The Mexican-American War was not the sole cause of the American Civil War, but it added significant fuel to the fire.

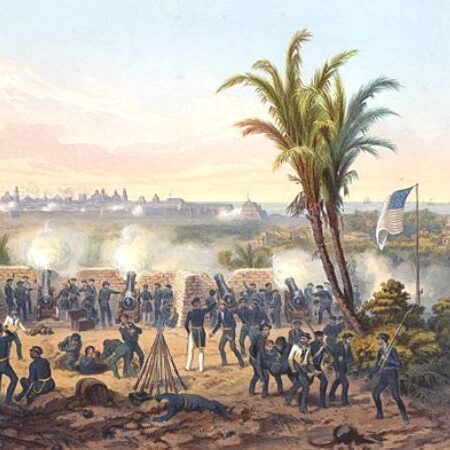

From 1846-1848, U.S. forces battled Mexico and eventually gained control of vast western territories. This ignited the issue of whether those lands would be open to slavery or free soil. It opened economic, political, and moral divisions between the North and South over the expansion of slavery.

In this article, we explore how this often-overlooked conflict contributed to the causes of the Civil War.

1. The Mexican-American War of 1846-1848 and its outcome

The Mexican-American War had its roots in the 1845 annexation of Texas by the United States.

Texas had been an independent republic after rebelling against Mexico in 1836.

When the U.S. annexed the former Mexican territory in 1845, Mexico refused to recognize the loss of its breakaway province and viewed it as an act of aggression against Mexico’s territorial rights.

Tensions escalated after annexation when the U.S. sent troops into the disputed territory between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande, which Mexico considered part of its national boundaries.

In April 1846, a group of Mexican cavalry attacked a U.S. patrol in this region, triggering the outbreak of the Mexican-American War.

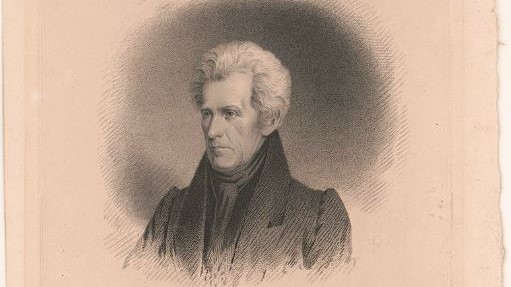

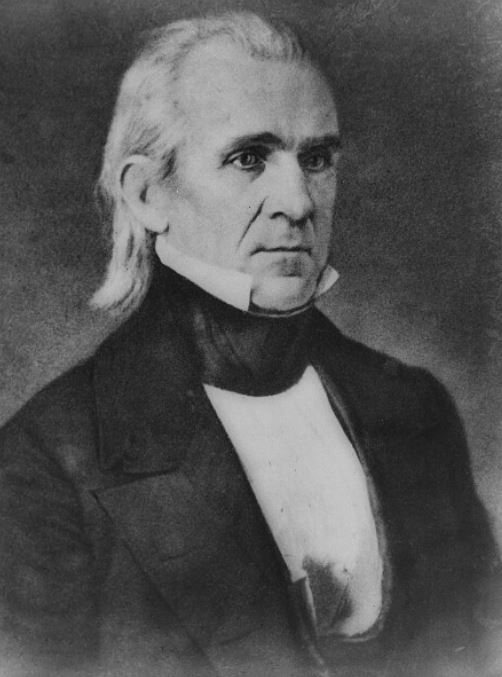

President James K. Polk stated that “American blood has been shed on American soil” and convinced Congress to declare war on Mexico in May 1846.

The ensuing conflict lasted just under two years. Despite being outnumbered and outmatched by the superior Mexican forces early on, the U.S. military was able to achieve a series of decisive victories.

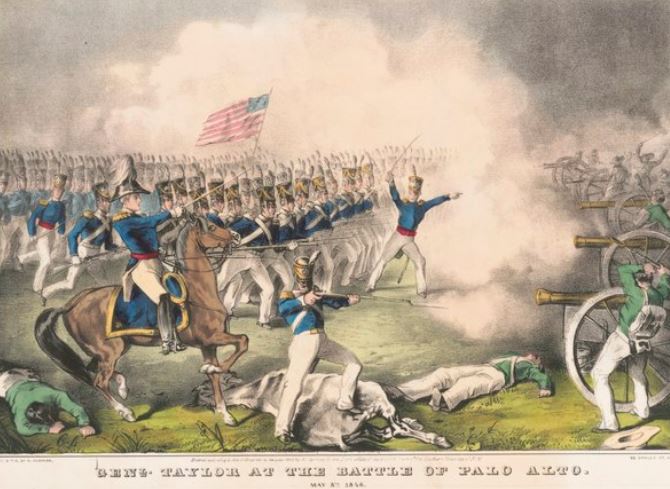

General Zachary Taylor defeated the Mexican forces at the battles of Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma in May 1846.

In September 1847, after a prolonged siege, U.S. forces under Winfield Scott captured Mexico City itself. Once in the Mexican capital, Scott’s troops forced the Mexican government to negotiate an end to hostilities.

Mexican Cession

The war officially ended in February 1848 with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

Under its terms, Mexico ceded nearly half its territory to the United States in what was known as the Mexican Cession.

The Mexican Cession comprised present-day California, Nevada, Utah, most of Arizona, and parts of Colorado, New Mexico and Wyoming. This amounted to over 525,000 square miles of land – an area roughly equal to the combination of France, Spain, Portugal, Germany and Switzerland.

In exchange for this massive land concession of over 500,000 square miles, the U.S. agreed to pay $15 million in compensation to Mexico and assume over $3 million in debts that the Mexican government owed to U.S. citizens.

The treaty was incredibly advantageous to the United States, nearly doubling its territorial size.

For the United States, acquiring such a vast stretch of western lands was a geopolitical prize beyond its wildest dreams just decades earlier. The Cession opened up the Southwest and West Coast for American emigration, commerce, natural resources and political integration into the union.

However, the Mexican Cession added new complexity to the issue of slavery that was already dividing the nation. The newly acquired lands reignited bitter debates over whether slavery would be permitted to expand into these western territories. The Wilmot Proviso was an unsuccessful effort to ban slavery from any lands taken from Mexico.

Northerners generally opposed expansion of slavery, while Southerners demanded their right to take enslaved people into new territories.

While a military victory for America, the Mexican-American War was highly controversial and cemented divisions over the issue of westward expansion of slavery into the new territories. This set the stage for further sectional conflict that eventually led to the Civil War just over a decade later.

2. Pre-war Tensions leading up to the Mexican-American War

Prior to the outbreak of the Mexican-American War, the issue of slavery’s expansion westward had already been sowing deep divisions between the North and South for decades.

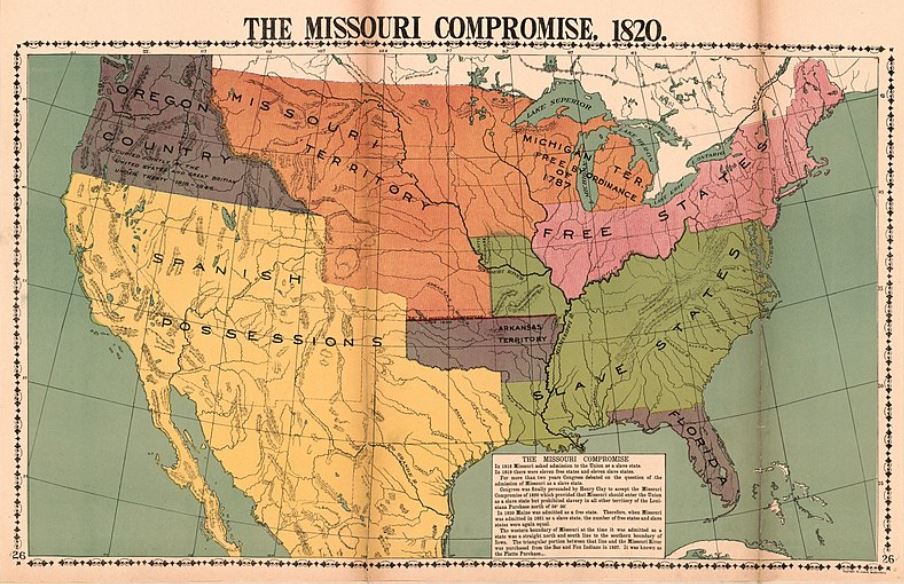

The Missouri Compromise of 1820 was an early attempt to maintain a balance between slave and free states as the nation grew. It admitted Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state, while decreeing that slavery would be prohibited north of the 36°30′ parallel in the remaining Louisiana Purchase lands.

However, this tenuous compromise began to fray as more western territories sought statehood.

Abolitionists in the North morally opposed to slavery on principle. They feared an imbalance that would allow the Southern slave states to maintain excessive power and influence in national politics.

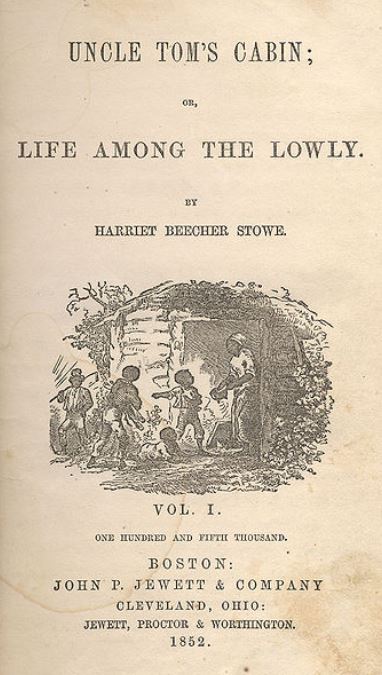

The publication of anti-slavery works like Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe in 1852 further inflamed Northern opposition to slavery’s expansion.

In the South, however, there were grave economic concerns over limits to the growth of slavery and the plantation system it supported.

The Southern economy had become deeply entrenched in and dependent on the cultivation of cash crops like cotton, tobacco, and sugarcane by enslaved labor. Any threats to the institution of slavery represented an existential danger to their agrarian economic model and way of life.

Beyond just the slavery issue, there were stark economic and industrial differences developing between the North and South that impacted their desires for western expansion.

- In the North, the economy was becoming industrialized with urban manufacturing centers, giving it interests in western trade routes and mining rather than cultivation of new farmlands.

- The South, meanwhile, sought to replicate its plantation agriculture model by extending into new western territories suitable for growing labor-intensive cash crops.

These competing expansionist interests, combined with the moral and economic controversies surrounding slavery, turned the acquisition of western lands from Mexico into a powder keg of sectional tensions.

3. The Road to Civil War

The Mexican-American War and its resulting Mexican Cession lands poured gasoline on the already smoldering fires of sectional conflict over slavery’s expansion.

In an effort to douse the crisis, Congress attempted to forge a new compromise in 1850. The Compromise of 1850 allowed California to be admitted as a free state while leaving the issue of slavery up to popular sovereignty in the remaining cession territories of Utah and New Mexico.

It also abolished the slave trade in Washington D.C. while enacting a tough new fugitive slave law.

However, rather than resolving the sectional divisions, the Compromise of 1850 merely delayed an even bigger confrontation.

Popular sovereignty invited further conflict, as the question remained whether the Mexican Cession lands would eventually become free or slave territories and states.

The Election of 1860 and Southern Secession

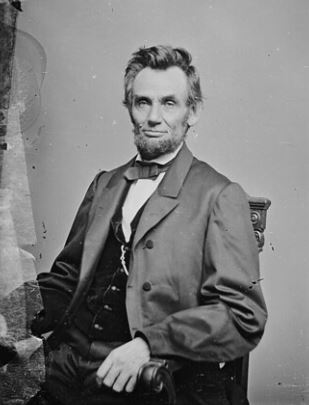

In the 1860 presidential election, the Republican Party candidate Abraham Lincoln secured victory while gaining no electoral votes from any of the Southern slave states.

Though Lincoln maintained he would not interfere with slavery where it already existed, his win was seen by many in the South as an existential threat to their economic system and way of life.

Within three months of Lincoln’s inauguration, seven Southern slave states had seceded from the United States and formed the breakaway Confederate States of America.

Both sides began raising armies as national leaders failed to resolve the crisis. After Confederate forces attacked Fort Sumter in South Carolina in April 1861, Lincoln called for troops to put down the rebellion, marking the official start of the Civil War.

Four more slave states joined the Confederacy, bringing the total to eleven states seceding over the threat to the institution of slavery posed by Lincoln’s election.

Texas Joins the Confederacy in 1861

February 1, 1861 proved to be a dark day in Texas history. On that day, delegates at the state’s Secession Convention in Austin voted overwhelmingly, 166 to 8, to secede from the United States of America.

Just one month later, in March 1861, Texas officially withdrew from the United States and became the 7th state to join the newly-formed Confederate States of America.

In doing so, they cast their lot with the breakaway Southern states in what would become the bloody American Civil War. For the next four years, from 1861 to 1865, Texas remained an active member of the Confederacy.

The state’s vast agricultural resources and manpower were key contributors to the Southern cause. Thousands of Texans took up arms and fought in major battles across the South. The state’s coastal areas also became strategic fronts, with Union naval forces seeking to blockade and seize control.

4. What if the Mexican-American War ended differently?

One could argue that if the Mexican-American War had never occurred or had a different outcome without massive territorial gains for the United States, the Civil War may have potentially been delayed or even avoided entirely.

Without the acquisition of the Mexican Cession lands, the contentious issue of whether to allow slavery’s expansion into those territories would have been moot.

Delaying the Conflict

The absence of this particular flashpoint may have allowed the Missouri Compromise line to persist for longer without being disrupted.

This could have postponed the sectional blow-up over the Kansas-Nebraska Act and events like “Bleeding Kansas” that tipped the nation into Civil War in 1861.

The powder keg of tensions may have had more time to defuse itself through other political resolutions before erupting into violence.

Deeper Underlying Tensions

However, it’s important to note that while pivotal, the Mexican Cession lands debate was not the sole contributing factor that led to the Civil War.

The economic differences between the industrialized North and slaveholding agricultural South had been intensifying for decades regardless of western expansion.

The rise of abolitionist fervor in the North also represented an existential threat to the Southern way of life centered on slavery.

Inevitable Clash?

So while avoiding the Mexican-American War may have delayed the Civil War’s timing, the fundamental conflicts and opposing moral, economic and political forces at play between North and South were perhaps too entrenched and irreconcilable to prevent conflict.

5. Final Thoughts on The Mexican-American War and the Civil War

The Mexican-American War, though not a direct spark itself, added explosive fuel to the simmering sectional Crisis over slavery’s westward expansion.

By igniting conflicts over the status of new western territories like the Mexican Cession, it heightened political polarization between the anti-slavery North and pro-slavery South.

Ultimately, the failure of compromises like the Kansas-Nebraska Act to resolve these tensions contributed significantly to the breakdown that culminated in the South’s secession and the Civil War’s outbreak in 1861.

However, the Mexican-American War reflected the underlying moral, economic, and political forces already entangling the nation in an intractable bind over slavery’s future.

Though not the sole factor, it emerged as an indispensable part of the complex tangle of issues pushing America towards its tragic intra-national conflict.

Further Reading

If you enjoyed this article, you may be interested to read more about the American Civil War events, or perhaps read about the Mexican-American War.