In an era when most European kingdoms relied on loose feudal alliances and personal loyalties, late Anglo-Saxon England developed a remarkably sophisticated system of governance. By the reign of Æthelred the Unready (978-1016), the English state could mobilize national armies, collect standardized taxes, and enforce laws with an efficiency that would not be seen elsewhere in Europe for centuries.

This administrative machine didn’t emerge by accident. It was forged through two centuries of Viking invasions, royal reforms, and bureaucratic innovation.

The system proved so effective that both the Danish conqueror Cnut (1016-1035) and later the Norman William the Conqueror (1066-1087) maintained its core structures largely intact.

At its height, this system enabled Æthelred to raise the staggering sum of £16,000 in silver to pay off Viking raiders (equivalent to about 10% of England’s annual GDP at the time) and allowed his son Edmund Ironside to field multiple armies against Danish invaders in 1016 despite the kingdom’s desperate straits.

Read on to find out how this centralized system developed.

1. The Foundations: Alfred the Great’s Reforms (871-899)

The Viking Crisis and Military Reorganization

When Alfred became king of Wessex in 871, he inherited a realm on the brink of collapse.

Viking armies had conquered Northumbria, East Anglia, and most of Mercia. The traditional Anglo-Saxon military system – based on regional militias led by local nobles – had proven woefully inadequate against the highly mobile Viking forces.

Alfred’s revolutionary response created the framework for England’s later administrative success:

The Burh System – Alfred established a network of at least 33 fortified towns (burhs) across Wessex, strategically placed so no settlement was more than 20 miles (a day’s march) from protection. Each burh had:

- Defensive walls and garrison

- Mint for coinage

- Market and administrative center

Archaeology shows these were carefully planned. Wall lengths corresponded to the number of men needed for defense (about 4 men per meter), with maintenance responsibilities assigned to specific landholdings.

Standing Army Reforms – Alfred divided the fyrd (militia) into two rotating forces:

- One half on active duty

- Other half tending farms

This maintained agricultural production while keeping defenses ready.

Naval Innovation – Alfred also built England’s first royal fleet, with ships designed to intercept Viking longships in coastal waters.

Administrative Backbone

Alfred strengthened existing structures while adding new bureaucratic elements:

Shire System – Counties (shires) were governed by ealdormen (high-ranking nobles) but monitored by royal officials.

Shire Reeves (Sheriffs) – These royal appointees oversaw:

- Law enforcement

- Tax collection

- Military muster

Legal Reforms – Alfred issued a comprehensive law code emphasizing loyalty to the crown over local lordship. His introduction of regular royal assemblies (witans) created a forum for national policy-making.

Educational Revival – Alfred established a court school to train administrators and promoted English literacy to improve record-keeping.

2. The 10th Century: Danegeld and the Tax System

The Hide System: Foundation of Anglo-Saxon Taxation

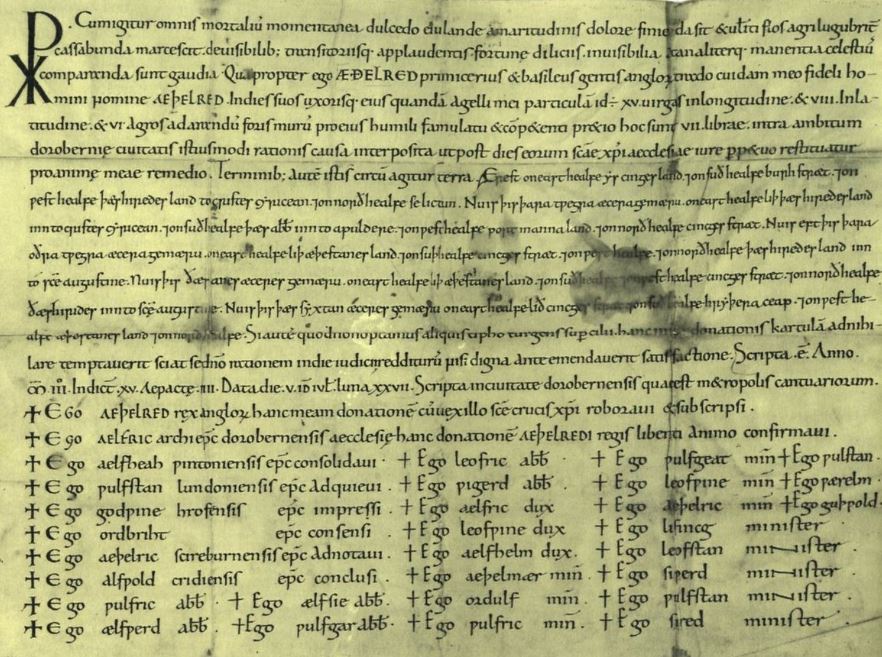

At the heart of England’s remarkable tax-collecting ability was the hide – a unit of land assessment that formed the basis for Danegeld payments. While notionally representing enough land to support one family (typically about 120 acres), hides varied significantly in actual size and quality across regions.

Their true purpose was as a standardized unit for taxation rather than precise land measurement.

The system’s sophistication becomes clear when examining how Danegeld evolved:

- Pre-1016: Collected as emergency tribute to buy off Viking invaders

- Post-1016: Institutionalized as permanent land-tax for national defense

- Norman Period: Continued until the 12th century as general revenue

The Rising Cost of Viking Extortion

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records increasingly massive payments:

991 – 10,000 Roman pounds (3,300 kg) of silver after Battle of Maldon

994 – £16,000 to Sweyn Forkbeard and Olaf Tryggvason

1002 – Another major payment (exact amount unspecified)

1007 – 36,000 troy pounds (13,400 kg) for two years’ peace

1012 – 48,000 troy pounds (17,900 kg) after Canterbury’s sack

1018 – Cnut’s massive 82,500 pounds (30,800 kg) payout

These payments weren’t called “Danegeld” at the time – contemporaries used the Old English term gafol (tribute). The Normans later applied the Danegeld label retroactively.

Collection and Administration

The tax machinery developed remarkable efficiency:

- Assessment: Each shire’s hides were recorded in detailed surveys

- Rate Setting: Kings determined payment per hide based on need

- Collection: Sheriffs gathered funds through shire courts

- Verification: Royal officials monitored compliance

The system was so effective that:

- It raised £2400 in 1129-30 (10% of royal revenue)

- William the Conqueror used it to fund his continental wars

- Henry I taxed it annually at 2 shillings per hide

Scandinavian Impact and Evidence

Viking runestones boast of receiving Danegeld:

- U 344 (Orkesta, Sweden): Commemorates Ulf of Borresta taking three Danegelds

- Sö 260: Mentions a Viking voyage funded by English silver

- Numerous hoards of English coins found across Scandinavia

Archaeologists estimate Vikings extracted some 60 million pence (over 100 tonnes of silver) from England – a staggering sum that transformed the Scandinavian economy.

Comparative Context

England wasn’t alone in paying protection money:

- Finland, Estonia and Latvia paid similar tributes to Swedes

- Slavic tribes paid Varangians until their rebellion

- Iberian taifa kingdoms paid gold to Christian states

But England developed the most sophisticated system for:

- Regular assessment

- National collection

- Monetary payment (rather than goods)

Legacy and Decline

The system’s flexibility allowed it to endure:

- Exemptions: Used as royal favors (London freed in 1133)

- Adjustments: Rates changed based on circumstances

- Replacement: Eventually superseded by movable property taxes

When Henry II finally abandoned Danegeld in 1162, it marked the end of a system that had:

- Funded England’s defense for nearly two centuries

- Created Europe’s most advanced tax bureaucracy

- Left permanent marks on English governance

3. The Military Machine: Raising Armies in Anglo-Saxon England

The Fyrd System – Unlike contemporary European feudal levies, England maintained a national defense system:

Select Fyrd

- Professional warriors serving in rotation

- Equipped by landowners (5 hides = 1 fully armed man)

- Could be mobilized quickly

General Fyrd

- All able-bodied men could be called

- Local defense focus

Housecarls (Post-1016)

- Elite professional troops introduced by Cnut

- Built on existing Anglo-Saxon structures

Logistics and Deployment

The burh network enabled rapid response:

- Garrison troops in each burh

- Pre-positioned supplies

- Roads connecting defensive sites

Records show armies could be mustered in weeks, with coordinated movements across shires.

4. Why England’s Government Was Unique

While France and Germany fragmented, England centralized because:

Geographical Factors – Compact size aided control and Roman road network remained usable

Viking Threats – Constant danger forced innovation and National response required coordination

Cultural Factors – Strong tradition of royal authority and the Church provided literate administrators

Conclusion: A Lasting Legacy

The Anglo-Saxon administrative system proved so robust that William the Conqueror retained it virtually intact, using it to produce the Domesday Book (1086) – Europe’s first national census. Its legacy endured in:

- The English Exchequer

- County sheriff system

- Common law traditions

This was not just a government for its time, but the foundation of English governance for centuries to come.

Further Reading

If you enjoyed this article, you may enjoy these:

- What happened to Edgar the Aetheling?

- Kings and Queens of England Ranked from Worst to Best

- How did Charlemagne improve the lives of people in Europe?

- Why was the crowning of Charlemagne so important?

- Were the Princes in the Tower bodies ever found?

You may also enjoy these articles about Medieval Europe: