The Seven Years’ War (1754–1763) was a monumental global conflict that spanned continents and changed the course of history.

In North America, it is known as the French and Indian War, a clash between the British and the French, with various Native American tribes allied with each side.

This war had far-reaching consequences, particularly for Britain’s relationship with its American colonies. The war’s aftermath left Britain in massive debt and led to policies that deeply alienated the colonies, setting the stage for the American Revolution.

To fully understand how these tensions unfolded, keep reading and explore the key moments that ignited a revolution.

1. Background of the Seven Years’ War

The Seven Years’ War began as a fight for the Ohio River Valley, a region of strategic importance and economic potential.

Both Britain and France claimed ownership of this territory, seeing it as vital to expanding their colonial empires. The fertile lands of the valley promised lucrative opportunities for farming and trade, especially in fur.

The conflict was not just between European powers.

Native tribes who lived in the Ohio River Valley also became deeply involved. For them, it was a fight to protect their ancestral lands and maintain control over crucial trade routes.

The war saw alliances form along cultural and strategic lines, with British forces partnering with the Iroquois Confederacy and French forces aligning with the Algonquin and other Native American tribes.

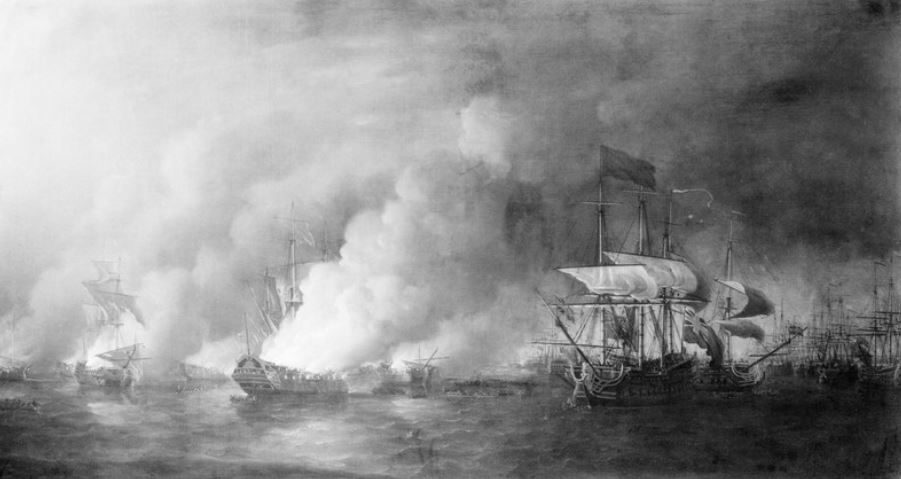

Initial skirmishes broke out as both sides built forts to assert dominance.

Tensions escalated in 1754 when George Washington led a failed attempt to expel the French from the region. This marked the beginning of open hostilities that spread far beyond the Ohio River Valley, evolving into a global war involving Europe, Asia, and the Caribbean.

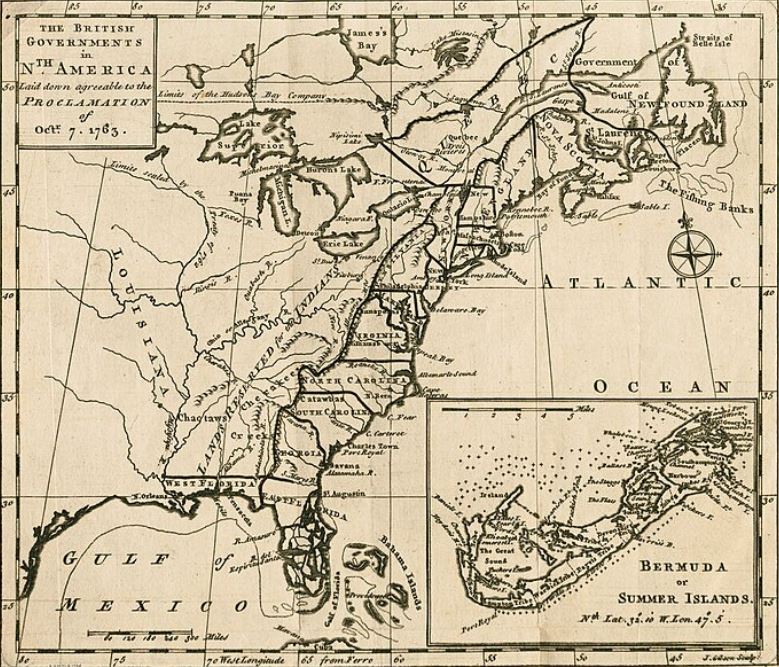

The conflict in North America culminated in 1763 with the Treaty of Paris.

Under this agreement, Britain gained control of French Canada and all lands east of the Mississippi River.

Spain, a French ally, received Louisiana as compensation.

France’s power in North America was almost entirely eliminated, leaving Britain as the dominant colonial power on the continent. However, this victory came at a cost, setting the stage for future conflicts between Britain and its American colonies.

2. The Seven Years War’s Impact on the Colonies

Economic Strains

The Seven Years’ War caused severe economic disruptions for the American colonies.

Trade routes were blocked or heavily restricted due to the conflict. Many colonial merchants found it difficult to export goods, particularly to Europe, which was embroiled in war. This left colonies with surplus products and fewer markets to sell them.

The British government’s debt soared as a result of financing the war.

Colonial economies also suffered as British soldiers occupied towns and villages. Troops required supplies, housing, and food—often at the expense of local residents. This further strained relationships between colonists and the British government.

Military Tensions

During the war, colonial militias fought alongside the British army. While they shared victories, the partnership was far from harmonious. British officers often looked down on colonial troops, considering them poorly trained and undisciplined. This attitude created friction and bred mistrust.

Colonial soldiers, in turn, were frustrated by the British military’s rigid hierarchy. They resented being treated as second-class participants despite their significant contributions. For example, colonial militias were instrumental in key battles, such as the capture of French forts in the Ohio River Valley.

The war also exposed differences in military strategy.

British forces relied on formal, organized tactics suited to European battlefields. In contrast, colonial militias used guerrilla warfare, adapting to the rugged terrain of North America. This clash of approaches highlighted cultural and operational divides.

The unequal treatment of colonial troops left a lasting impression. Many colonial leaders, including future revolutionaries like George Washington, came to view British military authority with suspicion and disdain. This mistrust would later fuel resistance during the American Revolution.

3. Territorial Issues after the Seven Years’ War

The end of the war brought significant territorial changes.

Britain gained vast new lands, including French Canada and territory east of the Mississippi River. Colonists, eager to expand, saw these lands as a reward for their sacrifices during the war.

However, the British government had other plans.

The Proclamation of 1763 prohibited settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains. This policy aimed to prevent conflicts with Native American tribes by limiting colonial expansion.

For many colonists, the proclamation felt like a betrayal.

They had fought and died to secure these lands, only to be told they could not settle there. The decision was deeply unpopular and widely ignored. Thousands of settlers defied the proclamation, moving westward in search of new opportunities.

The territorial restrictions also created economic challenges. Land speculation had been a major industry for colonial elites, who had hoped to profit from selling western lands. The proclamation halted these ambitions, further angering influential colonists.

In summary, the key territorial issues included:

- The Proclamation of 1763 restricting westward expansion.

- Frustration among settlers and land speculators.

- Growing defiance of British authority in frontier regions.

These territorial disputes contributed to a sense of alienation and distrust between Britain and its colonies.

4. Post-War British Policies after the Seven Years’ War

The conclusion of the Seven Years’ War left Britain with a staggering national debt. To alleviate this financial burden, the British government turned to its American colonies as a source of revenue.

The first major measure was the Sugar Act of 1764, which imposed taxes on sugar and molasses imported into the colonies. This act aimed to regulate trade and increase revenue, but it quickly drew the ire of colonial merchants and consumers alike.

The situation escalated with the introduction of the Stamp Act of 1765, which required colonists to purchase special stamped paper for printed materials such as newspapers, legal documents, and even playing cards.

Unlike the Sugar Act, which primarily affected merchants, the Stamp Act impacted nearly every colonist, making its effects far-reaching and highly visible.

The Emergence of “No Taxation Without Representation”

Colonists were infuriated by these new taxes, especially because they had no say in their implementation.

They had no representatives in the British Parliament to advocate for their interests or oppose the new measures. This lack of representation led to the rallying cry of “no taxation without representation,” which became a unifying slogan for colonial resistance.

Protests erupted across the colonies.

Merchants organized boycotts of British goods, crippling trade.

Colonial assemblies passed resolutions denouncing the taxes as unconstitutional.

Grassroots organizations like the Sons of Liberty mobilized public opinion through pamphlets, speeches, and demonstrations. In some cases, protests turned violent, with mobs targeting tax collectors and burning their effigies.

The widespread unrest forced Britain to reconsider.

In 1766, Parliament repealed the Stamp Act, but the victory was short-lived. The repeal was accompanied by the Declaratory Act, which asserted Britain’s right to legislate for the colonies “in all cases whatsoever.” This declaration sowed the seeds of further conflict.

The Townshend Acts and Escalating Resentment

Just a year later, Britain introduced the Townshend Acts of 1767, imposing indirect taxes on imported goods like glass, paper, paint, and tea. These taxes reignited colonial outrage.

Although they were technically different from the direct taxes of the Stamp Act, colonists still viewed them as an infringement on their rights.

The response was swift and organized. Boycotts resumed, targeting British imports.

Women played a key role in these efforts, forming groups like the Daughters of Liberty to produce homemade goods and reduce dependence on British products. Colonial newspapers circulated passionate arguments against the taxes, further fueling public resistance.

British officials underestimated the depth of colonial dissatisfaction. They believed the Townshend Acts would be easier to enforce than the Stamp Act, but they underestimated the unity and determination of the colonies.

Increased Military Presence

To maintain order and enforce its policies, Britain stationed a standing army in the colonies after the war.

The presence of these troops was a constant source of tension. Under the Quartering Act of 1765, colonists were required to house and supply British soldiers. This placed a financial and logistical burden on local communities, further straining relations.

The presence of soldiers in colonial towns was often seen as an occupation.

Clashes between troops and colonists were frequent, with tensions boiling over in incidents like the Boston Massacre in 1770. In this event, British soldiers fired into a crowd of protesting colonists, killing five people.

The massacre became a potent symbol of British tyranny and was widely publicized in colonial newspapers, fueling anti-British sentiment.

Building Colonial Unity

Initially, the colonies were divided. Each had its own government, economy, and priorities.

However, shared grievances began to bring them together. The economic hardship caused by British taxes, the restrictions on westward expansion, and the tensions with British troops created common ground.

The Albany Plan of Union, proposed by Benjamin Franklin in 1754, was one of the first attempts at colonial unity.

While it was not adopted, it laid the groundwork for future cooperation. By the 1760s, colonies began forming committees of correspondence to share information and coordinate resistance to British policies.

The Stamp Act Congress of 1765 marked another milestone. Representatives from several colonies met to organize opposition to the Stamp Act. Although the congress did not achieve immediate success, it demonstrated the potential for collective action.

5. The Path to Revolution

The path to the American Revolution was a long, tense, and contentious journey, marked by a series of escalating conflicts and misunderstandings between the American colonies and Britain.

The conflict was sparked and fueled by a combination of direct actions, such as the Boston Tea Party and the imposition of the Intolerable Acts, as well as deeper issues related to British mismanagement of the colonies and the resentment left by the aftermath of the Seven Years’ War.

The frustration with British interference, along with growing desires for autonomy, would eventually push the colonies toward the ultimate break from Britain.

Boston Tea Party (1773)

One of the most iconic and rebellious events in American history, the Boston Tea Party, took place in 1773 and became a powerful symbol of colonial resistance against British authority.

It was not merely a protest over tea—it was about asserting colonial rights and challenging British control over the colonies.

- The British government had passed the Tea Act of 1773, which granted the British East India Company a monopoly on tea sales in the American colonies. This was an effort to save the struggling company by allowing it to sell surplus tea directly to the colonies, bypassing colonial merchants.

- Although the British claimed the Tea Act would lower the price of tea, the colonists saw it as just another form of taxation without representation. The principle of “no taxation without representation” had become a central grievance for the colonies, and the Tea Act was seen as an extension of this unjust practice.

In response to the Tea Act, a group of colonial patriots, dressed as Native Americans to conceal their identities, boarded three British ships in Boston Harbor. There, they dumped 342 chests of tea—valued at about £10,000—into the harbor. This bold act of defiance not only damaged British property but also sent a clear message that the colonies would not accept British economic control or tax impositions without their consent.

The British response to the Tea Party was swift and severe.

They saw the destruction of the tea as an act of rebellion, and in retaliation, they took drastic steps to reassert their control over the colonies. But what the British failed to understand was that their harsh measures only deepened the colonists’ resolve and fueled the growing desire for independence.

The Intolerable Acts (1774)

In direct retaliation to the Boston Tea Party, Britain enacted the Intolerable Acts in 1774, a series of laws aimed at punishing Massachusetts and reasserting British authority. The British hoped these measures would quell the unrest and discourage further acts of rebellion.

The key provisions of the Intolerable Acts were:

- The Boston Port Act – Closed Boston Harbor until the destroyed tea was paid for, effectively crippling the city’s economy.

- The Massachusetts Government Act – Dissolved the Massachusetts colonial assembly and gave the British governor more control over the local government.

- The Administration of Justice Act – Allowed British officials accused of crimes to be tried in Britain rather than in Massachusetts, which many colonists saw as an attempt to shield British soldiers from justice.

- The Quartering Act – Expanded the 1765 Quartering Act, forcing colonists to provide housing and supplies for British soldiers stationed in the colonies.

Rather than isolating Massachusetts and deterring other colonies from rebelling, the Intolerable Acts had the opposite effect. They unified the colonies in their opposition to British tyranny. Colonists across the thirteen colonies saw the harshness of these measures as an attempt to strip them of their rights and freedoms.

In response, the colonies convened the First Continental Congress in 1774, with delegates from all thirteen colonies. The Congress issued a Declaration of Rights and Grievances, demanding the repeal of the Intolerable Acts and asserting their right to self-governance. They also called for a boycott of British goods, in an effort to economically pressure Britain into changing its policies.

The Intolerable Acts revealed to the colonists just how far Britain was willing to go to maintain control.

This event reinforced the growing belief that colonial interests were being ignored and undermined by the British government, pushing many toward the conclusion that independence was the only way forward.

British Mismanagement and Colonial Resentment

A crucial factor in the escalation of tensions was British mismanagement of colonial affairs. For much of the early colonial period, Britain adopted a relatively hands-off approach to governing the American colonies, allowing them a degree of self-rule and autonomy. However, as the colonies grew in economic and political importance, Britain began to assert more direct control, often without understanding the complexities of colonial life and governance.

Key examples of British mismanagement that contributed to colonial resentment include:

- Increased Taxation – After the costly Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), Britain faced a massive national debt. To alleviate the financial burden, the British government began to impose taxes on the colonies, starting with the Sugar Act (1764), which taxed sugar and molasses imports. This was followed by the Stamp Act (1765), which taxed paper goods and legal documents, and the Townshend Acts (1767), which levied duties on a variety of goods such as glass, paint, and tea.

- No Representation in Parliament – The imposition of these taxes was a direct violation of the colonies’ right to self-governance, as they had no representatives in the British Parliament. Colonists saw these taxes as an infringement on their rights, leading to the slogan “No taxation without representation.” The colonies had grown accustomed to governing themselves, and British attempts to tax them without their consent was deeply resented.

- Failure to Address Grievances – When colonial leaders petitioned the British government to repeal these taxes or grant them representation in Parliament, they were met with indifference or hostility. The British response was to increase military presence in the colonies and impose further restrictions, rather than listening to colonial concerns. This failure to engage in meaningful dialogue deepened the divide and created a sense that Britain was out of touch with colonial realities.

This mismanagement, combined with a growing sense of colonial identity and a desire for greater autonomy, pushed the colonies toward rebellion. The increasing interference in colonial governance and trade served to highlight the disconnect between the interests of the colonies and the policies of the British government. For many colonists, the lack of British responsiveness confirmed that their future lay outside the realm of British control.

5. Final Thoughts: The Legacy of the Seven Years’ War

The Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), also known as the French and Indian War in North America, had far-reaching consequences for the relationship between Britain and its colonies. The war, which pitted Britain against France, left Britain with massive war debts and an expanded military presence in the colonies.

While the war initially united the colonies in a common cause against a shared enemy, its aftermath revealed several significant issues:

- Financial Burden – To pay off the war debts, Britain began imposing new taxes on the colonies, which were resented as unfair.

- Increased Military Presence – The British stationed large numbers of troops in the colonies to protect their territories, but many colonists saw this as an occupation force rather than a defense against external threats.

- Colonial Self-Reliance – The war had demonstrated that the colonies were capable of organizing their own military forces and defending themselves. This fostered a sense of independence and self-reliance that would later fuel demands for autonomy from Britain.

The Seven Years’ War had a profound effect on colonial attitudes, shifting them toward a more unified sense of identity. It laid the groundwork for the eventual push for independence, as many colonists began to see Britain not as a protective ally but as an oppressive power that stifled their growth and autonomy.

The road to the American Revolution was paved with escalating tensions, mismanagement, and a growing desire for independence. The events of the Boston Tea Party and the Intolerable Acts, coupled with British failures to respect colonial autonomy and address their grievances, created a volatile situation.

The experience of the Seven Years’ War had fostered a sense of unity among the colonies and made clear their ability to self-govern. As a result, the colonists began to see independence not only as a possibility but as a necessity. The path to revolution was thus set, and it would soon culminate in the open rebellion that would shape the future of the United States.

Further Reading

If you enjoyed this article, you may enjoy these: