influence in Mexico throughout the 1840s in a recurring cycle of presidency and dictatorship.

In 1841, he helped overthrow the government of Anastasio Bustamante and was appointed as president once again. However, Santa Anna’s return to power was marred by excessive consolidation of control and authoritarian tendencies.

He brutally crushed any opposition, shuttering anti-Santa Anna newspapers and jailing dissidents. Officials and officers not seen as fully loyal were purged from the government and military ranks.

Santa Anna declared himself perpetual dictator in 1843, taking on grandiose titles like the “Most Serene Highness” and “Hero of the Nation.” He indulged in the trappings of monarchical rule, surrounding himself with noble regalia and privileges.

This cult of personality and unbridled authority predictably generated significant backlash and unrest.

Taxes were hiked to replenish the perpetually drained treasury, infuriating the populace and several states which had expected democratic reforms.

By late 1844, uprisings had erupted across Mexico in rejection of Santa Anna’s self-aggrandizing despotism.

Fearing for his life, the embattled dictator made a prudent retreat from Mexico City in December 1844. A mob desecrated the monument erected to his amputated leg, dragging its remains through the streets.

Santa Anna went into exile yet again, first taking refuge in Havana before being arrested and deported to Venezuela in 1845. His latest stranglehold over Mexico had proven unsustainable without compromise.

The cycle seemed forever destined to repeat – Santa Anna’s services required in crises only for him to overplay his hand into alienating much of the country with his l’etat c’est moi governing mentality.

5. Mexican-American War

Santa Anna’s Leadership Against U.S. Invasion

Just a year after being forced into exile again in 1845, Santa Anna was summoned back to Mexico as the nation faced an existential threat – invasion by the United States.

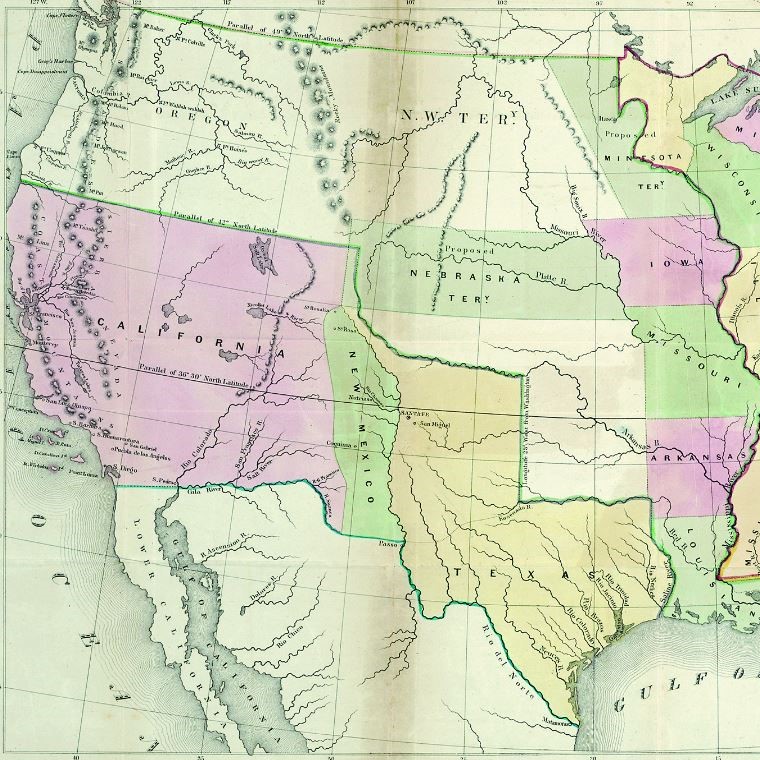

With the U.S. annexation of Texas in 1845, long-simmering border disputes boiled over into open conflict in 1846.

Despite his dictatorial excesses, Mexico’s civilian leadership turned once more to Santa Anna’s military experience to counter the American forces pushing inward.

He assumed command of the Mexican army in hopes of repelling what he saw as U.S. aggression and preventing further territorial losses.

Santa Anna initially attempted negotiations for a settlement, meeting with U.S. representatives. But talks broke down, and by early 1847 he was leading Mexican troops into the first major battles against the invading American forces.

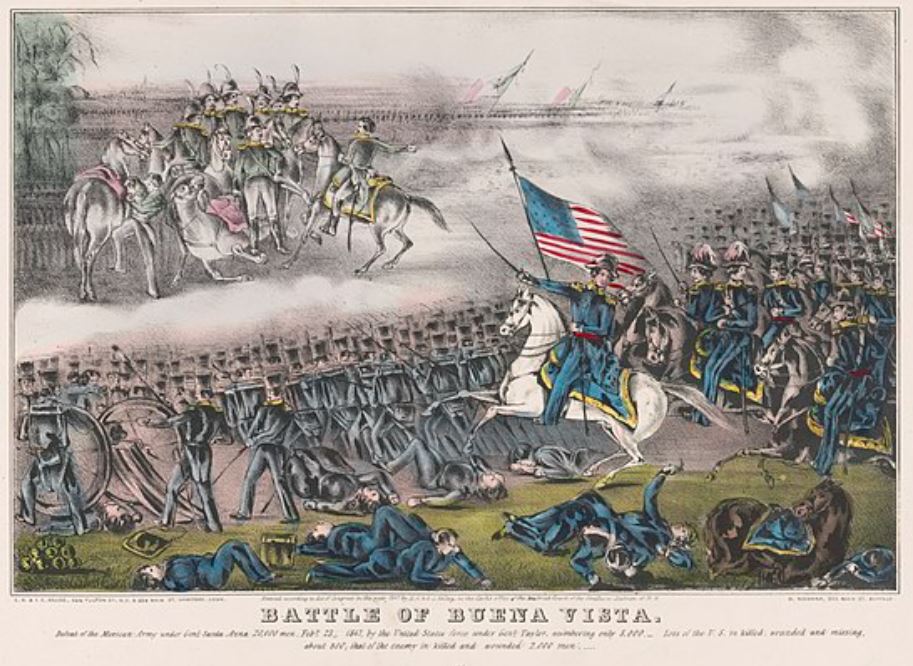

Defeats at Buena Vista and Cerro Gordo

Santa Anna’s first major engagement against the U.S. army came at the Battle of Buena Vista in February 1847. Despite outnumbering the American forces, Santa Anna’s troops could not dislodge them and were forced into retreat after two days of heavy fighting.

Undeterred, Santa Anna regrouped and formulated new defenses along the route to Mexico City at the village of Cerro Gordo. But his forces were outmaneuvered by the brilliant American commander Winfield Scott.

Santa Anna’s defensive lines were flanked and routed in a stunning defeat in April 1847.

This loss shattered Santa Anna’s hopes of blocking the American advance on the Mexican capital.

In the chaos of Cerro Gordo, Santa Anna’s prosthetic cork leg was captured by Illinois infantry, becoming a famous symbol of the American victory.

The Fall of Mexico City

As Scott’s army pushed on towards Mexico City, Santa Anna frantically assembled new defensive forces. But they could not resist the American onslaught at successive battles in Contreras, Churubusco, and Molino del Rey outside the capital.

In September 1847, U.S. forces overwhelmed the Mexican fortifications at Chapultepec Castle and entered Mexico City itself, an iconic moment represented in paintings and memorials.

Santa Anna had failed to halt the invasion.

With the American capture of Mexico City, Santa Anna’s military was in ruins.

The subsequent Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 forced Mexico to cede nearly half its national territory to the United States, including the present-day Southwest and California.

For Santa Anna, the Mexican-American War represented his greatest military failure. The defeats he suffered enabled the massive loss of Mexican lands and national humiliation at the hands of the United States – his legacy forever tarnished.

6. Final Presidency and Gadsden Purchase

After years spent scheming and lobbying from exile following his losses in the Mexican-American War, Santa Anna found one last opportunity to regain power in Mexico in 1853.

A conservative rebellion sparked by Catholic clergy had overthrown the liberal government under the Plan de Hospicio.

The rebel leaders, desperate for stability and strength, turned once again to the aging Santa Anna as a rallying figure despite his checkered past. In March 1853, at age 59, he was elected president for an incredible eleventh term.

The Gadsden Purchase Controversy

From the outset, Santa Anna’s new administration faced a dire financial crisis, with an empty treasury and weakened economy due to the costly American war.

To raise funds, he entered into secret negotiations with the U.S. over the sale of Mexican territory along the border region.

What emerged was the infamous Gadsden Purchase of 1854, where the U.S. acquired nearly 30,000 square miles of present-day southern Arizona and New Mexico for $10 million.

The goal was to gain land for a potential southern transcontinental railroad route.

However, the deal quickly became mired in allegations of corruption.

Santa Anna was accused of pocketing much of the purchase money rather than directing it into state coffers. There were also claims he vastly undervalued the lands to American negotiators.

For Mexico, it represented another humiliating territorial loss compounding the grievous impacts of the recent American invasion and occupation. The Gadsden Purchase became a flashpoint highlighting Santa Anna’s self-enrichment at his country’s expense.

Overthrow and Final Exile

Public outrage over the Gadsden sale helped catalyze the next phase of Santa Anna’s ongoing cycle of downfall.

A liberal revolution sparked by the Plan of Ayutla targeted his removal from power in 1855.

Facing overwhelming opposition, the increasingly enfeebled Santa Anna resigned the presidency in August 1855 and fled into exile, this time taking up residence in Colombia. His latest grasps at authority had crumbled as quickly as they materialized.

The Gadsden Purchase represented the last jaw-dropping act of territorial alienation overseen by Santa Anna. After clawing his way back into power time and again, the controversy cemented his legacy as an opportunistic leader who regularly put self-interest before that of his nation.

7. Santa Anna’s Later Life and Death

Lengthy Exiles Across the Americas

Following his ouster from the Mexican presidency in 1855, Santa Anna spent nearly two decades in exile, wandering between Cuba, the United States, Colombia and other nations.

These were largely lonely years where he schemed unsuccessfully for a way to regain power and influence in Mexico.

In the late 1860s, Santa Anna briefly allied himself with French forces who had installed Maximilian I as ruler of Mexico. He hoped siding with Maximilian would pave the way for his return. But the French puppet regime quickly collapsed in 1867, forcing Santa Anna to remain in exile.

For a time, he lived in Staten Island, New York, trying to raise funds for a private military force to retake Mexico City by force. These efforts went nowhere, and in 1874 at age 80, a nearly blind Santa Anna decided to take advantage of an amnesty offered by the Mexican government.

Return to Mexico City and Death

Santa Anna returned to Mexico City in July 1874 after nearly 20 years in exile across the Americas. He came back a frail, elderly man – a shell of the brash military strongman who had repeatedly grasped power over the decades.

In the twilight of his life, Santa Anna resided in Mexico City relatively unbothered. He spent his final years compiling memoirs reflecting on his tumultuous career until passing away on June 21, 1876 at age 82.

Santa Anna received a full military funeral befitting his once lofty standing.

His remains were interred in a glass coffin at the capital’s Panteón de San Fernando cemetery. It was a fittingly ambiguous farewell for such a divisive historical figure – honored for past service yet equally reviled by many for his excesses and losses.

Despite the reverential burial, Santa Anna’s grave was looted and destroyed just months later in October 1876 – a final indignity suggesting the polarized legacy he left behind in Mexico.

For a man who so frequently clawed his way into power, Santa Anna’s story ultimately ended in prolonged exile before a quiet, unmourned demise in the capital he had once dominated.

Further Reading

If you enjoyed this article, you may be interested to read more about Mexican territories lost to the United States, or perhaps read about the events of the Mexican-American War.