In 1836, Texas broke away from Mexico and declared itself an independent republic after winning the Texas Revolution.

But did Mexico simply accept this loss of territory and population? Or did it view Texas as a breakaway province that needed to be brought back under Mexican control? This lingering territorial dispute set the stage for years of tensions and military conflict between Mexico, Texas and the United States.

From rejecting Texas’s independence to launching armed invasions attempting to retake the territory by force, Mexico repeatedly tried to reverse Texas’s self-governance.

Read on to learn the fascinating history of Mexico’s struggle to regain Texas.

- 1. Texas Independence

- 2. Mexico's Response to Texas Independence

- 3. The Córdova Rebellion in 1838

- 4. The Texan Santa Fe Expedition in 1841

- 5. Texas Seeking International Recognition

- 6. Annexation of Texas into the United States

- 7. The Mexican-American War (1846-1848)

- 8. Mexico Abandons Military Efforts to Reclaim Texas After 1848 War

- Further Reading

1. Texas Independence

Texas originally belonged to Mexico, forming part of the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas. This vast territory had been under Spanish rule for centuries until Mexico itself won independence from Spain in 1821 after a decade of revolutionary war.

Just 15 years later, in 1835, settlers in Texas – many of them from the United States – revolted against the Mexican government.

Growing tensions over issues like immigration, religion, and centralized control under the Mexican federal republic boiled over into open conflict known as the Texas Revolution.

After a series of battles and sieges culminating in the decisive Battle of San Jacinto in 1836, the Texian revolutionary forces decisively defeated and captured Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna.

Following this major victory, Texas declared its complete independence from Mexico on March 2, 1836, and the Republic of Texas was officially established as a sovereign nation.

For the new government of Mexico, the loss of such a large portion of its national territory was nothing short of catastrophic. The detachment of Texas represented a huge blow in terms of land area, population, resources, tax revenues, and global standing for Mexico.

Many political and military leaders refused to accept the legitimacy of Texas’s independence and insisted it remained a breakaway province in rebellion.

Mexico’s stance set the stage for an incredibly tense and hostile relationship with its former territory for the next 9 years of Texas’s existence as an independent republic. The Mexican government flatly rejected any recognition of Texas’s sovereignty and maintained it had a rightful claim to bring Texas back under its control by force if necessary.

This refusal to relinquish Texas as a renegade part of Mexico laid the foundations for future military conflict.

2. Mexico’s Response to Texas Independence

Despite this major defeat at the Battle of San Jacinto in April 1836, where Mexican President/General Antonio López de Santa Anna was captured, Mexico refused to accept Texas independence.

The Mexican government continued intermittent military incursions and engagements against the Republic of Texas over the next nine years in an effort to weaken or reoccupy the breakaway state.

With Santa Anna as a prisoner, Mexico did not approve any treaties or promises he made. They maintained Texas remained a part of Mexico and simply could not constitutionally leave.

Anti-Texas hardliners argued Santa Anna had no authority to acknowledge Texas sovereignty or comply with excessive territorial demands.

However, internal political turmoil and bankrupt finances in Mexico prevented their government from marshaling overwhelming troop numbers for prolonged invasion and reconquest.

While neither Mexico nor the fledgling Texas republic had the resources for total, prolonged warfare, the two neighbors engaged in a cycle of frequent skirmishes, border raids, and armed instalments along their contested boundary over the next decade.

3. The Córdova Rebellion in 1838

The Córdova Rebellion, in 1838, was an uprising instigated in and around Nacogdoches, Texas by ethnic Tejano residents. The rebel leader, Alcalde (Mayor) Vicente Córdova, along with other Tejano politicians and landowners, wanted Texas to remain aligned with the liberal Mexican Constitution of 1824 that allowed for more regional autonomy.

As the Republic of Texas solidified its governance and legal systems, many of the Anglo-American settler majority pushed policies and laws that disenfranchised the native Tejano population who had historic land grants and rights under Mexican rule. This sparked the 1838 rebellion as Córdova and his followers rejected the Anglo-centric vision taking hold.

The Córdova forces aimed to overthrow the Republic of Texas government with hopes of rejoining Mexico, or at minimum securing respect for Tejano rights and customs.

However, the rebellion was swiftly crushed by Texian militia forces under President Sam Houston. Its leaders like Córdova were arrested, with several executed for treason against the republic.

The failed uprising deepened existing ethnic and cultural divides in Texas between the established Tejano families and communities versus more recently arrived Anglo settlers from the United States.

It marked a turning point where Anglo political and legal dominance became institutionalized, sidelining the influence of native Tejano people in the lands their ancestors had settled.

4. The Texan Santa Fe Expedition in 1841

The Texan Santa Fe Expedition of 1841 was an ambitious venture by the Republic of Texas aimed at establishing trade and political influence in the Mexican province of New Mexico.

It held the dual objectives of tapping into the lucrative Santa Fe Trail commercial network and annexing the eastern half of New Mexico territory for an expanded Republic of Texas.

The expedition was the brainchild of the 2nd Texas President Mirabeau B. Lamar, who harbored grand visions of transforming Texas into a continental power before increasing calls for annexation by the United States could take hold. In 1840, Lamar’s administration had already begun outreach efforts, sending commissioners to court New Mexico’s inclusion under Texas’s sphere.

Many Texans believed the predominantly Hispanic population of New Mexico, disenchanted with the Mexican government, would welcome joining the Republic. So in 1841, an expedition set out from Austin made up of around 320 men – a mix of merchants hoping to establish Santa Fe Trail trade routes, along with a sizeable military escort led by West Point graduate Hugh McLeod.

However, the expedition quickly ran into troubles on its nearly 1,000 mile journey. Poor planning and logistical supply issues plagued the group, who also faced sporadic raids from Native tribes. After getting lost without a guide, the expedition split into advance parties to find the way.

When they finally straggled into New Mexico months later, the Texans expected a warm welcome to start trade negotiations. Instead, they were surrounded by an intimidating force of 1,500 Mexican troops assembled by the provincial governor, Manuel Armijo.

Badly outnumbered and depleted from their grueling trek, the Texan expedition surrendered.

The captured Texans were then forced to endure a harsh 2,000 mile march to Mexico City, where they were imprisoned until diplomatic pressure from the U.S. finally secured their release in mid-1842.

The utter failure and humiliation of the Santa Fe Expedition proved a major political disaster for President Lamar and his expansionist agenda. This debacle is considered a pivotal factor turning popular opinion in Texas away from ambitions of remaining an independent republic.

5. Texas Seeking International Recognition

Though vying for international support, including efforts by the first Texas President Sam Houston to court European allies against Mexico, the small Republic lacked funds and arms to definitively defeat Mexico’s larger military forces in major pitched battles.

6. Annexation of Texas into the United States

Within Texas, sentiment grew for the republic to join the United States as a new state.

For many Texans, particularly recent arrivals from the United States, incorporation into the U.S. offered greater stability, security, and economic opportunity.

However, the proposed annexation of Texas was hugely controversial within the U.S. Congress and the nation.

Critics opposed adding more territory in which slavery would be permitted to expand. There were also concerns about inheriting the unresolved territorial conflicts and potential for renewed war with Mexico.

After heated national debates, Congress narrowly voted to annex Texas in 1845, making it the 28th U.S. state.

In response, Mexico severed diplomatic relations with the United States.

From Mexico’s perspective, the U.S. had incorporated land that rightfully belonged to Mexico. Tensions further escalated when the question arose of where exactly the Texas-Mexico border lay, which brings us to the origins of the Mexican-American War.

7. The Mexican-American War (1846-1848)

When the Republic of Texas was annexed and joined the United States in 1845, it reignited longstanding territorial disputes with Mexico over the Texas-Mexico border region.

This controversy over where the southwestern boundary between the two nations actually lay quickly escalated tensions to the breaking point.

The Mexican-American War: Origins

When Texas joined the U.S., it claimed borders extending to the Rio Grande river based on the territory of the former Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas that had encompassed Texas.

However, Mexico maintained the legitimate border was the Nueces River, leaving a large strip of land in between the two rivers as disputed contested ground.

Both the U.S. and Mexico accused the other of encroaching into this borderland area they insisted was rightfully theirs. Skirmishes and hostile encounters grew increasingly frequent as both sides deployed troops to defend their claimed boundaries.

The spark that finally ignited the Mexican-American War occurred in April 1846 along the Rio Grande near the modern-day cities of Brownsville and Matamoros. A patrol led by U.S. Captain Seth Thornton was attacked by Mexican cavalry, resulting in deaths on both sides in what became known as the Thornton Affair.

Whether Thornton’s patrol represented the initial incursion has remained hotly debated, but for both nations it was seen as an intolerable escalation of force justifying a military response. The already heightened tensions had become an open conflict that neither side could back down from any longer.

President James K. Polk’s administration used the Thornton incident to rally support for war.

When President Polk received reports of the Thornton Affair clash along the Rio Grande, combined with Mexico’s rejection of U.S. diplomatic envoy John Slidell, he believed this constituted sufficient justification for war. Polk declared to Congress that “American blood has been shed on American soil” and that Mexico had passed “the boundary of the United States” by invading U.S. territory.

This framing allowed Polk to rally Congressional support for a declaration of war against Mexico, which passed on May 13, 1846 after just hours of debate. The war declaration had strong backing from southern Democrats, though it faced opposition from some Whigs like Abraham Lincoln who challenged whether American blood was truly shed on American soil.

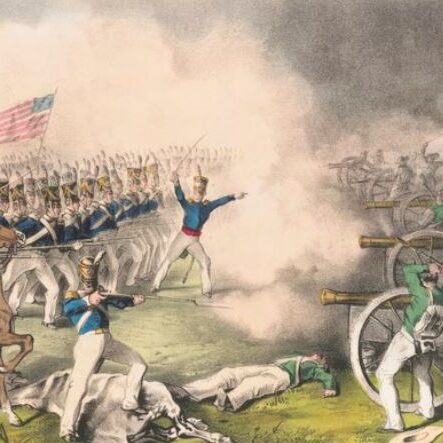

A War on Two Fronts

What followed was a bloody and bitter two-year conflict fought across Mexican territory from the Rio Grande to Mexico City itself.

The U.S. war strategy consisted of a dual invasion force – one army led by General Zachary Taylor pushing deep into northeastern Mexico, while a second expeditionary force under General Stephen Kearny seized New Mexico and California.

The U.S. forces held strategic advantages of greater manpower, experience, training, and resources. Despite acts of heroic resistance by Mexico’s army and citizen militias, they were gradually pushed back by the overwhelming U.S. military might.

Key U.S. victories included the battle of Buena Vista, the amphibious landings at Veracruz, and the brutal final campaigns to capture Mexico City.

After the Mexican capital fell in September 1847, the losses and staggering casualties compelled the Mexican government to negotiate peace.

War’s Outcome

In February 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed to end the hostilities. The terms forced Mexico to officially cede and recognize U.S. sovereignty over an enormous stretch of territory.

This included formalizing the annexation of Texas as a U.S. state within its claimed boundaries extending to the Rio Grande. But even more significantly, it extended American dominion all the way to the Pacific Ocean.

Encompassing nearly half of Mexico’s national territory, the lands ceded included all or part of the present day states of California, Nevada, Utah, most of Arizona, as well as portions of Colorado, New Mexico, and Wyoming.

The massive land concession represented a spectacular loss for Mexico after its failed efforts to reclaim or retain the breakaway province of Texas.

The Mexican Cession more than doubled the size of the United States overnight.

It fulfilled the nation’s long-held ambitions dating back to the Louisiana Purchase of establishing a coast-to-coast domain spanning the entire continent. For Mexico, however, it marked a catastrophic dismemberment of their young nation’s territorial integrity.

It was seen as an unforgivable act of aggression and national mutilation at the hands of an expansionist neighbor taking advantage of Mexico’s weakness and instability.

While the Mexican-American War ensured Texas’s permanent incorporation into the United States, the war’s consequences upended the geopolitical map of North America in ways that reverberated for generations after its conclusion in 1848.

The stroke of a pen formalized Mexico’s failure to regain Texas while stripping away even more of its national lands.

8. Mexico Abandons Military Efforts to Reclaim Texas After 1848 War

Mexico repeatedly attempted to retake Texas militarily after the territory declared independence in 1836. Major invasions by Mexico’s army in 1836 and 1846 failed. Frequent skirmishes and tensions persisted during the nine years of Texas’s existence as an independent republic.

However, after Texas joined the United States in 1845, Mexico permanently lost any reasonable prospect of regaining control of the territory through force of arms. The Mexican-American War sealed this fate, with Mexico forced to officially cede Texas and vast additional territories to the United States in 1848.

Mexico did not actively pursue large-scale military campaigns to reclaim Texas after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. This was because:

- Defeat and Exhaustion: Mexico suffered a significant military defeat in the Mexican-American War. The country was financially drained and politically unstable, making it difficult to launch another major war.

- US Military Power: The United States emerged from the war as a stronger regional power. Mexico likely recognized the futility of attempting to take Texas back by force.

- International Recognition: The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was recognized by the international community, further legitimizing Texas as part of the US.

Mexico eventually focused on internal development and establishing peaceful relations with the US.

Further Reading

If you enjoyed this article, you may be interested to read more about the American Civil War events, or perhaps read about the Mexican-American War or Texas.