From the Anglo-Saxon kings to the modern-day Windsor dynasty, the English monarchy has shaped the course of a nation for over a millennium. But who among these crowned heads truly left their mark on history?

In this comprehensive ranking, we’ll journey through time, evaluating every ruling King and Queen of England and Britain from worst to best.

Our criteria? We’re looking at their impact on the nation’s welfare, military successes (or failures), economic policies, and social reforms. We’ll consider how they navigated the challenges of their time and whether England was better off at the end of their reign than at the beginning.

Prepare for controversy – ranking monarchs is no easy task, and opinions will undoubtedly differ. Some revered names might fall short, while unlikely heroes could rise to the top. So, dust off your history books and join us as we crown the best and dethrone the worst of England’s long-reigning monarchs.

56. Lady Jane Grey (1553)

Lade Jane Grey, The “Nine Days’ Queen” was a pawn in political machinations. Her reign was short and tragic, leaving no lasting legacy due to her quick overthrow by Mary I.

55. Edward V (1483)

Edward V was uncrowned and quickly deposed by his uncle Richard III. Edward V was also considered illegitimate. Edward V’s brief life and reign left little historical impact, overshadowed by the mystery of his disappearance.

54. Edgar the Ætheling (1066)

Proclaimed but never crowned, Edgar the Ætheling was the last male member of the royal house of Wessex. His brief and symbolic claim to the throne was overshadowed by William the Conqueror. He did however, survive until around 1125.

53. Edward VIII (1936)

Edward VIII’s brief reign ended in 1936 with his abdication to marry Wallis Simpson, a twice-divorced American. His abdication crisis significantly impacted the British monarchy’s future.

52. John (1199–1216)

King John is remembered as one of England’s most controversial kings.

His early reign was plagued by difficulties, particularly with regard to his territories in France. John’s attempts to recover lands lost by his father and brother, including the important duchies of Normandy, Anjou, and Maine, were largely unsuccessful. His failures in these campaigns led to significant territorial losses.

John’s heavy-handed taxation and arbitrary enforcement of the law generated widespread discontent among the nobility.

One of the most pivotal events of John’s reign was the Magna Carta, a document forced upon him by a group of rebellious barons in 1215. The Magna Carta, or “Great Charter,” was a landmark in the history of constitutional governance. It established principles of due process and limited the powers of the king. His refusal to abide by the terms of the charter contributed to ongoing instability and civil war.

John’s reign also saw his excommunication by Pope Innocent III due to a dispute over the appointment of the Archbishop of Canterbury.

51. Richard II (1377–1399)

Richard II ascended to the throne in 1377 at the age of ten, following the death of his grandfather, Edward III. His early years as king were characterized by a regency under the guidance of his uncles. When he came of age, Richard attempted to assert his authority and centralize power, which led to growing tensions with the nobility and Parliament.

One of the most notable events of Richard’s reign was the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381. This uprising was driven by economic hardship, oppressive taxation, and social inequality.

Richard’s policies, including his attempts to control and reform the court and his favoritism towards certain advisors, further alienated many of the powerful nobles.

In 1399, Richard’s reign came to a dramatic end when his cousin, Henry Bolingbroke returned from exile and raised an army to challenge Richard’s rule. Bolingbroke, who had been banished by Richard, was initially seeking to reclaim his confiscated lands but soon garnered widespread support and seized the throne.

He is often remembered as a tragic and ineffectual ruler whose reign was characterized by internal conflict and personal misjudgment.

50. Charles I (1625–1649)

Charles I’s rule was defined by a series of political and religious disputes that led to the English Civil War and significant changes in the governance of England.

His reign was soon marked by tensions with Parliament, which were exacerbated by his belief in the divine right of kings and his desire for absolute monarchical power. Charles’s approach to governance, which included bypassing Parliament and imposing taxes without its consent, created significant friction with the legislative body and fueled widespread discontent.

The situation deteriorated as Charles’s relationship with Parliament continued to sour. In 1642, the conflict between the king and Parliament erupted into the English Civil War.

The war was fought between the Royalists, who supported Charles I, and the Parliamentarians, led by figures such as Oliver Cromwell.

Charles’s inability to effectively manage the war and his refusal to negotiate with Parliament contributed to his eventual defeat. In 1646, Charles was captured and imprisoned. In 1649, Charles I was put on trial, found guilty of high treason and executed in front of a large crowd in Whitehall.

His execution led to the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of the Commonwealth of England under Oliver Cromwell.

49. Henry VI (1422–1461 & 1470–1471)

Henry VI’s reign was defined by extreme instability and a protracted period of civil war known as the Wars of the Roses.

His two separate periods of rule and the dramatic events surrounding them contributed to his complex and troubled legacy.

Henry VI became king of England as an infant in 1422, following the death of his father, Henry V. His early reign was characterized by the continued struggles of the Hundred Years’ War with France. During his minority, the kingdom was governed by a regency, which struggled to maintain control over the French territories.

As Henry reached adulthood, his lack of effective leadership skills and his mental instability began to cause significant problems. His reign was marked by a series of crises, including intermittent bouts of mental illness.

The Wars of the Roses, a series of dynastic conflicts between the rival houses of Lancaster (to which Henry VI belonged) and York, were a major feature of Henry’s reign. This led to his deposition in 1461.

Edward IV of the House of York succeeded Henry VI, marking the beginning of the first Yorkist rule.

Henry VI’s deposition did not end his troubles, as he was briefly restored to the throne in 1470. This short-lived restoration, lasted until 1471. His reign was marked by continued conflict and instability, culminating in his defeat at the Battle of Tewkesbury in 1471. Following this defeat, Henry VI was imprisoned in the Tower of London, where he was murdered under suspicious circumstances.

48. Edward II (1307–1327)

Edward II’s early years as king were marred by his apparent lack of political acumen and his preference for surrounding himself with favorites, notably Piers Gaveston.

Gaveston’s influence and the extravagant lifestyle he and Edward led created significant resentment among the English nobility. This led to a series of conflicts with powerful barons, who sought to curb the influence of Gaveston and assert their own power.

Edward’s reign was further troubled by his inability to manage the ongoing conflicts with Scotland. The wars with Scotland were unsuccessful; his defeat at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314 was a particularly crushing blow.

The defeat, led by Robert the Bruce, not only weakened Edward’s position but also emboldened Scottish resistance. The loss of Scottish territories and Edward’s perceived failures in the campaign significantly undermined his credibility as a king.

The situation deteriorated further when Edward’s relationship with Isabella of France, his wife, became strained.

Isabella, who had initially been an ally, eventually aligned with opposition factions to challenge Edward’s rule.

In 1327, amidst mounting pressure and continued internal strife, Edward II was forced to abdicate the throne in favor of his son, Edward III. His abdication was largely the result of the efforts of a coalition led by his wife Isabella and her lover, Roger Mortimer.

Edward was imprisoned and later died under suspicious circumstances, with many historians believing he was murdered.

47. Æthelred II ‘The Unready’ (978–1013 & 1014–1016)

Æthelred II, commonly known as Æthelred the Unready (978–1016), is remembered as one of England’s more troubled and controversial kings.

Æthelred became king at a young age, following the death of his half-brother, Edward the Martyr, in 978.

His reign was characterized by a series of conflicts with the Viking invasions, which were particularly devastating during his time.

The term “Unready” is derived from the Old English word “unræd,” meaning “ill-advised” or “poorly counseled,” reflecting perceptions of his poor leadership and lack of effective governance.

One of Æthelred’s most notable actions was the ordering of the St. Brice’s Day massacre in 1002, during which many Danish settlers in England were killed.

This brutal act was intended to quell Viking raids by removing a significant portion of the Viking threat within England, but it backfired, leading to further Viking invasions and reprisals. The Danish leader Sweyn Forkbeard responded by launching a series of devastating campaigns against Æthelred’s kingdom.

In 1013, Sweyn Forkbeard conquered much of England and was declared king, leading to Æthelred’s temporary exile. Æthelred returned to the throne in 1014 after Sweyn’s death, but his attempts to restore stability and repel Viking attacks continued to falter.

The constant threat of Viking raids led to significant discontent among the English nobility, who grew frustrated with Æthelred’s inability to effectively deal with the invasions and maintain order. This discontent contributed to his struggles in maintaining control and effectively governing the kingdom.

After Æthelred’s death, the Danish king Cnut successfully conquered England, marking the beginning of a new phase in English history under Danish rule.

46. Richard I (1189–1199)

Richard I, commonly known as Richard the Lionheart, is remembered as one of England’s most legendary and romanticized kings, celebrated for his military prowess, particularly during the Third Crusade.

However he was an absent King, that spent little time in England.

His primary focus was the Third Crusade, a major military expedition aimed at recapturing the Holy Land from Saladin, the Sultan of Egypt and Syria, who had recaptured Jerusalem in 1187.

Despite his reputation as a skilled and courageous military leader, Richard’s reign was marked by significant challenges beyond the Crusade. His absence from England for most of his reign left the kingdom under the control of his regents.

This absence created administrative and financial difficulties, as well as political unrest.

Financially, Richard’s involvement in the Crusade placed a heavy burden on England. To fund his campaigns, he imposed heavy taxes and raised substantial sums through the sale of royal lands and offices. His imprisonment on his return to England and subsequent ransome, almost bankrupted England.

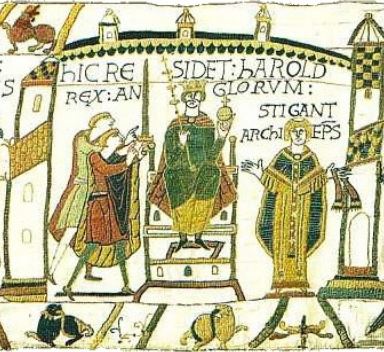

45. Harold II (1066)

Harold II, also known as Harold Godwinson, was an Anglo-Danish noble who took the throne upon Edward the Confessors death. Harold’s reign lasted less than a year, but it was pivotal in determining the future of England.

He was elected king by the Witenagemot (the council of nobles), a decision that was contested.

Harold’s reign was marked by immediate and intense challenges, with the invasion of of Harald Hardrada, the King of Norway, in northern England. Harold rapidly assembled his forces and defeated Hardrada at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in September 1066, a significant victory.

Just a few weeks later, William of Normandy launched his invasion of England. The Battle of Hastings, fought on October 14, 1066, became the defining moment of Harold II’s reign. Harold’s forces were eventually overwhelmed and he was killed in the battle.

The defeat at Hastings led to the rapid collapse of Anglo-Saxon resistance and paved the way for William the Conqueror’s successful claim to the English throne.

Harold II’s legacy is a poignant reminder of the transient nature of power and the dramatic impact of historical events.

44. Mary I ‘Bloody Mary’ (1553–1558)

Mary I is often referred to as “Bloody Mary,”. She is remembered for her attempts to restore Catholicism in England and for the persecution of Protestants during her short reign.

She was the daughter of Henry VIII and his first wife, Catherine of Aragon.

Mary ascended the throne after the death of her half-brother, Edward VI, who had tried to exclude her from the line of succession in favor of his Protestant cousin, Lady Jane Grey.

Mary overthrew Jane’s nine-day reign and was crowned queen. As a devout Catholic, Mary’s primary aim was to reverse the Protestant reforms initiated by her father and furthered by Edward. She sought to bring England back under the authority of the Pope and restore Catholicism as the state religion.

Her religious policies, however, are the most notorious aspect of her reign. Determined to stamp out Protestantism, Mary launched a brutal campaign of persecution against Protestants, which led to the execution of nearly 300 people, many of whom were burned at the stake. This persecution earned her the nickname “Bloody Mary,”

Mary’s marriage to Philip II of Spain, a staunch Catholic, fueled fears of foreign influence and intensified religious divides in England. Her marriage to Philip II of Spain was highly unpopular with the English people and Parliament, as it raised fears that England would become a satellite of the powerful Habsburg empire.

Mary’s foreign policy was another source of trouble. Her decision to support Spain in its war against France led to England’s humiliating loss of Calais in 1558, the last English possession on the European mainland.

The loss of Calais, coupled with her failure to produce an heir, further undermined her popularity and prestige.

She is often remembered as a tragic and unpopular monarch who ruled through fear and repression.

43. Stephen (1135–1154)

Stephen of Blois’s reign was marked by chaos, civil war, and instability, often referred to as “The Anarchy.”

His accession to the throne was highly contested and resulted in nearly two decades of conflict and disorder in England.

Stephen’s claim to the throne came after the death of his uncle, Henry I, who had no surviving legitimate male heirs.

Although Henry I had designated his daughter, Empress Matilda, as his successor, Stephen, a popular noble and grandson of William the Conqueror, seized the throne quickly, with the support of many barons and the Church. His swift coronation was seen by many as a way to prevent a female ruler from ascending, as the idea of a woman reigning as queen was deeply unpopular at the time.

However, his claim was not universally accepted, and Matilda, supported by a faction of nobles, including her half-brother Robert of Gloucester, launched a campaign to reclaim the throne.

This sparked a long and brutal civil war, with neither side able to gain a decisive advantage.

Local lords took advantage of the chaos to consolidate their own power, often building unauthorized castles and defying royal authority. This breakdown of central control led to a significant decline in law and order across the country.

The conflict eventually settled into a stalemate, with neither side able to claim a complete victory. In 1153, after years of inconclusive fighting, a peace was negotiated between Stephen and Matilda’s son, Henry of Anjou (later Henry II). This agreement, known as the Treaty of Wallingford, allowed Stephen to remain king for the rest of his life, but recognized Henry as his heir.

42. Eadwig (955–959)

Eadwig ruled as King of England from 955 to 959 CE. Ascending to the throne at about 15 years old, his short reign was marked by controversy and political turmoil.

He clashed with powerful figures like Dunstan, whom he exiled, and was later accused of misrule and hostility towards monasteries.

In 957, the kingdom was divided, with Eadwig ruling south of the Thames and his brother Edgar controlling the north.

Eadwig’s marriage to Ælfgifu was annulled by Archbishop Oda on grounds of consanguinity, further complicating his rule.

Traditionally, Eadwig was viewed as an incompetent ruler who lost northern England due to his failings.

41. James II (1685–1688)

James II’s reign was a period of significant political and religious turmoil in England, Scotland, and Ireland, and severe missteps.

James initially enjoyed widespread support upon his accession. His advocacy for religious tolerance, particularly for Catholics and Protestant dissenters, was progressive for its time and aligned with emerging Enlightenment ideals.

James also attempted to modernize the military and showed some skill in financial management.

However, his attempts to increase royal power at the expense of Parliament created political tensions and fears of absolutism.

James’s Catholicism and his efforts to promote Catholics to positions of power alarmed the Protestant majority, leading to widespread distrust. The birth of his Catholic son, which threatened to establish a permanent Catholic dynasty, proved to be the tipping point for many of his subjects.

James’s inflexibility and misreading of the political climate led to his downfall.

His flight from the kingdom when faced with William of Orange’s invasion was seen as an abdication of duty. This action, combined with his subsequent failed attempt to regain the throne through Ireland, resulted in a permanent alteration of the British constitution, establishing the principle of parliamentary sovereignty.

The Glorious Revolution that deposed him led to the Bill of Rights, further limiting royal power and cementing Protestant succession.

40. Harthacnut (1040–1042)

Harthacnut, son of Cnut the Great and Emma of Normandy, became King of England in 1040 after the death of his half-brother Harold Harefoot. He was already King of Denmark and ruled both kingdoms until his death in 1042.

Harthacnut’s reign in England was brief and tumultuous. He immediately imposed a heavy tax to pay for his fleet, causing resentment among his subjects.

In a show of brutality, he had Harold Harefoot’s body exhumed, beheaded, and thrown into a fen. He also ordered the killing of several nobles who had opposed his succession, such as Earl Eadwulf and the the harrying of Worcester.

Despite his harsh actions, Harthacnut made some conciliatory moves. He invited his half-brother Edward (later known as Edward the Confessor) to return from exile in Normandy, possibly intending to make him his heir. Harthacnut’s rule ended abruptly when he died at a wedding feast in 1042, likely from a stroke, leaving no heirs.

39. Edmund II ‘Ironside’ (1016)

Edmund Ironside, son of Æthelred the Unready, reigned as King of England for just seven months in 1016. His short rule was marked by constant warfare against the invading Danish forces led by Cnut the Great.

After his father’s death, he was proclaimed king by the citizens of London, while the Witan (assembly of Anglo-Saxon nobles) chose Cnut as king.

Edmund Ironside achieved a series of notable military victories against the Danish invaders led by Cnut, including raising the siege of London and defeating the Danes at Otford, before ultimately negotiating a peace treaty that divided England between himself and Cnut.

Edmund’s reign ended abruptly when he died on November 30, 1016, just weeks after this agreement. The circumstances of his death remain mysterious, with some suggesting assassination. Upon his death, Cnut became king of all England, marking the beginning of Danish rule.

38. George IV (1820–1830)

George IV previously served as Prince Regent during his father’s mental illness. He was known for his extravagant lifestyle. George IV was often criticized for his self-indulgence and debts and was also regarded as a selfish and unreliable monarch whose habits and appearance made him a subject of public ridicule in his later years.

37. George I (1714–1727)

George I, born in Hanover, became King of Great Britain and Ireland in 1714 following the death of Queen Anne. His accession, based on the 1701 Act of Settlement, marked the beginning of the Hanoverian dynasty.

George’s reign was characterized by a shift towards parliamentary governance. Unable to speak fluent English, and spending significant time of of the country, he relied heavily on his ministers, particularly Sir Robert Walpole, who became Britain’s first de facto Prime Minister. This period also saw the development of the cabinet system of government.

George faced challenges from Jacobite supporters of James Stuart, culminating in the unsuccessful 1715 rebellion.

His reign also witnessed the South Sea Bubble financial crisis in 1720.

36. Edward the Martyr (975–978)

Edward’s reign was plagued by numerous difficulties. The dispute over succession between Edward and his half-brother Æthelred created political tensions that would persist throughout his short time as king.

The “anti-monastic reaction” during his reign led to conflicts between nobles and religious institutions, potentially undermining the reforms and stability established by his father. Edward’s reportedly violent personality may have exacerbated these tensions and made effective governance challenging.

The most significant negative aspect of Edward’s reign was its abrupt and violent end. His murder at a young age, possibly orchestrated by those close to the throne, highlighted the instability of the period and the dangerous power struggles within the royal court. While his subsequent veneration as a saint provided some positive legacy, modern historians question whether this was truly merited given his character and the brevity of his rule.

35. Harold I ‘Harefoot’ (1035–1040)

Harold Harefoot ruled England from 1035 to 1040, succeeding his father Cnut the Great. His reign was contentious from the start, as he seized the throne despite his half-brother Harthacnut’s stronger claim. Harold’s rule was marked by political instability and conflict with his stepmother Emma of Normandy, whom he exiled.

Harold’s effectiveness as a ruler is debated. He maintained relative peace but faced challenges to his legitimacy. His most significant act was probably his role in the murder of Alfred Ætheling, which tarnished his reputation.

Harold’s legacy is limited due to his short reign. He died childless in 1040, leading to Harthacnut’s succession.

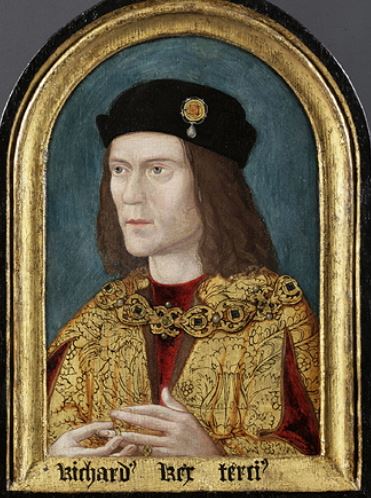

34. Richard III (1483–1485)

Richard III ruled England from 1483 to 1485, seizing the throne from his nephew Edward V. His brief reign was controversial from the start, marred by the disappearance of the “Princes in the Tower” – Edward V and his younger brother.

Despite his short rule, Richard implemented several notable reforms.

He introduced bail and the concept of blind justice into English law, established the Court of Requests for poor people’s petitions, and banned restrictions on the printing and sale of books. He also founded the College of Arms, which still operates today.

However, Richard faced significant opposition, culminating in Henry Tudor’s invasion in 1485. Richard was killed at the Battle of Bosworth Field, becoming the last English king to die in battle.

Richard III’s legacy is complex. For centuries, he was vilified as a murderous usurper, largely due to Shakespeare’s play. However, modern historians have reassessed his reign, highlighting his administrative skills and legal reforms.

33. Sweyn Forkbeard (1013–1014)

Sweyn Forkbeard’s reign, though brief, had a profound impact on England.

His series of invasions and raids from 1002 to 1013 destabilized the country, exploiting the weaknesses in Æthelred the Unready’s rule. Sweyn’s campaigns resulted in significant economic drain through the extraction of Danegeld, weakening England’s resources.

Although Sweyn’s direct rule lasted only five weeks, his invasion paved the way for his son Cnut’s eventual reign and the period of Danish rule in England. The swift submission of many English regions to Sweyn highlighted the fragility of Anglo-Saxon political unity.

32. William II ‘Rufus’ (1087–1100)

William II, known as ‘Rufus’ for his red hair, ruled England from 1087 to 1100. He succeeded his father, William the Conqueror, inheriting a kingdom still grappling with Norman rule.

Rufus’s reign was marked by conflict. He faced rebellions from Norman barons supporting his elder brother Robert’s claim to the throne. Despite this, he successfully defended his crown and even expanded his power, invading Scotland and Wales.

William was a controversial figure. He was criticized for his irreligious behavior and for keeping church positions vacant to appropriate their revenues.

Rufus’s reign saw the construction of several significant buildings, including Westminster Hall and the Tower of London’s White Tower. He also implemented some financial reforms, including the introduction of a new type of silver penny.

William II’s reign ended abruptly when he was killed by an arrow while hunting in the New Forest in 1100. The circumstances of his death remain mysterious, with some suggesting assassination. His death without an heir led to his younger brother Henry I seizing the throne, marking a new chapter in England’s Norman period.

31. Henry III (1216–1272)

Henry III became King of England in 1216 at the age of nine, inheriting a kingdom in turmoil due to the First Barons’ War. His long reign, lasting 56 years until 1272, was one of the longest in English history.

Henry’s early reign was dominated by regents, particularly William Marshal. Once he assumed personal rule, Henry faced challenges from powerful barons, culminating in the Second Barons’ War led by Simon de Montfort. This conflict resulted in the Provisions of Oxford, which attempted to limit royal power.

Despite political turmoil, Henry’s reign saw significant cultural and architectural achievements. He rebuilt Westminster Abbey in the Gothic style and was a patron of the arts. His reign also witnessed the emergence of Parliament as a political institution.

Henry was known for his piety and for his close ties to continental Europe, particularly France. However, his foreign policies, including failed attempts to regain lost territories in France, were often unpopular and costly.

Henry III’s legacy is mixed. While his reign saw important developments in law and government, including the reissue of Magna Carta, he was often criticized for financial mismanagement and favoritism towards foreign courtiers. Nevertheless, his long reign provided a period of relative stability that allowed for significant social and political evolution in medieval England.

30. William IV (1830–1837)

William IV’s reign, though relatively brief, was marked by significant successes and challenges.

On the positive side, his reign oversaw crucial reforms, most notably the Reform Act of 1832, which modernized the British electoral system and expanded suffrage. William also presided over the abolition of slavery in the British Empire, a landmark humanitarian achievement.

His background as a naval officer (the “Sailor King”) brought a pragmatic approach to governance, and he generally maintained good relations with Parliament. However, William’s reign also faced difficulties. The Reform Crisis initially strained his relationship with the Whig government, and his reluctance to engage in foreign affairs led to tensions with his Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston.

Personally, his earlier relationship with actress Dorothea Jordan and their ten illegitimate children caused some controversy. Despite these challenges, William’s reign marked an important transition period in British history, effectively bridging the gap between the excesses of his brother George IV and the long, stable reign of his niece Victoria, while overseeing significant social and political reforms.

29. Edward VI (1547–1553)

Edward VI’s brief reign saw the rapid advancement of Protestant reforms, transforming the Church of England and establishing many of the foundations for English Protestantism that would endure.

The young king showed intellectual curiosity and religious zeal, actively participating in theological discussions despite his age. The introduction of the Book of Common Prayer and the Forty-two Articles were major achievements that would shape English religious life for centuries.

However, the costly wars with Scotland and France drained the treasury and brought little tangible benefit. Additionally, the rapid pace of religious change caused social unrest in some areas, particularly among those who remained loyal to Catholicism.

Edward’s early death at 15 also left the succession in crisis.

28. George II (1727-1760)

George II was the last British monarch born outside Great Britain.

Continuing on from George I’s reign, his reign saw the continued rise of the position of Prime Minister, with Sir Robert Walpole effectively running the government. This furthered the development of Britain’s constitutional monarchy.

Domestically, George II presided over a time of relative stability and economic growth, with advances in agriculture, industry, and commerce.

The Jacobite Rising of 1745 was successfully suppressed, consolidating Hanoverian rule.

Internationally, Britain became increasingly involved in European and colonial conflicts, including the War of the Austrian Succession and the Seven Years’ War. These conflicts, while costly, ultimately expanded British influence globally, particularly in North America and India, laying the groundwork for the British Empire.

George II was also a patron of the arts and sciences, supporting the establishment of the British Museum and fostering cultural development.

However, his reign was not without criticism; he was often absent in Hanover, and his political interventions were sometimes seen as heavy-handed. Despite these shortcomings, George II’s reign is generally viewed as a period of growing prosperity and global influence for Britain, setting the stage for the country’s emergence as a world power in the following decades.

27. James I (1603–1625)

James I, and also King of Scotland as James VI, ascended to the English throne in 1603, uniting the crowns of England and Scotland. His reign, lasting until 1625, marked the beginning of the Stuart dynasty in England.

James’s rule was characterized by relative peace and prosperity. But he faced challenges including the Gunpowder Plot in 1605.

He was known as the “wisest fool in Christendom” for his scholarly nature but sometimes poor judgment in politics.

A significant achievement was the sponsorship of the King James Bible, which had a lasting impact on English language and culture. James also promoted colonization in North America, leading to the establishment of Jamestown.

However, James’s belief in the divine right of kings and his lavish spending led to conflicts with Parliament. His foreign policy, particularly his pursuit of peace with Spain, was also unpopular.

His reign set the stage for future conflicts between crown and Parliament. His approach to monarchy significantly influenced his son, Charles I, whose reign would culminate in the English Civil War.

26. Anne (1702–1714)

Queen Anne’s reign (1702–1714) marked the end of the Stuart dynasty and saw significant developments in British politics and society.

Her reign is often associated with the successful conclusion of the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714), leading to the Treaty of Utrecht, which expanded British influence abroad.

At home, she oversaw the Acts of Union in 1707, uniting England and Scotland into Great Britain.

However, Anne’s reign was also marked by political instability, particularly the rivalry between the Whigs and Tories, which hampered her leadership.

Anne struggled with health problems throughout her life and had no surviving children, leading to the Hanoverian succession after her death.

While some admire her for her efforts in securing peace and unity, others criticize her for indecisiveness and reliance on her ministers.

25. Eadred (946–955)

Eadred ultimately succeeded in consolidating control over Northumbria, a crucial achievement in maintaining the unity of the English realm.

His appointment of Osulf as ealdorman of Northumbria was a strategic move that helped stabilize the region under Anglo-Saxon rule. Eadred’s strong support for the Benedictine Reform movement also had lasting impacts on English religious life and monastic culture.

However, Eadred’s reign was not without its struggles. The initial loss of control over Northumbria to Viking kings and local magnates required significant military effort to reverse, likely straining resources and causing instability in the northern part of the kingdom.

His ill health in later years may have affected his ability to govern effectively. The fact that Eadred never married and left no direct heirs also created a potential succession issue.

24. Edward VII (1901-1910)

Edward VII’s reign was relatively brief, but marked a significant transition in British history and had a lasting impact on the monarchy and society.

As the eldest son of Queen Victoria, Edward brought a new style to the throne after his mother’s long period of mourning and seclusion. His reign, known as the Edwardian era, was characterized by luxury and opulence among the upper classes, but also by significant social reforms and technological advancements.

Edward played a crucial diplomatic role, using his personal charm and family connections to improve Britain’s international relations, particularly with France, which led to the Entente Cordiale in 1904. This diplomatic success earned him the nickname “Peacemaker.”

He modernized many royal traditions and ceremonies, making the monarchy more visible and accessible to the public.

Edward’s personal life, marked by a love of socializing, gambling, and extramarital affairs, sometimes drew criticism, but also contributed to his image as the “Uncle of Europe.”

Edward VII’s reign is generally remembered as a time of relative peace and prosperity, bridging the Victorian age with the modern era and setting the stage for the monarchy’s role in the 20th century.

23. Charles II (1660–1685)

Charles II (1660–1685), known as the “Merry Monarch,” restored the monarchy after the turbulent period of the English Civil War and the Interregnum, bringing stability and a sense of normalcy back to England.

His reign, known as the Restoration, was marked by a revival of culture, arts, and entertainment, as well as relative peace.

Charles was pragmatic and often sought to maintain a balance between conflicting political factions, particularly the royalists and parliamentarians, and between religious groups, as tensions between Protestants and Catholics persisted.

However, Charles struggled with financial dependency on Parliament, which limited his authority.

His secret deals with Catholic France (e.g., the Treaty of Dover) sparked controversy.

The religious tensions that plagued his reign, including the Popish Plot and the Exclusion Crisis, highlighted the fears of a Catholic succession, as Charles had no legitimate heirs and his brother, James, was Catholic.

The Great Plague of 1665 and the Great Fire of London in 1666 were major disasters that tested his leadership.

His reign is remembered for its efforts to heal a divided nation, though his failure to resolve the issue of succession set the stage for future conflicts in the Glorious Revolution of 1688.

22. Edmund I (939 – 946)

King Edmund I’s major success was the reconquest of the Five Boroughs (Lincoln, Leicester, Nottingham, Stamford, and Derby) from Viking control in 942. This victory demonstrated Edmund’s military prowess and his ability to push back against Viking incursions, continuing the work of his predecessors in consolidating English control.

Edmund also showed skill in diplomacy, maintaining strong alliances with continental rulers like Otto I of East Francia and Louis IV of West Francia.

He was an active legislator, issuing three law codes that addressed ecclesiastical matters and public order, particularly focusing on regulating blood feuds and promoting peace.

His reign, did however, see periods where Viking leaders ruled in York, indicating the ongoing struggle for control in northern England.

Edmund’s reign was cut short by his assassination in 946.

21. George V (1910–1936)

George V (1910–1936) reigned during one of the most transformative periods in British history, overseeing the nation through World War I (1914–1918) and the subsequent social, political, and economic upheavals.

His leadership during the war was steady, and he became a symbol of national unity and resilience.

George V’s decision to change the royal family’s name from the German-sounding House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha to the House of Windsor in 1917 was a shrewd political move. It aligned the monarchy with British patriotism and distancing it from anti-German sentiment.

But, his reign also saw the dissolution of much of the British Empire, with Ireland gaining independence and growing unrest in other colonies, marking the beginning of the Empire’s decline.

Domestically, George V had to navigate post-war economic hardships, including labor strikes and the General Strike of 1926. His reign saw the first Labour government come to power. It also also witnessed the extension of voting rights, which contributed to the modernization of British democracy.

Despite these challenges, George V was seen as a stabilizing figure, playing a key role in maintaining the monarchy’s relevance in a rapidly changing world. He was respected for his sense of duty, modesty, and ability to adapt to the dramatic shifts of the early 20th century.

20. Henry VIII (1509-1547)

Henry VIII’s reign was a transformative period in English history, characterized by both remarkable achievements and controversial decisions.

He will always be infamously known for his six wives, but his most significant accomplishment was the establishment of the Church of England. This increased royal power and reshaped the country’s religious landscape, though it also led to social upheaval and persecution.

Henry greatly expanded the Royal Navy, setting the foundation for England’s future maritime dominance, and fostered a cultural renaissance at his court.

He centralized power, reducing the nobility’s influence, but his later years were marked by tyrannical governance.

Financially, expensive wars and an extravagant lifestyle strained the treasury, leading to currency debasement.

His foreign policy, particularly costly wars with France, yielded few lasting gains.

Henry VIII’s legacy remains complex and often contradictory; while he’s remembered as a larger-than-life figure who fundamentally altered England’s trajectory, his reign was also characterized by violence, instability, and personal excesses.

19. William III and Mary II (1689–1702)

William III and Mary II ruled England, Scotland, and Ireland jointly from 1689 to 1694, and William continued as sole monarch until 1702.

Their accession, known as the Glorious Revolution, marked a significant shift in English governance.

Their reign saw the establishment of the Bill of Rights in 1689, limiting royal power and strengthening Parliament’s role. This period also witnessed the formation of the Bank of England and the beginnings of a two-party political system.

William, often absent fighting in Ireland and continental Europe, left much domestic governance to Mary.

His victories, particularly at the Battle of the Boyne, secured Protestant succession but led to lasting tensions in Ireland.

The reign was marked by warfare, including the Nine Years’ War against France, which strained national finances but established England as a major European power.

After Mary’s death in 1694, William ruled alone. His reign saw further constitutional developments and the Act of Settlement 1701, which established the Protestant succession.

William and Mary’s rule solidified constitutional monarchy in Britain, promoted religious toleration (though limited), and set the stage for Britain’s emergence as a global power in the 18th century. The changes during their reign significantly shaped modern British governance.

18. Edward IV (1461–1470 & 1471–1483)

Edward IV was a central figure in the Wars of the Roses, between the houses of York and Lancaster.

His reign is noted for bringing a degree of stability to England after years of civil war, largely due to his military prowess and decisive victories over his rivals, particularly his triumph at the Battle of Towton in 1461.

Edward restored the power of the Yorkist faction and was known for his strong leadership, administrative reforms, and efforts to restore royal finances.

He also fostered economic growth by promoting trade and re-establishing law and order in a kingdom weary of conflict.

Edward’s personal choices, including his secret marriage to Elizabeth Woodville, alienated key nobles. This led to internal divisions and the brief overthrow of his rule by the Earl of Warwick in 1470.

He regained the throne in 1471 but continued to face opposition from disaffected nobles.

Edward’s sudden death in 1483 at a relatively young age left his young son, Edward V, vulnerable to usurpation, which ultimately led to the rise of Richard III.

His reputation is that of a capable and charismatic ruler who could not fully protect his dynasty from the internal conflicts that defined the late 15th century.

17. Henry IV (1399–1413)

Henry IV became the first king of England from the House of Lancaster after usurping the throne from Richard II, marking the start of the Lancastrian dynasty.

His reign was marked by challenges to his legitimacy, as his claim to the throne was not universally accepted, leading to multiple rebellions, including the Percy Rebellion (1403) and Owen Glendower’s Welsh uprising (1400–1415).

Henry spent much of his reign defending his crown from internal unrest, and his rule was defined by the ongoing struggle to maintain authority and stability in the face of opposition from both nobles and external threats.

Despite these challenges, Henry IV managed to consolidate power and lay the foundation for his dynasty’s continued rule. He showed military skill in quelling rebellions, particularly his victory at the Battle of Shrewsbury in 1403, which crushed the Percy rebellion.

His reign also saw the strengthening of parliamentary authority, as Henry frequently relied on Parliament for financial support in his military campaigns, giving it a more significant role in governance.

Henry IV’s health deteriorated during the later years of his reign, and his rule was increasingly troubled by personal illness, limiting his ability to govern. After his death in 1413, his son, Henry V, inherited a more stable kingdom that set the stage for the future successes of his son, Henry V.

16. George III (1760–1820)

George III is one of the most well-known monarchs in British history, with a reign that spanned six decades During this time Britain underwent significant social, political, and economic changes.

His rule saw the loss of the American colonies following the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783) – a defeat that dealt a blow to Britain’s global standing and severely impacted his reputation.

Despite this, George III’s reign is also associated with Britain’s victories in the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815), which solidified its position as a leading world power. He supported efforts to defeat Napoleon, and the victory at Waterloo in 1815 marked the zenith of British military power.

Domestically, George III’s reign witnessed the early stages of the Industrial Revolution, which transformed the economy, society, and urban landscape of Britain.

His reign was also characterized by significant political developments, including the struggles between the monarchy and Parliament over power, as well as growing demands for political reform.

George’s opposition to Catholic Emancipation, along with his views on royal authority, often placed him at odds with political leaders.

In his later years, George III suffered from recurrent bouts of mental illness, most famously during the “Regency Crisis” of 1788–1789, which eventually led to his son, the future George IV, acting as Prince Regent from 1811 onwards. His mental health problems overshadowed the final years of his reign, contributing to a sense of national uncertainty.

George III had personal virtues, dedication to duty, and he showed leadership during the challenges he faced in navigating Britain through an era of immense change.

15. Edgar the Peaceful (959–975)

Edgar became king of all England on his brother’s death. Ascending to the throne after a period of unrest under his predecessors, Edgar’s reign was marked by relative internal peace, earning him the epithet “the Peaceful.”

Edgar mainly followed the political policies of his predecessors, but there were major changes in the religious sphere. One of Edgar’s most significant achievements was his support for the monastic reform movement, working closely with figures such as Dunstan, the Archbishop of Canterbury, to restore and expand monastic institutions throughout the kingdom.

Edgar’s major administrative reform was the introduction of a standardised coinage in the early 970s to replace the previous decentralized system.

He also issued legislative codes which mainly concentrated on improving procedures for enforcement of the law.

Edgar’s reign is often considered a golden age when England was free from external attacks and internal disorder and the pinnacle of Anglo-Saxon culture.

Edgar the Peaceful is remembered as a strong and effective ruler who brought a period of stability and consolidation to the Anglo-Saxon kingdom. This was particularly impressive given the various factions of the kingdom. Edgar is also credited with strengthening the monarchy’s authority, building upon the centralized power established by earlier kings like Alfred the Great and Athelstan.

Edgar also maintained a powerful navy and conducted a symbolic naval ceremony in Chester, where several regional kings pledged their allegiance to him, showcasing his influence over Britain’s other rulers.

14. Elizabeth II (1952–2022)

Elizabeth II was the longest-reigning monarch in British history. Her reign spanning 70 years and witnessing profound global and national changes.

Ascending the throne in 1952, she guided the monarchy through the transformation of Britain from an imperial power to a modern, multicultural nation.

Elizabeth oversaw the dissolution of the British Empire and the establishment of the Commonwealth, an organization of former colonies united in partnership.

Her reign was marked by significant political and social shifts, from the post-war recovery and the Swinging Sixties to the challenges of economic austerity in the 1970s and 1980s, as well as evolving public attitudes toward the monarchy.

Elizabeth II’s steadfast dedication to public service and duty earned her widespread respect. Her ability to remain a figure of continuity amidst rapid societal change contributed to the monarchy’s stability.

She carried out her ceremonial and constitutional roles with diligence, representing Britain on the global stage and fostering diplomatic relationships with world leaders.

However, Elizabeth II’s reign was not without difficulties. The monarchy faced several crises, including the public’s response to the royal family’s handling of Princess Diana’s death in 1997, strained relations and scandals within the royal family, and growing questions about the monarchy’s relevance in modern society.

13. Edward the Confessor (1042–1066)

Edward the Confessor (1042–1066) was one of the last Anglo-Saxon kings of England. He was known for his pious nature and efforts to maintain peace during a time of political instability.

His reign followed a period of Danish rule, and his ascension helped restore the Anglo-Saxon monarchy.

Edward demonstrated considerable diplomatic skill. He successfully preserved English independence from continental influences, particularly the ambitions of Norway and Denmark. This was crucial in an era when Scandinavian rulers still had designs on the English throne. Edward’s ability to maintain England’s autonomy without resorting to costly wars showcased his subtle yet effective approach to international relations.

Perhaps Edward’s most visible and lasting legacy is Westminster Abbey. This magnificent church, which he commissioned and saw largely completed in his lifetime, represented a leap forward in English architecture. The Abbey introduced Romanesque style to England on a grand scale, inspiring a wave of church building and renovation across the country. Beyond its architectural significance, Westminster Abbey became a potent symbol of the English monarchy’s power and prestige, a role it continues to play to this day.

On the domestic front, Edward implemented several important reforms. He overhauled the English monetary system, improving the quality and consistency of coinage. This helped facilitate trade and strengthen the economy. Edward also worked to enhance local government structures, laying the groundwork for administrative developments that would be built upon by future monarchs.

Edward will be remembered for his failure to produce an heir, which led to uncertainty over the succession. His death in 1066 set the stage for a power struggle that culminated in the Norman Conquest.

Edward is often regarded as a model of Christian kingship and remembered for his role in the legal, economic, cultural and religious life of England.

12. Victoria (1837–1901)

Queen Victoria’s reign was the longest in British history at the time. Her 63-year rule saw Britain’s evolution into a constitutional monarchy, with the Queen’s role becoming more symbolic as Prime Ministers gained greater political influence.

The Victorian era was marked by Britain’s industrial and economic dominance, expansive colonial growth, and significant social reforms.

Under Victoria, the British Empire reached its zenith, covering nearly a quarter of the Earth’s surface.

This period saw remarkable technological advancements, including the expansion of railways, the telegraph, and later the telephone.

Victoria’s personal life, particularly her deep mourning following Prince Albert’s death in 1861, had a profound impact on British society and the monarchy’s public image.

Despite periods of unpopularity, especially during her prolonged seclusion, Victoria ultimately became a revered symbol of British imperial power and moral propriety.

Her reign oversaw significant social changes, including reforms in education, labor laws, and voting rights, though Victoria herself often held conservative views.

The era also faced challenges, including the Irish Potato Famine, the Crimean War, and colonial conflicts like the Indian Rebellion of 1857. Nevertheless, Victoria’s reign is generally remembered as a time of peace, prosperity, and cultural flourishing, with advancements in literature, science, and the arts.

Her numerous descendants, married into royal families across Europe, earned her the nickname “Grandmother of Europe.”

11. Henry VII (1485–1509)

Henry VII’s reign ushered in the Tudor dynasty and the early modern period.

As the victor of the Wars of the Roses, Henry brought stability to a kingdom long plagued by civil strife.

His reign was characterized by consolidation of power and economic prudence, laying the foundation for England’s future prosperity and influence.

Henry’s primary achievement was establishing political stability through a combination of strategic marriages, diplomatic alliances, and astute management of the nobility.

He strengthened the monarchy’s position by limiting the power of the aristocracy and enhancing royal finances through efficient taxation and frugal spending.

His creation of the Court of Star Chamber improved law enforcement and reduced the threat of noble insurrections.

Economically, Henry VII promoted trade, particularly the wool trade, and encouraged exploration, laying the groundwork for future English naval power. However, His methods of raising revenue, particularly through bonds and recognizances, were often seen as oppressive and arbitrary.

His foreign policy was largely peaceful, preferring diplomacy and trade agreements to costly wars.

The most notable diplomatic success was the marriage of his son Arthur (and after Arthur’s death, his son Henry) to Catherine of Aragon, solidifying an alliance with Spain.

He faced several pretenders to the throne, most notably Lambert Simnel and Perkin Warbeck, though he successfully suppressed these threats.

He left a solvent government, a strengthened monarchy, and a more unified kingdom to his son, Henry VIII. His policies of peace and economic development set the stage for the English Renaissance and the country’s emergence as a major European power in the 16th century.

10. Edward I “Longshanks” (1272–1307)

Edward I’s reign was a period of significant expansion, legal reform, and architectural achievement that profoundly shaped England’s future.

Known was “Longshanks” for his height and “Hammer of the Scots” for his military campaigns.

His most notable accomplishments include the conquest of Wales, which he incorporated into England through military campaigns and a series of imposing castles. This expansion was accompanied by administrative reforms that brought Welsh law more in line with English practices.

Edward’s attempts to dominate Scotland, while initially successful, ultimately led to prolonged conflict and resistance, exemplified by figures like William Wallace and Robert the Bruce.

Edward I was a great reformer. He expanded and codified English common law, earning him the moniker “English Justinian.”

His legal reforms, including the Statute of Westminster and the Statute of Mortmain, strengthened royal authority and laid the groundwork for England’s future legal system.

He also reformed Parliament, establishing the Model Parliament of 1295, which included representatives from the commons as well as the nobility and clergy, setting a precedent for broader representation.

Edward I was also a prolific builder. Beyond his military castles in Wales, he initiated the construction of many English castles and fortified towns. His reign saw the rebuilding of Westminster Abbey in its current Gothic style and the creation of a series of Eleanor Crosses in memory of his first wife.

His wars and building projects were however, expensive, leading to heavy taxation and occasional conflicts with the barons and the Church.

His expulsion of the Jews from England in 1290 was a dark chapter, reflecting the anti-Semitism of the time.

Edward I is generally remembered as one of England’s most effective monarchs. His legal and administrative reforms, territorial expansions, and architectural legacy had lasting impacts.

9. George VI (1936–1952)

Thrust onto the throne following his brother Edward VIII’s abdication, George VI faced the daunting task of restoring public faith in the monarchy.

His reign was defined by his steadfast leadership during World War II, where he became a symbol of national resistance and resilience.

George VI’s most significant achievement was his role during the war. He and his family remained in London during the Blitz, visiting bomb sites and munitions factories, which greatly boosted public morale.

His radio broadcasts, delivered despite his speech impediment, became a source of inspiration for the nation.

The King’s close working relationship with Winston Churchill was also crucial in maintaining national unity during this critical period.

Post-war, George VI presided over the transition of the British Empire into the Commonwealth, showcasing diplomatic skill in maintaining ties with former colonies as they gained independence.

His also reign saw the implementation of major social reforms, including the establishment of the National Health Service, though these were primarily driven by the government rather than the monarch.

The stress of wartime leadership and heavy smoking took a toll on his health, leading to his premature death at 56.

George VI’s legacy is one of quiet heroism and dedication to duty. He restored dignity to the throne after the abdication crisis and provided crucial leadership during Britain’s “finest hour.” His reign also marked the transition from the old imperial order to the modern era, setting the stage for the long and successful reign of his daughter, Elizabeth II.

8. William I ‘The Conqueror’ (1066–1087)

William the Conqueror (1066–1087) is one of the most pivotal figures in English history, best known for leading the Norman Conquest of England.

William Duke of Normandy, claimed the English throne after the death of Edward the Confessor, asserting that Edward had promised him the crown. In 1066, he invaded England and defeated King Harold Godwinson at the Battle of Hastings, This marked the beginning of Norman rule in England and the transformation of the country’s culture, governance, and social structure.

William’s reign as king was marked by efforts to consolidate his power and establish Norman dominance over the Anglo-Saxon nobility.

He implemented widespread changes, including the construction of castles, such as the Tower of London, to secure his rule and control rebellious regions.

He also redistributed land to his Norman followers, replacing much of the Anglo-Saxon aristocracy with Norman nobles. This reshaped the English feudal system and strengthened the monarchy’s authority.

One of William’s most lasting achievements was the commissioning of the Domesday Book in 1086, a comprehensive survey of England’s landholdings and resources, which provided a foundation for efficient governance and taxation.

He did however face several revolts, which he dealt with. This included uprisings in the north of England, which he brutally suppressed in what became known as the “Harrying of the North,” a campaign that devastated the region for many years.

His rule also led to tensions between England and Normandy, as William had to balance his duties as both king of England and duke of Normandy, defending his holdings on both sides of the English Channel.

William’s legacy is far-reaching. He transformed England’s legal, social, and political systems. His introduction of Norman culture, language, and governance, influenced everything from architecture to the legal system.

While his methods were often harsh, William is remembered as a determined and effective ruler who forever changed the course of English history.

7. Elizabeth I (1558–1603)

Elizabeth I was the last monarch of the Tudor dynasty. Her reign, known as the Elizabethan Era, was a time of political stability, cultural flourishing, and the rise of England as a global power.

Ascending the throne during a period of religious and political turmoil following the reigns of her Catholic half-sister Mary I and her Protestant father Henry VIII, Elizabeth skillfully navigated these challenges by establishing the Elizabethan Religious Settlement, which aimed to create a middle ground between Catholicism and Protestantism. This policy helped ease tensions and secured her popularity among a divided populace.

Elizabeth’s reign saw significant achievements in foreign policy, most notably England’s defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, a victory that solidified England’s naval supremacy and marked a turning point in its rivalry with Catholic Spain.

Though often pressured to marry to secure an heir and form alliances, Elizabeth remained unmarried, earning her the title “The Virgin Queen” and allowing her to maintain control over her own political destiny.

Culturally, the Elizabethan Era is often regarded as a golden age. Elizabeth was a great patron of the arts, and her reign coincided with the works of literary giants like William Shakespeare and Christopher Marlowe.

England experienced a flourishing of drama, literature, music, and exploration, with figures such as Sir Francis Drake and Sir Walter Raleigh leading expeditions that expanded England’s influence abroad.

Her failure to secure a direct heir led to uncertainty over the succession, which would eventually pass to her cousin, James VI of Scotland, uniting the crowns of England and Scotland.

Elizabeth I’s legacy is one of strength, resilience, and brilliance. She is remembered as a monarch who presided over England’s transformation into a major European power, both militarily and culturally, and her careful management of religious, political, and foreign affairs ensured that her reign was one of relative peace and prosperity.

6. Henry II (1154–1189)

Henry II was the first Plantagenet king of England and is remembered for his significant legal, administrative, and territorial reforms.

Ascending the throne after years of civil war known as “The Anarchy,” Henry worked to restore order and strengthen royal authority.

He is most notable for his contributions to the development of English common law, establishing a more systematic and accessible legal framework that reduced the influence of feudal lords and centralized justice under the crown.

His reforms, including the introduction of trial by jury and the expansion of royal courts, had a lasting impact on the English legal system.

Henry II’s reign also saw the expansion of the Angevin Empire, which, at its height, spanned much of modern-day England, western France, and parts of Ireland.

His marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine brought significant territories in France under his control, making him one of the most powerful monarchs in Europe.

Managing such a vast empire was a constant challenge, and Henry faced rebellions and conflicts, both from within his own family and from rival powers. His sons—most famously Richard the Lionheart and John—rebelled against him at various points, often spurred by their mother, Eleanor, leading to familial strife throughout his reign.

One of the defining events of Henry’s rule was his conflict with Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury. Initially close allies, the two clashed over the rights of the Church versus the authority of the crown. This conflict culminated in Becket’s assassination in 1170 by knights who believed they were acting on Henry’s wishes. The murder shocked Christendom, and Henry had the humility to do public penance for his perceived role in the event.

Henry II is regarded as a transformative monarch who modernized the English state.

5. Henry V (1413–1422)

Henry V is one of England’s most celebrated warrior kings.

His victory at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415 remains one of the most famous in English history, showcasing his leadership, tactical genius, and ability to inspire his troops despite being heavily outnumbered. This victory helped solidify his reputation as a heroic and effective ruler and greatly strengthened English claims to the French throne.

After Agincourt, Henry V continued his military campaigns in France, culminating in the Treaty of Troyes in 1420, which recognized him as the heir to the French throne. This treaty effectively made him the ruler of both England and large parts of France.

His marriage to Catherine of Valois, daughter of the French king Charles VI, further cemented his position and was seen as a diplomatic triumph that brought temporary peace between the two nations.

This period marked the height of English power in France, and Henry seemed poised to unite the two kingdoms under his rule.

Domestically, Henry V was an effective ruler who maintained strong royal authority. He promoted law and order, dealt decisively with rebellion, and curbed the power of overmighty nobles.

His leadership was marked by a strong sense of duty and piety, and he was seen as a just and competent monarch. He also supported the church, using his reign to promote religious orthodoxy and suppress the Lollard movement, which sought religious reform.

Henry’s reign was cut short when he died unexpectedly in 1422 at the age of 35, likely from dysentery. His death left his infant son, Henry VI, as king of both England and France, but his gains in France soon began to unravel, leading to the eventual loss of English territories there and contributing to the instability of the Lancastrian dynasty.

He is often idealized as a model of medieval kingship—brave, determined, and successful in war. His victories in France, particularly Agincourt, and his ability to maintain order at home made him a national hero.

4. Henry I (1100–1135)

Henry I was the fourth son of William the Conqueror. He was a shrewd and capable ruler who strengthened royal authority, reformed governance, and consolidated power in both England and Normandy.

His reign began after the unexpected death of his older brother, King William II, in a hunting accident. Seizing the opportunity, Henry quickly moved to secure the throne, issuing the Charter of Liberties, a document that promised to limit royal abuses and respect the rights of barons and the church.

One of Henry’s key achievements was the reform of the legal and administrative systems.

He expanded the use of royal justice, improving governance and centralizing control over the kingdom.

His appointment of skilled administrators, such as Roger of Salisbury, helped streamline the collection of royal revenues and created a more efficient and organized government. Henry is often credited with laying the foundations for what would later become the English Exchequer, establishing stronger royal financial oversight.

Henry’s reign was also marked by his efforts to secure his control over Normandy, which had been contested by his older brother, Robert Curthose. In 1106, Henry defeated Robert at the Battle of Tinchebray, capturing him and reuniting England and Normandy under a single ruler. This victory allowed him to maintain the vast Anglo-Norman empire.

The death of his only legitimate son, William Adelin, in the White Ship disaster of 1120 created a succession crisis. With no surviving male heir, Henry named his daughter, Matilda, as his successor. However, his nephew, Stephen of Blois, seized the throne, leading to period known as The Anarchy.

Henry I’s legal and financial reforms had a lasting impact, and his reign is often seen as a period of consolidation and recovery after the tumultuous years following the Norman Conquest. Henry I is recognized as one of the more effective Norman kings, whose reign helped shape the future of English governance.

3. Cnut the Great (1016–1035)

Cnut the Great, also known as Canute, was a Viking king who ruled over a vast North Sea empire that included England, Denmark, Norway, and parts of Sweden.

His reign is remarkable for transforming the Viking ruler from a foreign conqueror into a competent and respected English king.

After defeating the English king Edmund Ironside at the Battle of Assandun in 1016, Cnut became the king of England, consolidating his rule through a mixture of force and diplomacy. His reign brought a period of stability to a country that had been ravaged by decades of Viking invasions and internal conflict.

Cnut’s ability to maintain control over England, was due in part to his pragmatic approach to governance. He retained many Anglo-Saxon nobles in positions of power, integrated his Scandinavian followers into the English nobility, and respected the existing laws and institutions. This helped him win the support of both the English aristocracy and the church.

He also proved to be a capable military leader and diplomat, maintaining peace in England while expanding his influence across Scandinavia, particularly in Denmark and Norway.

One of Cnut’s most lasting achievements was his ability to balance the interests of his vast empire.

His empire helped foster a period of prosperity through trade across the North Sea, linking the economies of England and Scandinavia. Cnut’s reign also marked a shift in Viking culture, as he embraced Christianity and worked to integrate his realm into the broader Christian world, further strengthening his rule.

Cnut’s reign is often seen as a high point of Viking rule in England, marked by relative peace, prosperity, and effective governance. His legacy includes his reputation as a strong, fair ruler and the story of his humility.

2. Æthelstan (924–939)

Æthelstan was the first King of a united England and one of the most accomplished Anglo-Saxon rulers.

The grandson of Alfred the Great, Æthelstan’s reign is notable for his military successes, consolidation of power, and diplomatic achievements.

One of Æthelstan’s greatest achievements was his decisive victory at the Battle of Brunanburh in 937.

This battle saw Æthelstan defeat a coalition of Scottish, Norse, and Strathclyde armies, solidifying his control over England and earning him the reputation as one of the most formidable military leaders of his time.

This victory marked a turning point in the unification of England, ensuring that the kingdom would not fragment again after his death.

His success in warfare extended beyond England, as he also maintained influence over Wales and secured alliances through diplomacy with rulers across Europe, including marriages and treaties that linked England with the royal houses of France, Germany, and Norway.

In addition to his military prowess, Æthelstan was known for his administrative reforms and promotion of justice.

He centralized the kingdom’s governance, introduced legal codes that promoted peace and order, and strengthened the church’s role in society. His legal reforms focused on issues like theft and corruption, helping to maintain stability in the kingdom.

Æthelstan was also a great patron of the church, fostering relationships with important ecclesiastical figures and promoting religious reforms that helped align England with the broader Christian world.

Æthelstan’s court became a center of learning and culture, attracting prominent scholars from across Europe. Æthelstan also amassed a significant collection of religious relics, which helped cement his status as a pious and devout ruler.

Æthelstan’s death led to brief instability, as Viking invasions resumed under the leadership of Olaf Guthfrithson of Dublin, and some of the northern territories fell out of English control. However, the foundations laid during his reign enabled future kings to maintain a unified England.

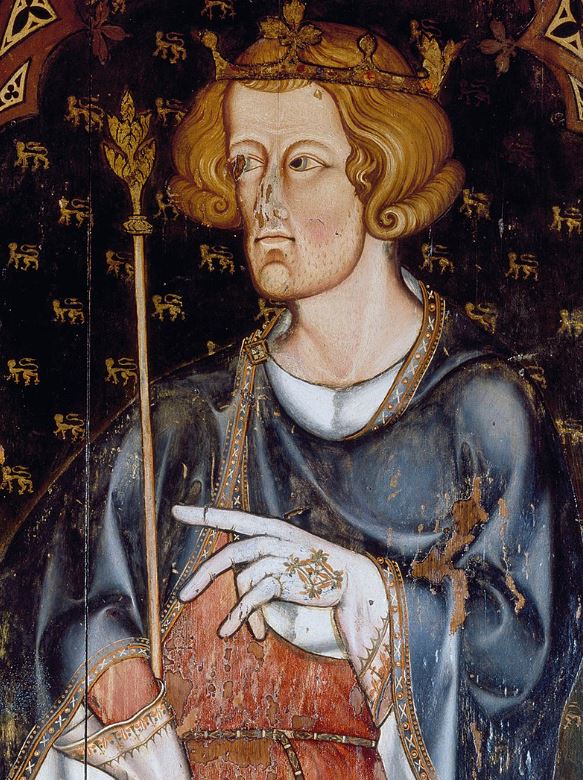

1. Edward III (1327–1377)

Edward III England’s most successful and influential medieval monarchs.

His reign saw the beginning of the Hundred Years’ War with France and the establishment of England as a formidable military power.

Known for his military leadership, administrative reforms, and efforts to strengthen the monarchy, Edward III’s legacy is shaped by both his martial achievements and the long-term consequences of his ambitious campaigns.

Edward III came to the throne after the deposition of his father, Edward II, in 1327. Early in his reign, his government was dominated by his mother, Isabella of France, and her lover, Roger Mortimer, but by 1330, Edward had asserted his authority by overthrowing and executing Mortimer. From this point on, Edward ruled in his own right, focusing on restoring the prestige of the English crown and expanding its power.

One of the defining aspects of Edward’s reign was his claim to the French throne, which initiated the Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453). Edward’s military campaigns in France were marked by a series of stunning victories, most notably at the Battle of Crécy in 1346 and the Battle of Poitiers in 1356.

These victories, achieved through superior tactics and the effective use of longbowmen, established England as a dominant force in European warfare and solidified Edward’s reputation as a brilliant military commander.

Edward also oversaw the successful siege of Calais, securing a vital foothold in France that would remain under English control for over two centuries.

Edward III’s reign also saw significant developments in the structure of English government and society.

He fostered the growth of parliamentary institutions, regularly summoning Parliament to approve taxes for his military campaigns, which helped establish the precedent for parliamentary consent in matters of taxation.

His creation of the Order of the Garter in 1348, an order of chivalry, reflected his promotion of knighthood and the ideals of medieval chivalry.

The outbreak of the Black Death in 1348–1350 devastated England during his reign. This event killed a significant portion of the population and causing widespread social and economic disruption. His government managed to maintain control and stability, the long-term effects of the plague changed the social fabric of the country.

Edward III is regarded as one of England’s greatest warrior kings. His military achievements, particularly in France, and his role in establishing England as a major European power earned him enduring fame. His reign also contributed to the development of English national identity.

Further Reading

If you enjoyed this article, you may enjoy these:

- What happened to Edgar the Aetheling?

- How did Charlemagne improve the lives of people in Europe?

- Why was the crowning of Charlemagne so important?

- How President Andrew Jackson Caused the Economic Crisis of 1837

- Why was Lady Jane Grey accused of treason?

- Why did General Robert E. Lee surrender at Appomattox?

You may also enjoy these articles about Medieval Europe: