When Cnut (or Canute) seized the English throne in 1016 after years of brutal Viking invasions, few could have predicted his remarkable change.

The young Danish conqueror, who began his career leading ruthless raids along England’s coasts, would ultimately reinvent himself as one of Europe’s most sophisticated Christian rulers.

This dramatic evolution was no accident.

Cnut recognized early that sustaining power required more than military dominance—it demanded political savvy, religious legitimacy, and imperial vision. Over his nineteen-year reign (1016-1035), he carefully crafted an image that balanced his Viking heritage with the expectations of Christian kingship. By the time of his death, he had become not just a king, but an emperor in all but name—his influence stretching from the fjords of Norway to the shores of Wessex.

This article explores Cnut’s extraordinary political journey, examining how a feared Scandinavian warlord transformed himself into a model of pious Christian rulership.

1. Architect of an Empire: Governing the North Sea Realm

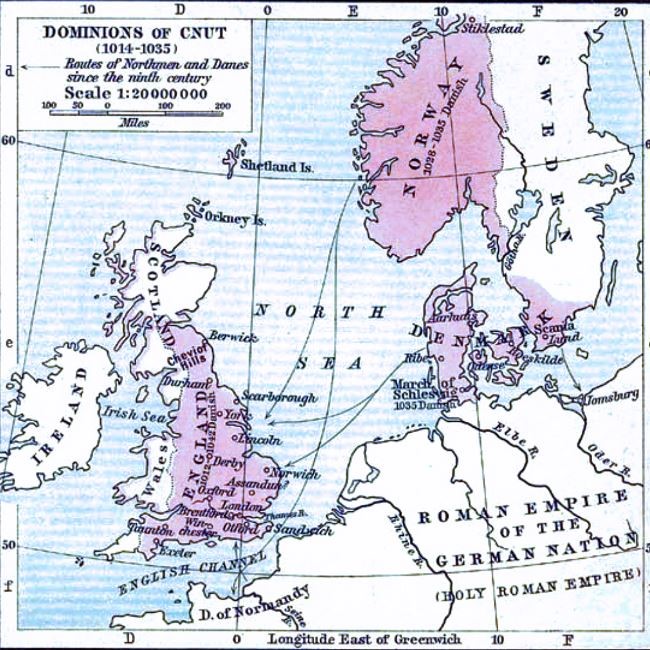

At its height around 1030, Cnut’s empire encompassed:

- England (conquered 1016)

- Denmark (inherited 1018)

- Norway (subdued 1028)

- Influence over parts of Sweden and the Norse settlements in Ireland and Scotland

This territorial expanse made him the most powerful ruler in northern Europe since Charlemagne two centuries earlier. But unlike the Frankish emperor who ruled through centralized administration, Cnut’s empire was a looser, more pragmatic coalition of territories—each requiring different governance approaches.

The Art of Delegated Rule

Cnut’s genius lay in recognizing that different regions demanded different strategies:

In England:

- Retained the existing Anglo-Saxon administrative system

- Appointed key English nobles like Godwin of Wessex to powerful earldoms

- Married Emma of Normandy to connect himself to the old West Saxon dynasty

In Scandinavia:

- Ruled Denmark directly as hereditary king

- Installed his sister Estrid’s family as local governors

- Appointed his first wife Ælfgifu and their son Svein as regents in Norway

This flexible approach allowed him to maintain control without constant military presence—a necessity given the vast distances between his territories.

Cnut maintained power through an intricate system of rewards and relationships:

- Lavish gifts of land and treasure to key supporters

- Strategic marriages for his family members

- Annual payments (Danegeld) to Scandinavian forces to prevent rebellions

His court became a melting pot of cultures—Anglo-Saxon thegns serving alongside Danish huscarls, with Latin-speaking churchmen advising them all.

2. The Piety of Power: Cnut’s Christian Kingship

From Pagan Raider to Church Patron

Cnut’s conversion wasn’t merely personal—it was political theater of the highest order. By the 1020s, he had become the Church’s most generous patron:

Major Religious Contributions:

- Rebuilt the monastery at Assandun (site of his decisive 1016 victory)

- Endowed Wilton Abbey where his daughter became a nun

- Donated lavish gifts to Canterbury Cathedral and Winchester’s Old Minster

These weren’t random acts of devotion. Each donation strengthened alliances with powerful bishops while broadcasting his Christian credentials across Europe.

Lawgiving as Legitimacy

Cnut’s law codes, drafted with Archbishop Wulfstan of York, reveal his political acumen:

- Protected Church rights and properties

- Punished pagan practices (while tolerating some Norse customs)

- Positioned the king as God’s appointed guardian of justice

The laws cleverly blended Anglo-Saxon traditions with royal authority, presenting Cnut not as a foreign conqueror but as England’s rightful Christian ruler.

The Legend of the Tide

The famous (likely apocryphal) story of Cnut commanding the tides encapsulates his image-making:

- Allegedly had his throne placed on the shore to demonstrate even kings couldn’t control nature

- Publicly acknowledged God’s supreme authority

- Reinforced that his power came from divine sanction

Whether factual or not, the tale spread widely, cementing his reputation as a humble Christian monarch.

3. Coronation in Rome: The Masterstroke (1027)

Cnut’s journey to Rome in 1027 wasn’t just spiritual—it was the culmination of his political strategy. His attendance at Conrad II’s coronation as Holy Roman Emperor placed him at the center of Christendom’s power structures.

Contemporary accounts highlight his extraordinary reception:

- Granted a place of honor beside the new emperor

- Negotiated reduced tolls for English pilgrims and merchants

- Secured promises of protection for English churches

These achievements weren’t merely symbolic—they brought tangible benefits to his kingdom while elevating his international standing.

Cnut also consciously modeled himself after legendary Christian rulers:

- Charlemagne: Like the Frankish emperor, he united diverse peoples under Christian rule

- Constantine: Presented himself as a unifier of church and state

- King David: His law codes referenced biblical kingship ideals

His letter home from Rome (preserved in chronicles) reads like an imperial proclamation, addressing his subjects as both king and protector of Christendom.

Final Thoughts: The Legacy of a Viking Emperor

Cnut’s death in 1035 marked the beginning of his empire’s fragmentation, but his political vision endured. He had demonstrated that:

- Conquest required consolidation

- Power demanded legitimacy

- Rule necessitated representation

Later medieval kings would follow his blueprint—from William the Conqueror’s use of Church support to Henry II’s legal reforms. Even his failures (like the unpopular Norwegian regency) offered lessons in the limits of cross-cultural rule.

Ultimately, Cnut’s story transcends the simplistic “Viking” stereotype. He was a bridge between eras—the last great North Sea warlord and the first truly European-style monarch of England.

His reign proves that in the medieval world, the most successful conquerors weren’t those who took kingdoms by force, but those who knew how to make them endure.

Final Reflection: Eight centuries later, Napoleon would famously state that “a throne is just a bench covered in velvet.” Cnut, in his way, had already proven this truth—showing that real power lay not in the seat itself, but in the ability to convince others it was yours by right.

Further Reading

If you enjoyed this article, you may enjoy these:

- Queens and Power: The Women Behind King Cnut’s Empire

- Cnut the Conqueror: How a Viking Became King of England

- Blood on St. Brice’s Day: Æthelred’s Viking Massacre

- Emma of Normandy: Queen, Pawn, and Power Broker

- The Fear of the Year 1000: Apocalyptic Anxieties

- Tribute or Treason? Æthelred’s Gamble with the Vikings

- The Anglo-Saxon State: How England Built Europe’s Most Centralized Medieval Government

- Kings and Queens of England Ranked from Worst to Best

- How did Charlemagne improve the lives of people in Europe?

- Why was the crowning of Charlemagne so important?