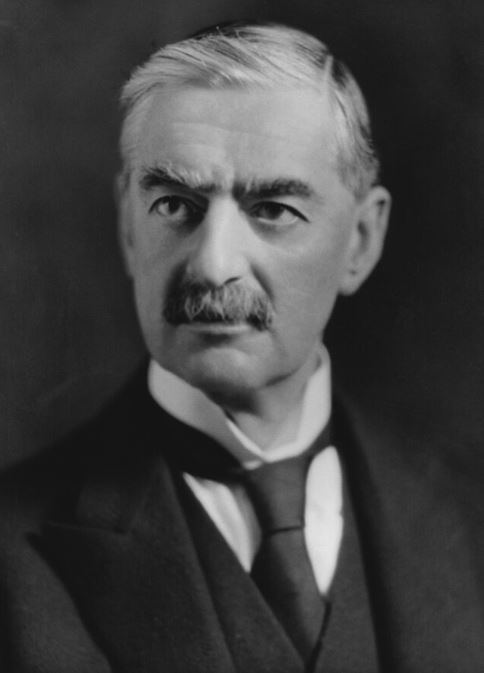

The policy of appeasement is one of the most debated strategies in modern history. Neville Chamberlain, the British Prime Minister who championed it, is often remembered as a naive leader who failed to stand up to Hitler.

But was appeasement really a cowardly mistake, or was it a calculated gamble to buy time and avoid a premature war?

This article explores the logic behind appeasement, its consequences, and the tantalizing “what if” scenarios that could have changed the course of history.

The Context of Appeasement

After the devastation of World War I, Europe was desperate to avoid another conflict. The memory of trenches, gas attacks, and millions of dead haunted the public.

In Britain, the desire for peace was overwhelming. Politicians knew that any move toward war would be deeply unpopular.

Economically, Britain was still recovering from the Great Depression. The country couldn’t afford to pour unsustainable amounts of money into rearmament.

Chamberlain, a pragmatic leader, believed in balancing the budget while gradually building up military strength.

But the world was changing.

Germany, under Hitler, was rearming at an alarming rate.

Italy, led by Mussolini, was expanding its influence in the Mediterranean.

Japan, once an ally, was becoming a threat in the Far East.

Britain faced the daunting prospect of fighting a three-front war. The Chiefs of Staff warned that Britain couldn’t defeat all three powers simultaneously. Appeasement, they argued, was a way to buy time and focus resources on the most immediate threat: Germany.

Chamberlain’s Strategy

Neville Chamberlain was not naive. He knew Adolf Hitler was dangerous. But he also knew that Britain was not ready for war.

In 1938, the British military was underfunded and outdated. The Royal Air Force (RAF) was still flying biplanes, relics of an earlier era, while the army was small and poorly equipped. The navy, though still formidable, was stretched thin across the globe, tasked with defending an empire that spanned continents.

Chamberlain’s strategy of appeasement was not born out of weakness or ignorance. It was a calculated decision to delay war while Britain rearmed.

The Munich Agreement of 1938, which allowed Hitler to annex the Sudetenland—a region of Czechoslovakia with a large ethnic German population—was the centerpiece of this strategy. Chamberlain hoped that by giving Hitler what he wanted, he could avoid a larger conflict.

Public opinion strongly supported this approach. Most Britons saw Czechoslovakia as a “faraway country” they knew little about. The idea of going to war over a distant land seemed absurd to many.

Chamberlain’s famous declaration of “peace for our time” after the Munich Agreement was met with widespread relief. For a brief moment, it seemed that war had been averted.

But behind the scenes, Chamberlain was far from complacent.

He was acutely aware of Britain’s military shortcomings and was determined to address them. He accelerated the production of modern aircraft, such as the Hawker Hurricane and the Supermarine Spitfire, which would later play a crucial role in the Battle of Britain. Defense spending was increased, and efforts were made to modernize the army and navy.

Chamberlain’s goal was to negotiate from a position of strength, not weakness.

He believed that if Britain could build up its military capabilities, it could deter Hitler from further aggression. The Munich Agreement was not a surrender; it was a strategic pause, a way to buy time for Britain to prepare for the inevitable conflict.

Chamberlain understood that war might still come. But he hoped that by delaying it, Britain would be better prepared to face the challenge. He was not blind to Hitler’s ambitions, but he believed that a combination of diplomacy and rearmament could prevent a catastrophic war.

However, the strategy of appeasement had its critics.

Winston Churchill, then a backbench MP, was one of the most vocal opponents. He argued that Hitler could not be trusted and that every concession would only embolden him. Churchill believed that a firm stand in 1938 could have deterred Hitler and prevented the war.

Chamberlain’s approach was not without merit. By 1939, Britain’s military capabilities had significantly improved. The RAF had modern aircraft, and the army was better equipped. But the failure of the Munich Agreement to secure lasting peace ultimately tarnished Chamberlain’s legacy.

In hindsight, Chamberlain’s strategy of appeasement was a pragmatic response to an impossible situation. He faced a hostile and unpredictable dictator, a public deeply opposed to war, and a military that was not yet ready to fight. While his efforts to avoid conflict ultimately failed, they bought Britain valuable time to prepare for the challenges ahead.

Chamberlain’s story is a reminder of the difficult choices leaders must make in times of crisis.

The Failure of Appeasement

The Munich Agreement of September 1938 was supposed to secure “peace for our time.” Neville Chamberlain, the British Prime Minister, had negotiated with Adolf Hitler to allow Germany to annex the Sudetenland, a region of Czechoslovakia with a large ethnic German population.

In return, Hitler promised that this would be his last territorial demand in Europe. For a brief moment, it seemed that war had been averted. But the illusion of peace was short-lived.

By March 1939, Hitler had broken his promise.

German troops marched into the rest of Czechoslovakia, annexing the entire country. This blatant act of aggression shattered the illusion that Hitler could be appeased. The British public, which had initially celebrated the Munich Agreement, was now outraged. Even Chamberlain, who had once believed in the possibility of a peaceful settlement, realized that Hitler’s ambitions were limitless.

The annexation of Czechoslovakia was a turning point.

It exposed the futility of appeasement and marked the end of any hope that Hitler could be reasoned with. The British government, under pressure from public opinion, shifted its stance. No longer would concessions be made to Hitler. The policy of appeasement, which had been designed to prevent war, had failed to achieve its goal.

The failure of appeasement was further underscored by the events of Kristallnacht, the violent pogrom against Jews in November 1938. Over the course of two days, Nazi paramilitaries and civilians destroyed Jewish homes, businesses, and synagogues across Germany and Austria. The images of shattered glass, burning synagogues, and brutalized civilians shocked the world. It became clear that Hitler’s regime was not just a threat to peace but a moral abomination.

Kristallnacht was a stark reminder of the true nature of the Nazi regime.

It was not merely an aggressive power seeking territorial expansion; it was a brutal dictatorship committed to the persecution and destruction of entire groups of people.

The international community, which had largely turned a blind eye to Hitler’s earlier actions, could no longer ignore the reality of Nazi Germany.

In response to these developments, Britain and France issued a guarantee to Poland in March 1939, promising to defend it against German aggression. This marked the end of appeasement.

The guarantee was a clear signal that further expansion by Hitler would not be tolerated. It was a dramatic shift in policy, driven by the realization that Hitler could not be trusted and that his ambitions posed a direct threat to the balance of power in Europe.

When Hitler invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, Britain and France had no choice but to act.

On September 3, they declared war on Germany, marking the beginning of World War II. The policy of appeasement had failed, and the world was plunged into another global conflict.

The failure of appeasement has been the subject of intense debate among historians. Some argue that Chamberlain’s strategy bought Britain valuable time to rearm and prepare for war. By 1939, the Royal Air Force had modern aircraft like the Spitfire and Hurricane, and the British military was better equipped than it had been in 1938. Others, however, contend that appeasement only emboldened Hitler, allowing him to grow stronger and more aggressive.

One of the most significant criticisms of appeasement is that it undermined the credibility of Britain and France as defenders of international order.

By repeatedly conceding to Hitler’s demands, the Western powers sent a message that aggression would be rewarded. This not only strengthened Hitler’s position but also weakened the resolve of other nations to resist Nazi expansion.

The annexation of Czechoslovakia also had strategic consequences.

The Czechs had a well-equipped army and strong fortifications in the Sudetenland. By allowing Hitler to take the region without a fight, Britain and France lost a potential ally and handed Germany valuable resources, including the Skoda Works, one of Europe’s largest arms manufacturers.

In hindsight, the failure of appeasement serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of underestimating an aggressive adversary. Chamberlain’s belief that Hitler could be reasoned with was ultimately proven wrong. Hitler’s ambitions were not limited to the Sudetenland or even Czechoslovakia; they extended to the domination of Europe and beyond. The consequences of that failure would be felt for years to come, as the world was plunged into the deadliest conflict in human history.

What If The Allies Declared War In 1938 Over Czechoslovakia?

The Munich Agreement of 1938 is often seen as the defining moment of appeasement, a failed attempt to avoid war by conceding to Hitler’s demands. But what if Britain and France had taken a different path? What if they had stood firm in 1938 and declared war over Czechoslovakia?

This “what if” scenario is one of the most fascinating in history, offering a glimpse into how different decisions might have changed the course of events.

The Oster Conspiracy: Internal German Opposition to Hitler

One of the most intriguing possibilities is the potential for internal German opposition to overthrow Hitler if the Allies had taken a strong stance in 1938.

At the time, there was significant discontent within the German military and intelligence services. Many high-ranking officers, including General Ludwig Beck and Colonel Hans Oster, were deeply concerned about Hitler’s aggressive policies. They believed that a war over Czechoslovakia would be disastrous for Germany and were prepared to act if the Allies stood firm.

The Oster Conspiracy, as it came to be known, was a plot to overthrow Hitler if he pushed for war. The conspirators believed that a strong Allied response would provide the impetus for a coup. They had even drafted plans to arrest Hitler and other Nazi leaders, dismantle the regime, and establish a new government that would seek peace with the Allies.

If Britain and France had declared war in 1938, the conspirators might have acted. Hitler could have been assassinated, and the Nazi regime might have collapsed.

The horrors of World War II and the Holocaust might have been avoided.

This alternate history raises profound questions about the role of external pressure in shaping internal political dynamics.

However, the success of the Oster Conspiracy was far from guaranteed.

The German military was deeply divided, and many officers remained loyal to Hitler. The conspirators also lacked a clear plan for what would come after Hitler’s removal. Even if the coup had succeeded, it is unclear whether the new government would have been able to maintain control or negotiate a lasting peace.

Military Realities: Could Czechoslovakia Have Resisted?

Another key question is whether Czechoslovakia could have resisted a German invasion with Allied support.

The Czechs had a well-equipped army and strong fortifications in the Sudetenland, a mountainous region that provided natural defenses. The Czech military was also supported by a robust arms industry, including the Skoda Works, one of Europe’s largest arms manufacturers.

With Allied support, Czechoslovakia might have been able to hold out against Germany.

The French army, though reluctant to move beyond the Maginot Line, could have pressured Germany by threatening to invade the Rhineland.

The British, while unprepared for a large-scale ground war, could have provided air support and naval blockades to disrupt German supply lines.

However, the military realities of 1938 were far from ideal.

Britain’s army was small and poorly equipped, with only two deployable divisions. The Royal Air Force (RAF) was still transitioning from biplanes to modern aircraft like the Spitfire and Hurricane.

France, while possessing a large army, was plagued by political instability and a defensive mindset. The French high command was reluctant to take the offensive, preferring to rely on the Maginot Line for protection.

The Luftwaffe, though overestimated in its capabilities, still posed a significant threat. German air power had been demonstrated during the Spanish Civil War, and the fear of bombing raids loomed large in the minds of British and French leaders.

The joint planning committee predicted that Britain would suffer 150,000 casualties from bombing in the first week of the war alone.

In this context, a war in 1938 would have been a high-stakes gamble.

While Czechoslovakia might have been able to resist for a time, the outcome would have depended on the willingness of Britain and France to commit fully to the conflict.

The Rhineland Factor: Pressuring Germany

One of the most underappreciated aspects of this “what if” scenario is the potential for France and Britain to pressure Germany by moving into the Rhineland.

The Rhineland, a demilitarized zone under the Treaty of Versailles, was a strategically vital region for Germany. If Allied forces had occupied the Rhineland, they could have threatened Germany’s industrial heartland and disrupted its war effort.

The German economy in 1938 was fragile, and the military was not yet ready for a prolonged conflict.

Hitler’s rearmament program had strained Germany’s resources, and the country was facing a shortage of raw materials and foreign currency.

An Allied occupation of the Rhineland could have forced Hitler to divert resources from other fronts, weakening his ability to wage war.

However, the French high command was deeply reluctant to take the offensive. The memory of World War I, in which France had suffered devastating losses, loomed large. The French preferred to rely on the Maginot Line, rather than risk an invasion of the Rhineland.

Long-Term Implications: Preventing the Holocaust and Reshaping Europe

One of the most profound questions raised by this “what if” scenario is whether an early war could have prevented the Holocaust.

If Hitler had been overthrown or defeated in 1938, the Nazi regime might have collapsed before it could implement its genocidal policies. The millions of lives lost in the Holocaust might have been saved, and the course of history dramatically altered.

An early war could also have reshaped the balance of power in Europe.

Without the Nazi regime, Germany might have returned to a more moderate government, reducing the threat of future conflicts. The Soviet Union, which later emerged as a superpower after World War II, might have remained isolated and weakened.

However, the long-term implications are not entirely positive.

An early war could have led to a prolonged stalemate, with devastating consequences for Europe. The economic and human cost of a prolonged conflict might have been even greater than the actual war that followed.

Counterfactual Outcomes: A Shorter War or a Prolonged Stalemate?

The potential outcomes of an early war in 1938 are complex and multifaceted.

On one hand, a swift Allied victory could have led to a shorter, less devastating war. The Nazi regime, still in its early stages, might have been easier to dismantle than the entrenched dictatorship it became by 1939.

On the other hand, a war in 1938 could have resulted in a prolonged stalemate. Britain and France were not yet fully prepared for a large-scale conflict, and their military capabilities were limited. The German army, though not as strong as it would become, was still a formidable force. A prolonged conflict could have drained the resources of all parties, leading to widespread suffering and instability.

The role of the Soviet Union adds another layer of complexity. If Britain and France had gone to war in 1938, Stalin might have seized the opportunity to expand Soviet influence in Eastern Europe. The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, which divided Poland between Germany and the Soviet Union, might never have been signed. Instead, the Soviet Union could have emerged as a dominant power in the region, reshaping the post-war order in unpredictable ways.

Final Thoughts: Neville Chamberlain’s Legacy

Chamberlain’s policy of appeasement is often seen as a failure. But was it?

Chamberlain wasn’t a naive fool. He was a pragmatic leader making the best of a bad situation. His strategy bought time for Britain to rearm and prepare for war. By 1939, the Royal Air Force had modern aircraft like the Spitfire and Hurricane, and Britain was better prepared to face Germany.

But Chamberlain’s fatal flaw was his belief that Hitler could be appeased. He underestimated the Nazi leader’s ambitions and the brutality of his regime.

Appeasement was a calculated gamble, not a cowardly mistake. Chamberlain’s strategy bought time for Britain to rearm, but it failed to stop Hitler.

The debate over appeasement is still relevant today. How should democracies deal with aggressive regimes? Is it better to negotiate or take a firm stand?

The “what if” scenarios are also tantalizing. Could a stronger stance in 1938 have changed the course of history? We’ll never know for sure. But one thing is clear: the lessons of appeasement continue to shape how we think about war, peace, and the responsibilities of leadership.

Further Reading

If you enjoyed this article about appeasement, you may be interested to read more about other wars in history, such as the American Civil War and World War 1.

Here are some specific World War 2 articles you may also enjoy:

- Why did Germany go to war in World War 2?

- Should Germany Have Fought the Battle of Kursk?

- What If Germany Had Won the Battle of Kursk?

- Who were the Ghost Division of World War 2?

- What were the German Special Forces called in World War 2?

- What Side was Ireland on in World War 2?

- Who were the Main Dictators of World War 2?

- Why did France lose so easily in World War 2?

You may also enjoy these articles about the World Wars: