The Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) was a monumental clash that reverberated across continents, reshaping the global balance of power in the 18th century.

Often called the first “world war,” this epic conflict spanned Europe, North America, India, the Caribbean, and Africa, drawing in nearly every major power of the era.

The stakes were immense—control of vast colonial empires, dominance over lucrative trade routes, and the future of nations were all on the line. This war not only pitted rival empires against each other but also sowed the seeds for revolutionary changes that would redefine the political and economic landscape for decades to come.

Read on to fine out how the Seven Years’ War unravelled.

1. The Origins of the Seven Years’ War

The origins of the Seven Years’ War lie in the ongoing struggle between European powers for dominance, particularly between Britain and France.

These two colonial superpowers had a long-standing rivalry fueled by competition over colonial territories, lucrative trade routes, and political influence. Their clashes in North America, the Caribbean, Africa, and Asia reflected a broader global contest for empire and wealth.

The stakes were immense: controlling strategic regions could tilt the balance of power in favor of one nation, providing unparalleled economic and military advantages.

This conflict was not limited to Britain and France.

Colonial Rivalries in North America

Tensions in North America escalated dramatically during the mid-18th century as British colonists pushed westward into the Ohio Valley.

This fertile and strategically significant region was claimed by both Britain and France, and its control was vital for trade, settlement, and influence over Native American allies.

The Ohio Valley’s importance stemmed from its position as a gateway between the eastern seaboard colonies and the interior of the continent.

For the French, it was also a critical link connecting their Canadian territories with Louisiana.

The friction between British settlers and French forces reached a boiling point in 1754.

That year, Virginia Governor Robert Dinwiddie dispatched a young militia officer, George Washington, to demand the withdrawal of French troops from the area. The French refusal led to a skirmish at Fort Necessity, where Washington’s forces were ultimately defeated.

Although a small engagement, it marked the beginning of open hostilities in North America and foreshadowed the larger conflict to come.

France quickly reinforced its positions in the Ohio Valley, constructing a series of forts, including the formidable Fort Duquesne at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers.

In response, Britain organized military expeditions to assert its claims, but early campaigns met with failure. The most notable was General Edward Braddock’s disastrous attempt to capture Fort Duquesne in 1755, which ended in a devastating ambush and his death. These setbacks underscored the challenges Britain faced in penetrating French-held territories.

At the same time, both Britain and France worked to secure alliances with Native American tribes. The French generally had more success in this regard, as their fur trading economy fostered closer ties with indigenous communities. However, the British began to turn the tide by leveraging their superior resources and promises of protection.

The conflict in North America gradually drew in British and French regular forces, transforming it into a theater of the Seven Years’ War. By 1756, this local struggle over the Ohio Valley had merged with the broader global conflict. The colonial rivalries that had simmered for years now erupted into a full-scale war, with North America serving as one of its most critical battlegrounds.

Prussia’s Position in Europe

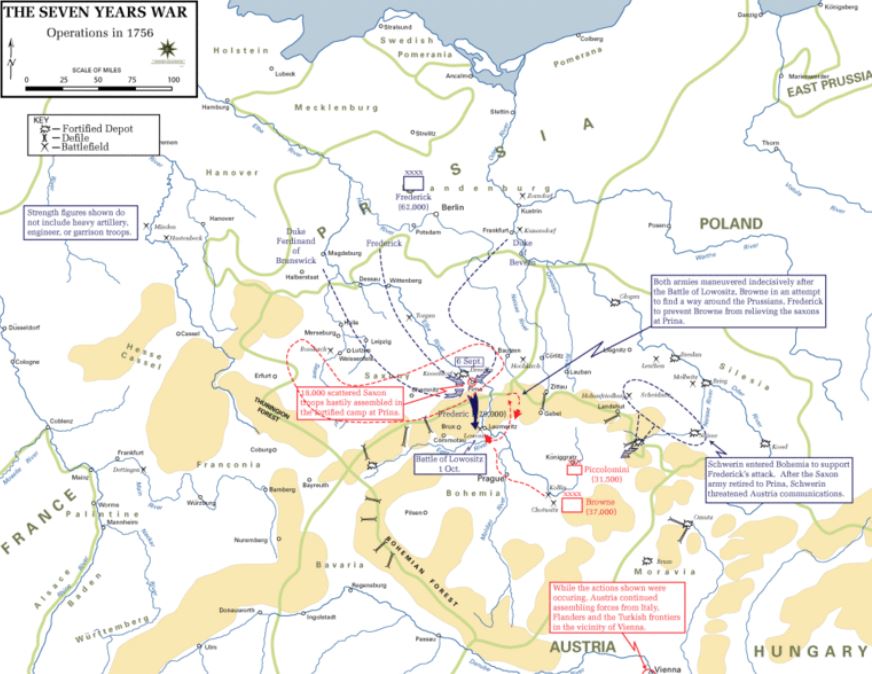

In Europe, the origins of the Seven Years’ War can be traced to the simmering tensions between Austria and Prussia.

These tensions were primarily rooted in Austria’s loss of Silesia to Prussia during the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748).

Silesia, a wealthy and strategically important region, had been a prized possession of the Austrian Habsburgs, and its loss to Frederick the Great of Prussia was a significant blow to Austrian prestige and influence. The Austrian Empress Maria Theresa was determined to reclaim Silesia and restore her country’s territorial integrity.

To achieve this goal, Austria sought to isolate Prussia diplomatically.

This effort culminated in the Diplomatic Revolution of 1756, an unprecedented realignment of traditional alliances. Austria formed a coalition with France, a former adversary, as well as Russia and Sweden. This coalition aimed to contain Prussia’s rising power and dismantle its territorial gains.

For Austria, France, and Russia, Prussia’s growing influence under Frederick the Great posed a significant threat to the balance of power in Europe.

Sweden, though less powerful, joined the coalition due to its longstanding rivalry with Prussia in the Baltic region.

Prussia, on the other hand, found an ally in Britain, which was seeking to counter French influence.

The Anglo-Prussian alliance was primarily a marriage of convenience, driven by mutual interests rather than shared ideologies. Britain provided financial and naval support to Prussia, while Prussia’s formidable land forces served as a counterweight to the coalition arrayed against them.

The war in Europe quickly became a test of Prussia’s military prowess and Frederick the Great’s strategic genius. Facing enemies on multiple fronts, Frederick adopted a strategy of rapid, decisive action.

He launched preemptive strikes against Saxony and Bohemia, aiming to disrupt the coalition’s plans before they could fully mobilize.

Despite being heavily outnumbered, Prussia’s disciplined armies and Frederick’s tactical brilliance enabled them to achieve remarkable victories. However, the war also brought immense challenges, with Prussia’s survival often hanging by a thread due to the sheer size and resources of its adversaries.

Prussia’s position in Europe during the Seven Years’ War thus exemplifies a precarious balance of bold leadership, strategic alliances, and relentless determination in the face of overwhelming odds.

2. Early Stages of the War

Frederick the Great’s Triumphs

Frederick the Great of Prussia emerged as one of the most remarkable military strategists of the Seven Years’ War, demonstrating unparalleled skill in the face of adversity.

Surrounded by enemies on nearly every side, Prussia found itself in a precarious position, outnumbered and outgunned by the coalition of Austria, France, Russia, and Sweden. Despite these challenges, Frederick relied on his keen strategic mind, superior troop discipline, and innovative tactics to defy expectations.

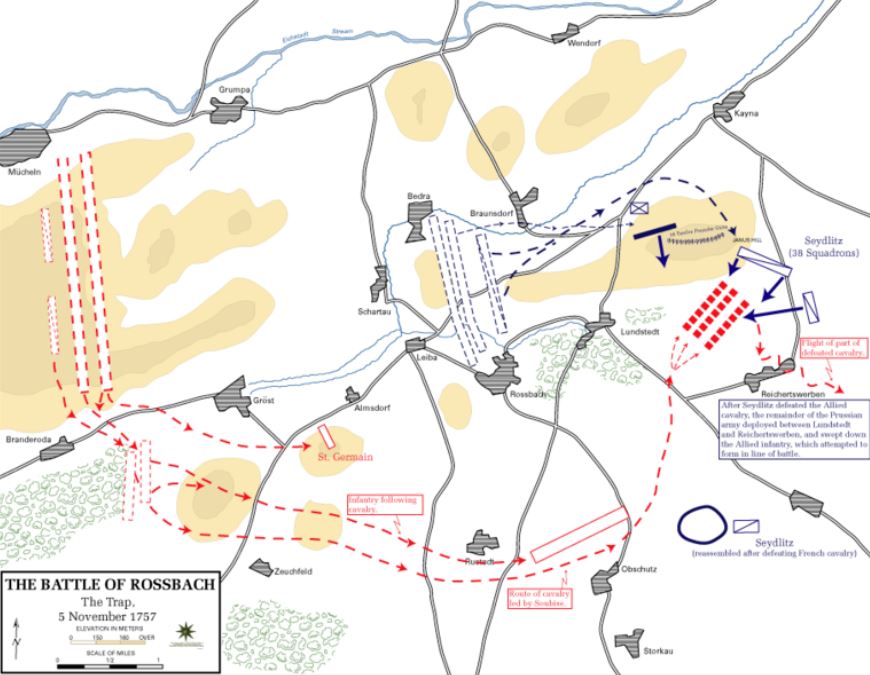

One of Frederick’s most celebrated victories occurred on November 5, 1757, at the Battle of Rossbach.

Facing a combined force of French and Holy Roman Empire troops that vastly outnumbered his own, Frederick deployed a daring strategy involving feigned retreats and rapid redeployment.

His 22,000 troops decisively defeated the 41,000-strong enemy force, inflicting heavy casualties while losing only a fraction of his own men. The victory at Rossbach shattered the myth of French invincibility and elevated Frederick’s reputation across Europe.

Barely a month later, Frederick achieved another stunning triumph at the Battle of Leuthen on December 5, 1757.

Facing the Austrian army, which was more than twice the size of his own, Frederick employed a series of bold flanking maneuvers.

His meticulous planning and the disciplined execution by his troops led to a resounding victory, securing Silesia for Prussia and further cementing his military legacy. These early successes not only boosted Prussian morale but also secured critical breathing room for the beleaguered state.

Conflict Expands to India

The Seven Years’ War was not confined to Europe; its global dimension was vividly demonstrated in India, where the British and French empires vied for dominance.

The struggle for control over the Indian subcontinent was primarily waged through their respective trading companies—the British East India Company and the French East India Company.

These entities, while ostensibly commercial organizations, maintained private armies and engaged in open warfare to secure territorial and economic supremacy.

The turning point in India came with the Battle of Plassey on June 23, 1757.

British forces, led by the ambitious and resourceful Lord Robert Clive, faced the Nawab of Bengal, Siraj-ud-Daulah, who was supported by French advisors and allies.

Clive’s army, though numerically inferior, leveraged superior tactics, local alliances, and the defection of key Bengali commanders to secure a decisive victory. The British victory at Plassey marked a seismic shift in power, enabling the East India Company to establish a dominant position in Bengal, one of the wealthiest provinces of India.

Beyond the immediate military success, the Battle of Plassey had profound long-term consequences.

It marked the beginning of British colonial dominance in India, with the East India Company gaining control over vast resources and territories.

French influence in the region waned significantly, as their limited victories were overshadowed by British gains. The outcome in India also had ripple effects on the broader conflict, as the wealth and resources acquired from Bengal bolstered Britain’s war effort on other fronts.

The Broader Implications of Early Victories

The early stages of the Seven Years’ War set the tone for the protracted conflict.

Frederick the Great’s victories in Europe demonstrated that Prussia was not a state to be easily crushed, despite its apparent vulnerabilities. His ability to outmaneuver larger and better-equipped armies became a critical factor in maintaining the balance of power in central Europe.

Meanwhile, British triumphs in India underscored the war’s truly global nature and foreshadowed the emergence of Britain as a dominant colonial power.

3. The Seven Years’ War in North America

Initial French Successes

In the early stages of the Seven Years’ War, France enjoyed a string of victories in North America.

Leveraging strong alliances with Indigenous groups such as the Huron and the Algonquin, French forces gained the upper hand over the British.

In 1756, they captured Fort Oswego, a strategic position on Lake Ontario, significantly disrupting British supply lines and bolstering French control in the region.

The following year, French forces led by General Montcalm seized Fort William Henry, a major British stronghold near Lake George. The victory, however, was marred by the subsequent massacre of British prisoners by France’s Indigenous allies, an event that intensified animosity and spurred British determination to retaliate.

France’s initial dominance was rooted in their ability to navigate North America’s rugged terrain and cultivate local alliances. They established a robust network of forts and outposts that allowed them to control vast territories, stretching from Canada down the Mississippi River to Louisiana.

These early successes positioned France as the dominant power in the region, but their inability to sustain these gains would soon shift the balance in Britain’s favor.

Turning Points in 1758 and 1759

By 1758, the tide began to turn in favor of the British.

Under the leadership of Prime Minister William Pitt, Britain prioritized the North American theater, allocating significant resources and appointing capable military leaders.

British forces, supported by colonial militias, launched coordinated campaigns to dislodge the French from key positions.

In the summer of 1758, they captured Fort Duquesne, which was subsequently renamed Fort Pitt (modern-day Pittsburgh), securing the Ohio Valley for Britain.

That same year, they took Fort Frontenac, severing French supply lines and weakening their hold on the region.

The year 1759 proved to be a decisive turning point.

British forces achieved a landmark victory at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, just outside Quebec City.

General James Wolfe led the British troops in a daring assault that resulted in the death of both Wolfe and the French commander, General Montcalm.

Despite the heavy losses, the British emerged victorious, leading to the fall of Quebec. This victory marked the beginning of the end for French control in Canada. By 1760, British forces captured Montreal, effectively ending French resistance in North America and securing the continent for Britain.

Naval and Caribbean Campaigns

Britain’s Naval Supremacy

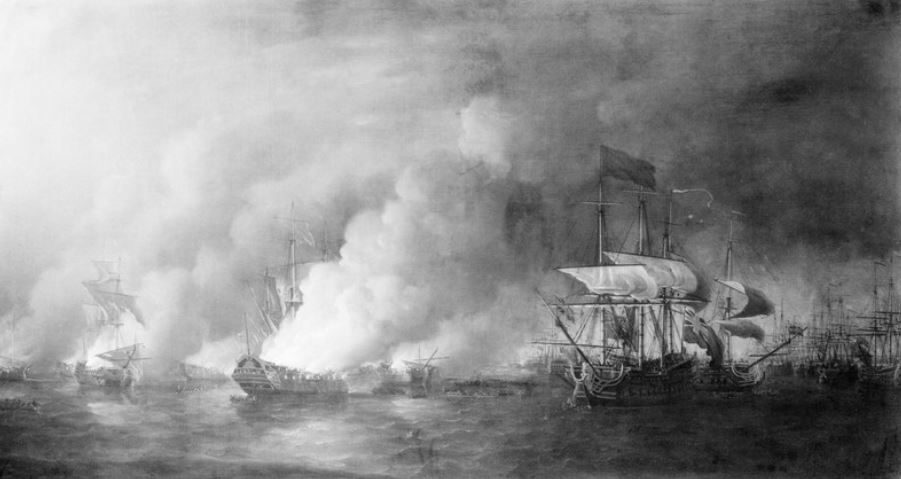

The Royal Navy was instrumental in Britain’s success during the war, ensuring dominance over the seas. Superior shipbuilding, experienced sailors, and effective strategies allowed Britain to outmaneuver the French navy.

In 1759, known as the “Annus Mirabilis” or “Year of Miracles,” the Royal Navy secured critical victories at the Battle of Lagos and the Battle of Quiberon Bay. These battles not only thwarted French plans to invade Britain but also crippled their ability to reinforce overseas territories.

Naval supremacy allowed Britain to enforce blockades that disrupted French trade and supply lines. This maritime dominance ensured that British forces in North America and the Caribbean received consistent reinforcements and supplies, giving them a significant edge over their French counterparts. It also enabled Britain to project power across the globe, turning the war into a truly global conflict.

4. The Caribbean Theater

While the struggle for North America drew significant attention, the Caribbean became a critical theater of war due to its lucrative sugar colonies.

The Role of Spain in The Seven Years’ War

While the situation in Central Europe had begun to stabilize, the conflict had taken on a truly global nature.

Spain, although a traditional ally of France, had remained neutral for much of the war. However, in 1759, the ascension of King Charles III to the Spanish throne shifted Spain’s stance.

Charles was concerned about the growing power of Britain, particularly its successes in North America and the Caribbean, and feared that British dominance in these regions might eventually encroach upon Spain’s own colonial holdings. As a result, Spain entered the war in 1762, siding with France in an effort to curb Britain’s rising influence.

The Spanish entry into the war, however, would have little success.

Operations in the Caribbean

British forces, led by naval commanders such as Admiral George Pocock, swiftly took the fight to Spain’s overseas possessions.

The islands’ sugar production was a cornerstone of European economies, making them highly contested territories. Britain targeted France’s Caribbean possessions to undermine their economic base and expand their own empire.

In 1759, British forces captured Guadeloupe, dealing a significant blow to French economic interests. The operation demonstrated Britain’s ability to project power far beyond North America and Europe.

The Caribbean campaign intensified in 1762 when Britain turned its attention to Spanish holdings after Spain entered the war as an ally of France.

The loss of Havana was a crippling blow to Spain, as the city was not only a key military and strategic base but also an essential hub in Spain’s trade routes in the Americas.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, the British captured Manila in the Philippines in October 1762. The loss of these two critical territories, combined with a series of defeats on the Iberian Peninsula, left Spain reeling. The Spanish had hoped to secure an advantage by entering the war but instead found themselves weakened and forced to concede several significant losses.

These victories not only expanded British territorial holdings but also cemented their position as the dominant colonial power. The wealth generated from the Caribbean colonies fueled Britain’s economy and allowed them to sustain the war effort.

The Legacy of the North American Campaign

The war in North America and the Caribbean ended French ambitions on the continent, leaving Britain in control of vast territories stretching from Canada to the Mississippi River. The Royal Navy’s dominance ensured Britain’s ability to maintain and expand its empire, while the Caribbean conquests enriched the British economy.

However, the cost of the war would sow the seeds of future conflicts, particularly the American Revolution, as colonial resentment grew over British taxation and policies in the aftermath of the war.

5. The Seven Years’ War in Europe

The Seven Years’ War in Europe would seea series of bloody battles, where no side could secure a decisive victory for long.

At the heart of the European theater was Frederick the Great of Prussia, whose leadership and military prowess would go on to define the course of the war.

Prussia, despite its early successes, faced significant setbacks during the war. The initially promising campaigns were overshadowed by a series of crushing defeats.

The Prussian army was outnumbered, and the coordinated forces of Austria, Russia, and France created immense pressure on Frederick’s troops.

One of the most devastating losses came at the Battle of Kunersdorf in 1759, where Frederick’s forces suffered catastrophic casualties, nearly breaking the backbone of the Prussian army.

Additionally, Russian forces had seized control of East Prussia, threatening to push deeper into Prussia’s heartland. Frederick was on the verge of collapse as his empire seemed to be unraveling.

However, Frederick the Great’s resilience and military genius would ensure Prussia’s survival. He was able to rally his forces and outmaneuver his opponents, even after these heavy losses.

By the time Empress Elizabeth of Russia died in 1762, Frederick’s situation had improved.

The death of Elizabeth led to a dramatic shift in Russian foreign policy. Her successor, Peter III, had a personal admiration for Frederick and was sympathetic to Prussia’s cause. Under Peter’s leadership, Russia withdrew from the conflict, and the tides of war shifted in Prussia’s favor.

This unexpected turn of events, combined with Frederick’s ability to regroup his forces and secure key victories, prevented Prussia from being defeated outright. By 1762, the alliance between Austria and Russia, which had been so crucial to the pressure on Prussia, had collapsed, allowing Frederick to press for peace on his own terms.

6. The Treaties of Paris and Hubertusburg

As the war dragged on, all the powers involved in the conflict were stretched to their limits.

The prolonged fighting had drained the coffers of every nation, and by 1762, there was growing fatigue and a desire for peace.

The British, in particular, had borne the brunt of the war’s financial costs, and the strain on their resources had become unsustainable.

In Europe, Frederick the Great, after enduring a long period of hardship, was eager to secure peace that would allow Prussia to retain its status as a major power. The war in Europe finally came to an end with two significant treaties that would reshape the balance of power on the continent and around the globe.

The first of these, the Treaty of Hubertusburg, signed in February 1763, marked the conclusion of hostilities in Central Europe.

The treaty essentially restored the pre-war borders, ensuring that the territorial status quo was maintained. Prussia retained Silesia, which had been a critical point of contention during the war, securing Frederick’s position as the unquestioned ruler of the region.

Despite the heavy toll the war had taken on Prussia, the treaty solidified its status as a dominant European power. Austria, having failed to regain Silesia, was forced to accept the outcome of the war and adjust its territorial ambitions accordingly.

Meanwhile, the broader, global conflict had been settled with the Treaty of Paris, signed five days before Hubertusburg.

This treaty had profound consequences for the colonial powers of the world.

For Britain, the Treaty of Paris was a resounding victory. The British gained control of Canada and Florida, as well as all French territories east of the Mississippi River, which significantly expanded British holdings in North America.

This territorial acquisition not only increased Britain’s influence in the Americas but also greatly enhanced its economic and strategic position in the New World.

France, on the other hand, was forced to cede much of its colonial empire.

The loss of New France (Canada) was a catastrophic blow, ending France’s aspirations of colonial dominance in North America.

However, France did retain its sugar-producing colonies in the Caribbean, such as Martinique and Guadeloupe, which were of immense economic value. France’s retention of these islands underscored their strategic importance, particularly in terms of the revenue they generated through the production of sugar and other valuable commodities.

The Treaty of Paris also had implications for Spain, which gained Louisiana in the west, compensating for the loss of Florida to Britain.

Spain’s acquisition of Louisiana was a significant territorial gain, but it came at the cost of Florida, which Britain had taken after Spain’s defeat in the Caribbean. Despite its territorial changes, the Treaty of Paris cemented Britain’s dominance over its colonial rivals, leaving it as the preeminent imperial power.

7. Consequences of the Seven Years’ War

The Seven Years’ War, a global conflict that spanned multiple continents, left a profound economic and political impact on all the nations involved.

At the heart of these consequences was the staggering financial cost of the war. The war’s immense expenditure led to massive debts for the European powers, with Britain and France among the most heavily burdened.

The war’s financial toll was especially severe for Britain, which, despite its territorial gains, faced mounting debt from the conflict’s extensive military campaigns.

For Britain, the economic impact of the war was particularly felt in the form of increased taxation. In an effort to recover the enormous costs of the war, Britain sought new sources of revenue, leading to an increase in taxes, particularly on its American colonies.

This shift in fiscal policy led to growing resentment among the colonists, who had long been accustomed to a relatively lenient system of taxation and governance. The British government’s attempts to enforce new taxes, such as the Stamp Act and the Townshend Acts, sparked outrage across the colonies. Colonists argued that they should not be taxed without representation in the British Parliament, a principle that would become a cornerstone of American revolutionary sentiment.

The financial strain also prompted Britain to increase its military presence in North America, which further fueled tensions with the colonists. The imposition of taxes to cover the costs of defending the colonies created widespread dissatisfaction, contributing to the political instability that would ultimately lead to the American Revolution in 1775.

Thus, the Seven Years’ War, while securing British imperial dominance, also sowed the seeds of discontent in the American colonies, a factor that would reshape the future of the British Empire and the course of world history.

For France, the economic consequences were equally dire.

France, having suffered significant territorial losses in the Treaty of Paris, faced not only the financial burden of the war but also the loss of its colonial possessions. In particular, the cession of Canada and the vast territories east of the Mississippi River to Britain undermined France’s position as a major colonial power.

The financial strain on the French state contributed to the growing discontent that would eventually culminate in the French Revolution of 1789. The inability of the French monarchy to manage the financial crisis, coupled with widespread social inequality, set the stage for radical political change in France.

The Seven Years’ War thus became a precursor to the upheavals that would reshape Europe and the Americas in the coming decades.

Shifts in Global Power

One of the most important outcomes was the rise of Britain as the dominant global power, particularly in terms of its imperial influence. The Treaty of Paris, which concluded the war, solidified Britain’s control over vast swathes of territory in North America, the Caribbean, and India. By securing Canada, Florida, and the territories east of the Mississippi, Britain expanded its empire significantly, cementing its position as the foremost colonial power of the 18th century.

Britain’s victory also marked the beginning of its dominance in India, a region that had long been contested by European powers. The weakening of France in India, following its defeat in the war, allowed Britain to take control of key territories, including Bengal. This laid the groundwork for the British Raj, which would later see the full-scale colonization of India by Britain in the 19th century.

Furthermore, the Seven Years’ War had a profound impact on the social and political landscape of Europe and the Americas.

The Seven Years’ War left a lasting impact on Central Europe, particularly on Prussia and Austria.

Prussia emerged as a major power, with the Treaty of Hubertusburg solidifying its control over Silesia and elevating its status in European politics.

For Austria, the war underscored the need for reforms, leading to military and administrative modernization under Maria Theresa.

Smaller German states within the Holy Roman Empire experienced increased vulnerability, as the conflict exposed their fragmented nature. The war redefined borders, alliances, and power dynamics, setting the stage for future geopolitical rivalries and influencing the region’s political landscape well into the 19th century.

Further Reading

If you enjoyed this article, you may enjoy these: