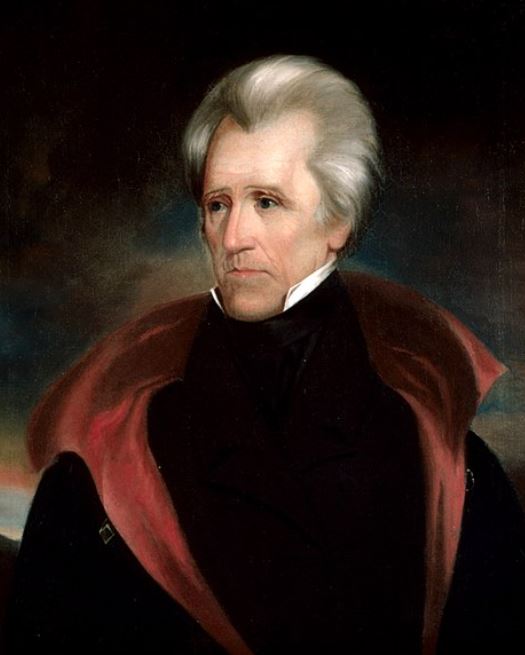

Andrew Jackson’s presidency, spanning from 1829 to 1837, was a pivotal period in American history. A man of strong convictions and populist appeal. However, his economic policies had far-reaching consequences that extended well beyond his time in office.

These policies would ultimately contribute to one of the worst economic crises in American history: the Panic of 1837.

This article will explore how President Andrew Jackson’s actions, particularly his war on the Second Bank of the United States, the issuance of the Specie Circular, and the distribution of the government surplus, led to this devastating economic downturn.

1. President Andrew Jackson’s War on the Second Bank of the United States

President Andrew Jackson’s Distrust of Banks and Paper Money

Throughout his life, President Andrew Jackson harbored a deep suspicion towards banks and financial institutions.

He blamed them for the boom and bust cycles that often led unfortunate citizens into debt and ruin.

This view was reinforced by the Bank of the United States’ handling of the economic crisis of 1819, which seemed to confirm Jackson’s worst fears about the dangers of centralized financial power.

President Andrew Jackson’s distrust of paper money stemmed from his belief that only gold and silver (specie) constituted real currency. He saw paper money as a tool that banks used to manipulate the economy for their own benefit, often at the expense of ordinary citizens.

The Veto of the Bank’s Charter Renewal in 1832

The Second Bank of the United States, established in 1816, was due for charter renewal in 1836.

However, in 1831, Henry Clay, President Andrew Jackson’s political rival, advised Bank President Nicholas Biddle to seek an early renewal of the charter.

Clay anticipated that Congress would approve the renewal, forcing Jackson to either accept it or veto it.

Clay, who had been nominated as the presidential candidate for the National Republican Party for the 1832 election, wanted to fight the election as a referendum on the future of the Bank.

As Clay had predicted, Congress approved the Bank’s recharter in 1832.

President Andrew Jackson, true to his convictions, vetoed the bill. In his veto message, Jackson argued that the Bank was unconstitutional and that it favored the wealthy elite over the common people.

This populist message resonated with many Americans and contributed to Jackson’s landslide victory in the 1832 election.

Removal of Federal Deposits from the Bank in 1833

Not content with merely vetoing the Bank’s recharter, President Andrew Jackson took further action to weaken the institution.

In 1833, on the advice of Attorney General Roger Taney, Jackson decided to withdraw Treasury deposits from the national bank and instead deposit them in smaller state banks, which became known as “pet banks.”

When President Andrew Jackson’s Treasury Secretary William Duane refused to carry out this order, Jackson dismissed him and appointed Taney as acting secretary. Taney then carried out the transfer as planned on October 1, 1833.

This move significantly weakened the Second Bank of the United States and set the stage for the financial instability that would follow.

Nicholas Biddle, in response to President Andrew Jackson’s actions, tightened credit in an attempt to demonstrate the Bank’s economic power. This led to a brief recession, but by the spring of 1834, the economy had largely recovered.

2. Distributing the Surplus

Accumulation of Government Surplus

By 1836, the federal government had accumulated a significant surplus.

This was due to several factors, including increased land sales (before the Specie Circular), tariff revenues, and the general economic boom of the mid-1830s.

On January 1, 1835, President Andrew Jackson proudly announced that the federal government had paid off its debts, leaving a substantial surplus in the Treasury.

Decision to Distribute Surplus to State Banks

With this large surplus on hand, Congress passed the Deposit and Distribution Act in June 1836.

This act called for the distribution of the surplus revenue to the states in four quarterly installments, beginning in January 1837.

President Andrew Jackson, despite some misgivings, signed the bill into law.

The surplus was to be distributed to state banks, which were then supposed to lend it out to stimulate local economies.

Inflation and Speculation

The distribution of the surplus had unintended consequences. It led to a rapid expansion of credit as state banks, flush with federal funds, increased their lending.

This easy credit fueled further speculation, particularly in land and commodities.

This inflationary spiral was precisely what President Andrew Jackson had hoped to avoid with the Specie Circular. However, the combination of the surplus distribution and the sudden requirement for specie payments created a volatile economic situation. The stage was set for a severe economic contraction.

3. The Specie Circular of 1836

The Specie Circular was an executive order issued by President Andrew Jackson on July 11, 1836. This order required that all purchases of federal land be made with gold or silver coin (specie) rather than paper money or bank notes.

Reasons for Issuing the Executive Order

President Andrew Jackson issued the Specie Circular for several reasons. Primarily, he was concerned about the rampant speculation in western lands.

Easy credit provided by state banks had fueled a land boom, with speculators buying up large tracts of land using paper money, often with the intention of quickly reselling at a profit.

President Andrew Jackson believed that requiring payment in specie would curb this speculation and ensure that only genuine settlers who had saved real money would be able to purchase land.

He also hoped it would reduce the circulation of paper money, which he distrusted, and encourage the use of gold and silver coin.

Immediate Effects on Land Sales and the Economy

The effects of the Specie Circular were immediate and severe.

Land sales plummeted as speculators and settlers alike found themselves unable to come up with the required gold or silver. This sudden drop in demand led to a sharp decrease in land values.

The circular also put immense pressure on banks, particularly in the West.

Many of these banks had issued large amounts of paper currency backed by little specie. As demand for specie increased, these banks struggled to meet withdrawal requests, leading to a liquidity crisis.

The Specie Circular effectively popped the speculative bubble that had been building in the land market.

While this was President Andrew Jackson’s intention, the abruptness of the change sent shockwaves through the entire economy, contributing significantly to the panic that would unfold in 1837.

4. The Panic of 1837

The Panic of 1837 was the result of a perfect storm of economic factors, many of which were directly related to President Andrew Jackson’s policies.

The war on the Second Bank of the United States had removed a stabilizing force from the economy. The distribution of the surplus had fueled speculation and inflation. The Specie Circular had then suddenly contracted the money supply and crashed land values.

International factors also played a role.

A financial crisis in Great Britain led to a drop in cotton prices, hurting American exports. British banks also began to call in American debts, putting further pressure on the U.S. financial system.

Onset of the Panic in 1837

The panic began in earnest in May 1837, just months after President Andrew Jackson left office.

Banks in New York City, facing a run on their gold and silver reserves, suspended specie payments. This suspension quickly spread to banks around the country.

The suspension of specie payments meant that banks would no longer exchange their paper notes for gold or silver.

This led to a rapid depreciation of paper money and a severe contraction of credit.

Businesses found themselves unable to secure loans, leading to widespread bankruptcies.

Severity and Duration of the Resulting Depression

The Panic of 1837 led to one of the worst depressions in American history up to that point.

Unemployment soared, with some estimates suggesting that up to 25% of the workforce was jobless in some areas.

Prices for agricultural goods plummeted, causing hardship for farmers. Banks failed, businesses closed, and construction projects were abandoned.

The depression lasted for several years.

While some regions began to recover by 1839, a second banking crisis in 1839 prolonged the economic downturn. Many areas didn’t fully recover until the mid-1840s.

The severity of the crisis was compounded by the lack of federal response.

Martin Van Buren, President Andrew Jackson’s successor, adhered to the principle of limited government intervention in the economy. This meant that there was little in the way of federal relief or stimulus to help alleviate the economic pain.

5. Long-term Consequences

Impact on the Banking System

The Panic of 1837 and President Andrew Jackson’s policies had lasting effects on the American banking system.

The demise of the Second Bank of the United States left the country without a central bank until the creation of the Federal Reserve in 1913.

This absence of a central monetary authority made the financial system more vulnerable to panics and less able to respond effectively to crises.

In the wake of the crisis, many states passed “free banking” laws.

These laws allowed anyone meeting certain minimal requirements to open a bank and issue currency.

While intended to democratize banking, this system led to a proliferation of state banks and a chaotic array of bank notes in circulation, each with varying degrees of reliability.

The crisis also led to a long-lasting distrust of paper money among many Americans. This sentiment would influence debates over monetary policy for decades to come, including the arguments over bimetallism in the late 19th century.

Impact on Future Economic Policy

The Panic of 1837 and its aftermath had a significant impact on future economic policy in the United States. It demonstrated the dangers of an unregulated banking system and the need for a more stable currency.

Future presidents became more cautious about interfering with the banking system.

The crisis highlighted the importance of sound economic management and the potential consequences of drastic policy changes.

The experience of the 1837 crisis also influenced the development of more sophisticated economic theories. Economists and policymakers began to study more closely the relationships between credit, currency, and economic stability.

In the longer term, the crisis contributed to the eventual establishment of a more robust federal role in managing the economy. While this change would take decades to fully materialize, the Panic of 1837 was an important step in the evolution of American economic policy.

7. Final Thoughts: The Devastating Legacy of Jackson’s Economic Meddling

President Andrew Jackson’s economic policies stand as a stark warning against unchecked executive power and misguided populism.

His war on the Second Bank of the United States, fueled by personal vendettas and a simplistic understanding of finance, obliterated a crucial stabilizing force in the economy. The reckless distribution of the surplus and the ill-conceived Specie Circular reveal a president more concerned with ideological purity than economic stability.

Jackson’s actions were not merely misguided; they were catastrophically irresponsible.

His distrust of paper money and established financial institutions betrayed a fundamental ignorance of modern economic principles. The resulting Panic of 1837 was not an unforeseen consequence, but a direct result of his ham-fisted interventions.

The true legacy of Jackson’s economic policies is one of widespread suffering and decades of financial instability. His administration stripped the nation of its ability to manage economic crises effectively. In his crusade against perceived financial tyranny, Jackson subjected the American people to the real tyranny of economic collapse.

History must judge Jackson’s economic leadership harshly. It stands as a testament to the dangers of allowing populist rhetoric and personal biases to dictate national economic policy.

Further Reading

If you enjoyed this article about How President Andrew Jackson Caused the Economic Crisis of 1837. You may be interested to read more about the early American history, such as:

- President Andrew Jackson and the Removal of Native Americans

- Andrew Jackson: The Tyrant President

- Did the Confederacy have the Legal Right to Secede from the Union?

- What Was the California Gold Rush of 1849?

- Who Owned Alaska Before Russia?

- Who Won the Battle of Alamo?

- Did the Mexican-American War lead to the Civil War?

You may also enjoy these articles about the early modern history: