The American Civil War is often viewed as a conflict confined within America’s borders, between the Union and Confederate states. However, the war had significant reverberations across the globe, including Britain and France.

Britain and France, the two major European powers at the time, debated intervention in the war. Ultimately both countries opted for neutrality, though popular opinion was mixed.

This article will examine the varied responses in Britain and France to America’s defining internal conflict of the 19th century.

- 1. Disrupted Cotton Trade with Britain and France

- 2. Complex Pressures Around Confederate Diplomatic Recognition

- 3. Diplomatic Crisis: The Trent Affair

- 4. Limited Aid to the Confederacy

- 5. Decisive Union Victories Dissuade Foreign Intervention

- 6. Geo-Politics Beyond American Shores

- 7. Final Thoughts: Britain and France: Walking a Tightrope

- Further Reading

1. Disrupted Cotton Trade with Britain and France

The American Civil War disrupted the cotton trade between the Southern United States and Britain and France.

These countries relied heavily on raw cotton imports to supply their massive textile mills and fuel domestic textile industries.

This vital supply was abruptly cut off by the naval blockade imposed by the Union during the war. The resulting “Cotton Famine” devastated British and French textile production.

With limited alternative cotton suppliers available, mills were forced to shut down, throwing thousands out of work.

Both Britain and France had major incentives to intervene and break the blockade to restore cotton imports and protect their economies.

However, they stopped short of direct military action.

The impacts on the textile industry swayed political debates but did not dictate policy outright.

In Britain, textile workers and manufacturers lobbied heavily for intervention, while abolitionists argued that Britain should not support the Confederacy and slavery.

Meanwhile, Napoleon III of France flirted with recognizing and aiding the Confederacy, but pulled back to maintain relations with the Union.

Economic dependence on Southern cotton was ultimately not enough to induce Britain or France to actively intervene and enter the war themselves.

Though devastated in the short-term, both nations’ textile sectors recovered by finding alternative cotton supplies and modernizing mills in the long run.

2. Complex Pressures Around Confederate Diplomatic Recognition

While the cutoff of Southern cotton imports dealt a heavy blow to British and French textile industries, diplomatic considerations with the United States ultimately outweighed these trade disruptions.

Britain was wary of antagonizing the Union and disrupting peaceful relations.

Though Britain relied heavily on Southern cotton, the Union remained an important trade partner for other goods. Provoking conflict could also undermine Britain’s neutrality stance on the slavery issue. Additionally, Britain had to consider Canada’s security should war break out with the Union.

For Napoleon III’s France, meddling in the Civil War presented an opportunity to expand international influence amid its rise as an imperial power. Intervention may have also drained military resources from more pressing concerns in Mexico.

While strained at times, both nations fundamentally prioritized maintaining relations with the U.S. above short-term trade interests. This pragmatic calculation would prevail through to the end of the American Civil War.

3. Diplomatic Crisis: The Trent Affair

The Trent Affair brought Britain and the Union to the brink of open war in late 1861.

On November 8th, the USS San Jacinto intercepted the British mail ship RMS Trent and detained two Confederate diplomats, James Mason and John Slidell, who were en route to Britain and France to press the South’s cause overseas.

Outraged by this illegal boarding of a neutral ship and violation of free navigation, the British government demanded an apology and release of the prisoners under threat of war.

War fever swept Britain, with public outrage and bellicose calls to teach the Union a lesson.

British forces in Canada were expanded in preparation to attack the Union from the north.

Prime Minister Lord Palmerston explored an opportunity to divide the United States and establish greater British influence on the continent. However, cooler heads like Foreign Minister Lord Russell urged restraint, fearing the costs of another transatlantic war.

In Washington, Lincoln’s cabinet also debated responding with defiance or concession to avoid conflict.

Ultimately pragmatism prevailed, and Lincoln shrewdly backed down, stating the Union captain had acted without authorization. Mason and Slidell were released in January 1862, averting British entry into the war.

This diplomatic resolution underscores how neither side ultimately sought open war, despite posturing. This prudent diplomacy kept the Civil War an internal struggle rather than expanding into a globe-spanning war.

4. Limited Aid to the Confederacy

While withholding formal recognition, Britain and France still provided limited covert support to the South.

British shipbuilders constructed fast blockade runners to evade Union blockades and sustain Southern cotton exports and wartime imports.

Weapons manufacturers funneled arms to the Confederacy against Union protests.

British and French bankers and financiers facilitated loans to the rebel Confederate government.

This discreet involvement fell short of enabling a Southern victory. But it reflected opportunism to profit from war demand and maintain commercial ties.

For Britain, clandestine support appeased powerful textile interests clamoring for Southern cotton. France’s aid aligned with Napoleon III’s intrigues to empower the Confederacy as a counterweight to growing American power.

Ultimately, the calculated risks of covert support proved preferable to direct intervention for Britain and France.

It allowed them to nominally maintain neutrality while still courting Southern trade and cotton. However, both nations trod carefully to avoid provoking the Union into larger confrontation. Their prudent balancing act would last throughout the bloody four-year struggle.

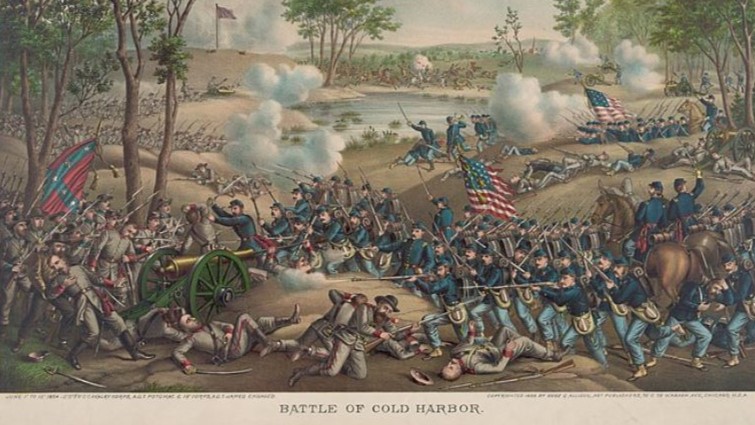

5. Decisive Union Victories Dissuade Foreign Intervention

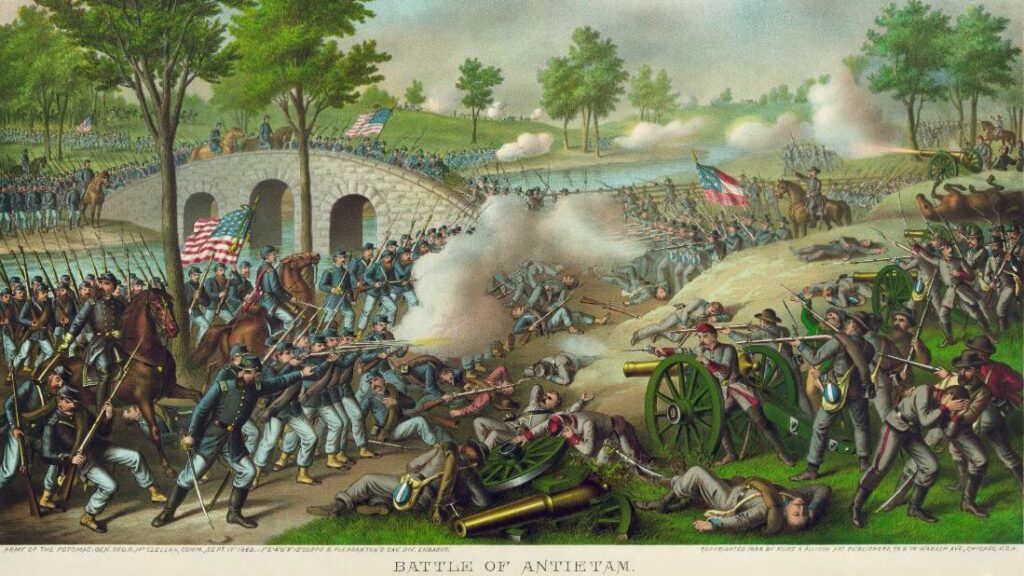

In 1862 and 1863, critical battlefield victories by the Union Army convinced Britain and France that the Confederacy lacked the strength and prospect of victory needed to warrant diplomatic recognition or intervention.

This dissuaded both nations from taking actions that may have altered the course of the Civil War.

The Battle of Antietam in September 1862 proved a pivotal moment. This bloody one-day battle halted Robert E. Lee’s first invasion of the North and led Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, signaling slavery’s eventual demise.

This transformational Union moment convinced Britain that the South likely could not prevail in its bid for independence. Abolitionist sympathies also discouraged British intervention on behalf of a now openly pro-slavery Confederacy.

The following July, the Battle of Gettysburg marked another vital turning point.

Lee’s second invasion of the North was repulsed after three days of ferocious fighting, blunting the Confederacy’s offensive power at great cost of life.

With Lee forced to retreat, any real hope of British military intervention on the South’s behalf evaporated. The enormous toll of death and carnage at Gettysburg also shocked both Britain and France.

In the wake of these two crucial Union successes, it became increasingly clear that Southern defeat was probably only a matter of time. Britain and France saw little strategic interest left in backing the Confederacy’s faltering bid for independence.

6. Geo-Politics Beyond American Shores

While the American Civil War (1861-1865) certainly presented opportunities for European intervention, several other geopolitical events across the globe also played a role in preventing Britain and France from decisively engaging in the conflict.

France’s costly Mexican intervention (1861-1867)

Napoleon III’s Mexican intervention, fueled by dreams of a French-backed empire and countering US power, turned into a six-year quagmire that cost France dearly.

While early victories bolstered his image, establishing control proved difficult. Mexican guerrilla resistance, led by Benito Juárez, and vast distances plagued the French army.

Tropical diseases like yellow fever further decimated their ranks.

The financial burden mounted, straining the French treasury and angering taxpayers.

Public support dwindled as the intervention dragged on with no clear end in sight.

By 1866, the Mexican venture left France weakened, its prestige tarnished, and Napoleon III’s grip on power shaken.

Increasing German Nationalism

While the American Civil War raged (1861-1865), across the Atlantic, another powerful force was brewing: German nationalism.

The fragmented Germanic states yearned for unification, mirrored by the United States’ struggle for national integrity. This burgeoning German nationalism became a major preoccupation for France, fearing a powerful neighbor on its doorstep.

France, under Napoleon III, initially supported the Confederacy, hoping to weaken both the US and Prussia (a leading German state). However, growing Prussian victories and German unification sentiment worried France. They saw a unified Germany as a potential threat to their dominance in Europe.

This concern was amplified by Prussia’s aggressive leader, Otto von Bismarck, who advocated for “blood and iron” unification. France felt increasingly isolated, surrounded by a rising and potentially hostile Germany.

Therefore, while the American Civil War captivated international attention, the rise of German nationalism, fueled by unification aspirations and Prussian ambition, emerged as a major concern for France, shaping European power dynamics and foreshadowing future conflicts.

Conflicts Across the British Empire

While the American Civil War (1861-1865) drew global attention, Britain’s vast empire simultaneously grappled with numerous conflicts, like the Taiping Rebellion in China (1850-1864), acting as a significant “drain” on their resources and military capacity, hindering potential intervention in the US.

- The Taiping Rebellion: This massive civil war in China pitted the Qing Dynasty against the Christian-inspired Taiping Heavenly Kingdom. It consumed immense resources and manpower, with estimates of 20-30 million casualties. Britain, with economic interests in China, was cautiously involved, providing some support to the Qing but wary of escalating involvement.

- Beyond China: Rebellions and uprisings simmered across other parts of the British Empire, demanding attention and troops. In India, the Sepoy Mutiny (1857-58) posed a major challenge, requiring significant military force to quell. Additionally, conflicts in Africa, New Zealand, and other colonies further stretched British resources thin.

Britain’s expansive empire, entangled in various conflicts worldwide, limited its ability to decisively intervene in the American Civil War. The Taiping Rebellion serves as a prime example of how these global commitments diverted resources and attention away from the US theater, shaping the complex geopolitical landscape of the era.

7. Final Thoughts: Britain and France: Walking a Tightrope

While avoiding direct military intervention, Britain and France still played pivotal and complex roles on both sides of the American Civil War.

Their stances balanced textile economic interests, regional power dynamics, domestic political pressures, and diplomacy. The war highlighted America’s growing global influence and forced Britain and France to walk a fine line between rivals.

Further Reading

If you enjoyed this article, you may be interested to read more about the American Civil War events, or perhaps read about the bloodiest battles of the Civil War or the South’s important victories. Read here for more general American history.