Winter is a season filled with celebrations. Around the world, Christmas dominates much of the western tradition. But centuries before Christmas became the central winter holiday, the Romans celebrated Saturnalia. This was a wild and exuberant festival honoring the god Saturn, laid the foundation for Christmas as we know it today.

Let’s explore Saturnalia and its profound influence on modern Christmas traditions.

1. What Was Saturnalia?

Saturnalia was an ancient Roman festival dedicated to Saturn, the god of agriculture and time.

It took place annually in mid-December, coinciding with the winter solstice. Originally a modest agricultural festival, it eventually transformed into a week-long extravaganza of feasting, gift-giving, and revelry.

The festival officially began on December 17th and lasted several days. It marked the end of the harvest season and a time to honor Saturn’s golden age—a mythical era of abundance and equality.

Public ceremonies, sacrifices, and private gatherings were all part of the celebrations.

The heart of Saturnalia was the idea of turning the world upside down, with traditional roles and social norms were reversed. Slaves were treated as equals, and the poor could indulge in luxuries. This subversion of order added to the festival’s unique charm.

2. The Origins of Saturnalia

Saturnalia’s roots can be traced back to ancient agricultural rituals. Initially, it was a day of thanksgiving for the year’s final harvest. Roman priests would honor Saturn by unwrapping his statue from woolen bindings and placing it on a couch within his temple.

This symbolic act represented rebirth and renewal.

As Rome expanded and Greek influences shaped its culture, Saturnalia evolved. The Roman Saturn was equated with the Greek god Cronus, both associated with rebirth and the promise of a golden age.

By the 3rd century BCE, Greek practices were integrated into Saturnalia. The festival became fixed on December 17th, ensuring a structured observance.

Over time, Saturnalia grew in popularity.

Its duration was extended from one day to a full week. The festival became a centerpiece of Roman life, drawing people from rural areas into the city. Public spaces were transformed with decorations and temporary structures to accommodate the influx of celebrants.

3. How Saturnalia Was Celebrated

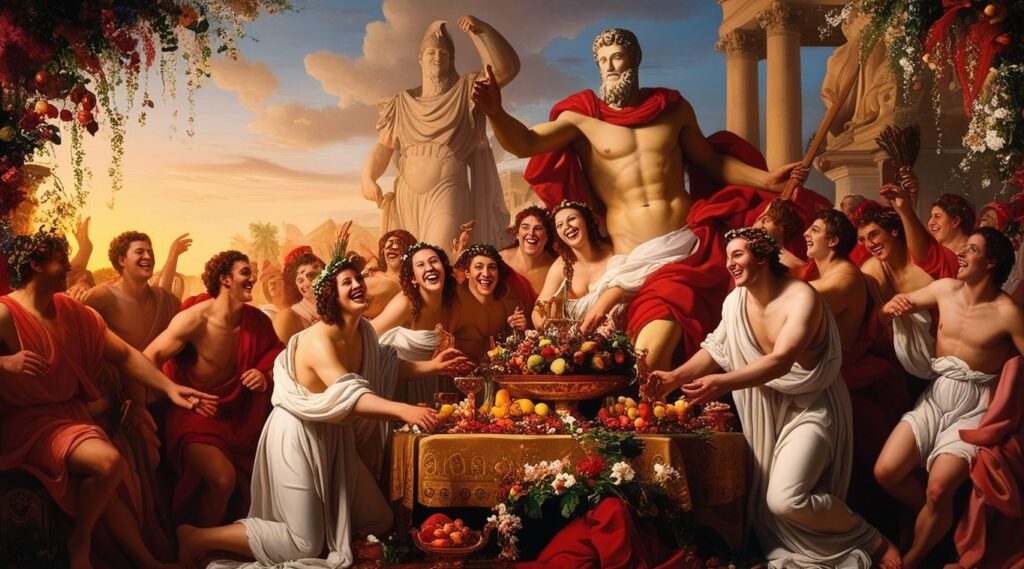

Saturnalia was an extravagant festival, combining deeply rooted religious traditions with spirited, often unrestrained revelry. The event was a cornerstone of Roman culture, celebrated with such grandeur and enthusiasm that it became one of the most anticipated times of the year.

A Grand Start: Processions and Sacrifices

The festival commenced with a spectacular procession through the streets of Rome.

The procession was a visual feast, featuring priests in ceremonial garb, senators in their finest togas, and crowds of citizens enthusiastically participating.

Bulls, often adorned with garlands, were led through the city to the Temple of Saturn in the Roman Forum. These animals were destined for sacrifice, an offering to Saturn, the god of wealth, abundance, and agriculture.

The Temple of Saturn itself became a focal point of the celebrations.

After the sacrifices, the statue of Saturn, normally bound in woolen ropes throughout the year to symbolize the restrained flow of time, was ceremoniously unbound, signifying a release of abundance and joy.

The act was symbolic of Saturn’s reign during the mythological Golden Age—a time when humanity lived in harmony, free from toil and suffering.

A Community Feast in the Forum

Following the sacrifices, a lavish public feast was held, often in the Roman Forum.

Tables were laden with roasted meats, bread, fruits, and wine, generously provided by the state or wealthy patrons.

This communal meal was open to all, reflecting Saturnalia’s spirit of inclusivity and abundance. For many, this feast was a rare opportunity to indulge, particularly for the lower classes who might not otherwise experience such luxury.

A Pause in Daily Life

During Saturnalia, the rhythms of Roman life shifted dramatically.

Public offices, law courts, and schools were closed, signaling a temporary cessation of civic duties. Even declarations of war were deferred—a significant gesture in a society often embroiled in military campaigns.

This suspension of daily activities underscored the importance of the festival and allowed all citizens, regardless of status, to partake in the celebrations.

The Spirit of Role Reversal

One of the most unique and defining aspects of Saturnalia was its temporary inversion of social norms.

Slaves, who were usually at the bottom of the social hierarchy, were granted an extraordinary degree of freedom during the festival. For a brief period, they dined alongside their masters and were treated as equals. This practice, while not erasing the realities of slavery, provided a momentary respite and a symbolic nod to the ideals of the Golden Age when all were equal.

The role reversal extended beyond shared meals.

Masters often performed tasks typically relegated to slaves, such as serving food or attending to household chores. Slaves were even allowed to speak freely, sometimes offering playful critiques of their masters without fear of retribution.

The “King of Saturnalia”

A playful highlight of the celebrations was the selection of a “King of Saturnalia.”

This figure, often chosen from the lower ranks of society or even among the slaves, was given mock authority. The King’s role was to issue lighthearted and humorous commands, which everyone, including the elite, was expected to obey.

These commands could range from silly tasks to playful games, further enhancing the festival’s atmosphere of mirth and equality.

Gambling and Games

Another hallmark of Saturnalia was the widespread playing of games, particularly dice, which were otherwise frowned upon or outright banned in Roman society.

Gambling became a central activity, indulged in by people of all social classes. Small tokens or coins were often used as stakes, and the normally rigid rules against betting were temporarily lifted.

The games symbolized the festival’s embrace of chance and unpredictability, echoing the themes of reversal and chaos.

Gifting Traditions

Gift-giving was another beloved tradition during Saturnalia.

Romans exchanged small presents known as sigillaria—figurines made of wax or clay, as well as more practical items like writing tablets, combs, or warm clothing.

The gifts were often accompanied by short poems or jokes, emphasizing the festive and lighthearted nature of the exchange. Wealthier individuals might give more elaborate gifts, but the spirit of Saturnalia emphasized thoughtfulness and fun over extravagance.

Music, Dance, and Merriment

The streets and homes of Rome were alive with music and dance throughout the festival.

Revelers sang carols, some of which were dedicated to Saturn, while others were humorous and raucous.

These early carols bear a resemblance to modern Christmas traditions, particularly in their communal and joyful spirit. Drunken celebrations and spontaneous dancing were common, creating an atmosphere of unbridled joy and community.

In every corner of Rome, Saturnalia was a time for laughter, camaraderie, and celebration. Its blend of solemn rituals and unrestrained revelry made it a cherished and unforgettable festival for Romans of all classes.

4. Saturnalia’s Influence on Christmas

The transformation of Saturnalia into aspects of the Christian celebration of Christmas reflects how ancient traditions often evolve rather than disappear.

When Christianity became the dominant religion of the Roman Empire in the 4th century CE, the Church faced the challenge of converting a population steeped in deeply ingrained pagan rituals.

Saturnalia, one of the most beloved festivals, was no exception. Instead of outright abolishing such a popular event, Christian leaders found it more effective to repurpose and integrate its customs into the new faith.

Timing: A Strategic Move

One of the most apparent links between Saturnalia and Christmas is the timing of the celebrations.

Saturnalia, traditionally observed from December 17th to the 23rd, culminated just a few days before the Christian feast of the Nativity.

Christmas was officially set on December 25th by Pope Julius I in the 4th century CE. This date coincided with the Roman festival of Dies Natalis Solis Invicti—the “Birthday of the Unconquered Sun”—which celebrated the winter solstice and the rebirth of light.

By aligning Christmas with existing festivals, the Church made the transition to Christianity smoother for the Roman populace.

This overlap allowed Christian celebrations to coexist with longstanding pagan festivities, gradually leading to the blending of traditions.

For many Romans, adopting Christmas may have felt like an extension of Saturnalia rather than a wholesale replacement.

Feasting and Merrymaking

The feasting and merriment that characterized Saturnalia were seamlessly carried over into early Christmas traditions.

Saturnalia’s lavish communal meals, with tables overflowing with food and drink, inspired the festive banquets that became central to Christmas celebrations. Families and communities gathered to share meals, a tradition that remains a cornerstone of the holiday season today.

This emphasis on abundance during the darkest days of winter also served a symbolic purpose, representing hope and renewal as the days began to lengthen.

The joyous, convivial atmosphere of Saturnalia found a natural home in the spirit of Christmas.

Gift-Giving

Gift-giving, a hallmark of Saturnalia, transitioned effortlessly into Christmas customs.

During Saturnalia, Romans exchanged small, meaningful gifts known as sigillaria—wax or clay figurines, candles, and other tokens of goodwill. This practice mirrored the generosity and sharing that would later define Christmas.

In early Christian observances, gift-giving was often linked to the story of the Magi bringing gifts to the infant Jesus.

Over time, this tradition expanded, with St. Nicholas—a figure rooted in Christian hagiography—becoming the legendary bringer of gifts. The spirit of Saturnalia, with its focus on generosity and thoughtfulness, undoubtedly influenced this evolution.

Greenery and Decorations

Saturnalia also contributed to the tradition of decorating homes with greenery.

During the Roman festival, households were adorned with garlands, wreaths, and boughs of evergreen plants like holly and ivy. These symbols of life and vitality were believed to ward off evil spirits during the dark winter months.

Christian celebrations adopted this custom, with evergreens eventually taking on new symbolic meanings.

The Christmas tree, which gained prominence centuries later, echoes these early practices of decorating with greenery.

Role Reversal and the Feast of Fools

The Saturnalian custom of role reversal—where slaves were treated as equals and masters served their servants—left a lasting impression on medieval Christian celebrations.

This practice evolved into the Feast of Fools, a raucous festival observed in parts of Europe during the 12th century. Like Saturnalia, the Feast of Fools involved temporary role reversals, humorous commands issued by a chosen “Lord of Misrule,” and an atmosphere of joyful chaos.

Although the Church eventually sought to suppress the Feast of Fools for its irreverent tone, its influence is still felt in modern traditions that emphasize humor, equality, and breaking from routine during the holiday season.

The Evolution of Santa Claus

Even the modern figure of Santa Claus bears echoes of Saturnalia’s traditions.

The Roman god Saturn, associated with abundance, wealth, and generosity, shares thematic parallels with Santa Claus as a benevolent figure who brings joy and gifts.

Additionally, the red and white pileus cap worn by Roman revelers during Saturnalia finds a curious parallel in Santa’s iconic red and white hat.

While the imagery of Santa Claus has evolved significantly, particularly in the 19th and 20th centuries, it’s not hard to trace the threads back to Saturnalian festivities.

5. The Universal Appeal of Winter Celebrations

Saturnalia was more than just a festival; it was a reflection of Roman values and a celebration of life’s abundance. Its influence on Christmas is a testament to the resilience of cultural traditions.

Saturnalia’s enduring popularity highlights the universal human desire to celebrate during the darkest days of the year. Feasting, gift-giving, and communal joy are themes that transcend cultures and eras. These customs provide warmth and connection, offering a beacon of hope as the year draws to a close.

While Saturnalia itself faded with the fall of the Roman Empire, its spirit lives on.

Christmas, with its blend of sacred and secular traditions, continues to bring people together in celebration. By understanding Saturnalia, we gain a deeper appreciation for the rich tapestry of history that shapes our modern holidays.

As you gather with loved ones this Christmas, remember the ancient Romans who, centuries ago, lit candles, exchanged gifts, and shouted “Io Saturnalia!” in the spirit of joy and unity. The echoes of their festivities remind us that, no matter the era, the heart of winter celebrations remains the same: togetherness, generosity, and hope for the future.

Further Reading

You may also enjoy these articles: