We all know Alaska was once part of the Russian Empire, but what about before the fur traders arrived?

From the expert hunters and fishers of the Inuit and Yup’ik in the north and west to the complex societies of the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian in the southeast, Alaska’s indigenous populations thrived for millennia. Their legacy continues to shape the Alaskan identity, evident in everything from place names to cultural traditions.

Dive deeper and discover the fascinating story of the indigenous peoples who called Alaska home long before European contact.

- 1. The Indigenous Peoples of Alaska

- 2. Alaska Before the Russians: A Land Shaped by Resilience

- 3. Early Russian Exploration

- 4. Russian-American Companies

- 5. The impact of Russian colonization on the indigenous peoples of Alaska

- 6. Intermarriage and creation of Russian-Native "Creole" communities

- 7. Conflicts with Britain and the Sale of Alaska

- 8. Final Thoughts: The indigenous groups of Alaska

- Further Reading

1. The Indigenous Peoples of Alaska

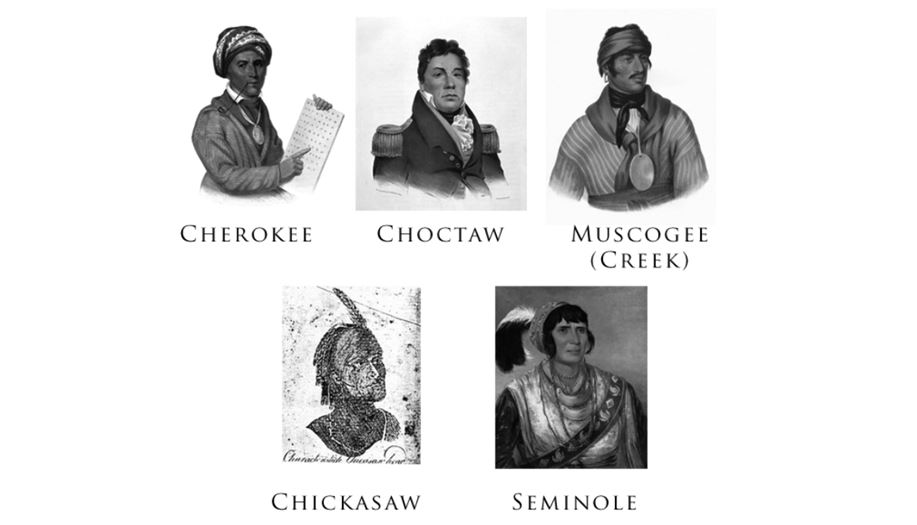

Before the Russians established a presence in the late 18th century, the lands that makeup modern-day Alaska were inhabited by various Native American groups for thousands of years.

The indigenous population consisted of several distinct ethnic cultures and traditions.

The most populous were the Inuit people, who dominated the northern and southwestern coastal areas.

Groups like the Yupik and Inupiat practiced seasonal hunting, fishing and gathering across the harsh Arctic environment.

In the interior regions of Alaska, the Athabaskan people including the Gwich’in, Koyukon and Tanana made their home alongside rivers and boreal forests. Living a semi-nomadic lifestyle, they survived by hunting caribou, moose and other land animals.

Other groups like the Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian and Eyak inhabited the rainforests of the southeastern Alaskan panhandle. They developed prosperous coastal cultures based on fishing, hunting sea mammals, and trade networks.

2. Alaska Before the Russians: A Land Shaped by Resilience

For millennia, Alaska’s unforgiving landscape teemed with life. Long before Russian fur traders set foot on its shores, a mosaic of indigenous cultures thrived in this vast and diverse environment.

From the icy Arctic tundra to the lush rainforests of the southeast, Alaska’s indigenous peoples developed sophisticated ways of life that were intricately woven into the land itself.

Skilled Subsistence Hunters and Gatherers

Alaska’s harsh climate demanded a deep understanding of the environment and its resources. Subsistence hunting and gathering formed the cornerstone of life for most indigenous groups.

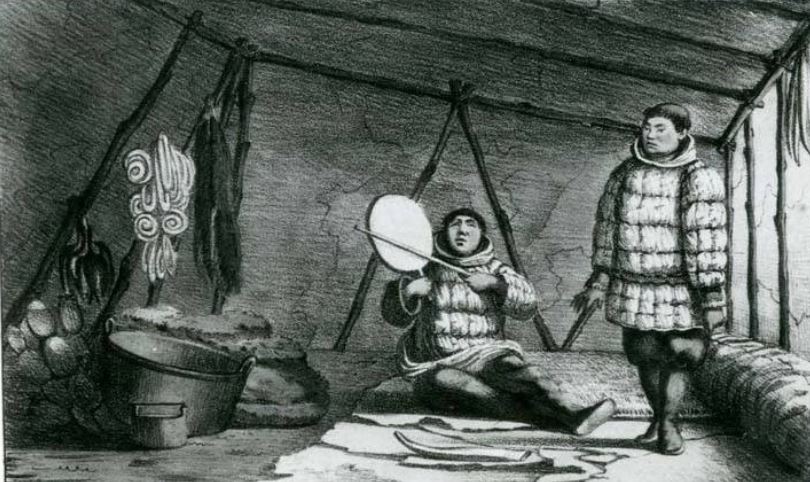

- Arctic Adaptations: In the unforgiving north and west, the Inuit and Yup’ik people honed their skills for hunting large marine mammals like whales and walruses. They also relied on caribou, seals, and fish, using ingenious tools like harpoons, kayaks, and fishing weirs. Their intricate knowledge of animal migrations and weather patterns ensured successful hunts and a sustainable way of life.

- Forest Dwellers: Further south, in the interior regions, Athabascan groups like the Gwich’in, Koyukon, and Tanana thrived by hunting caribou, moose, and other land animals. They lived a semi-nomadic life, following seasonal game migrations and utilizing a variety of tools like bows, snares, and deadfalls. Their intricate understanding of plant life allowed them to supplement their diet with berries, roots, and other wild edibles.

- Masters of the Coast: The southeast of Alaska, with its temperate rainforests and abundant waterways, fostered a rich maritime culture. The Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian people were expert fishermen, harvesting salmon, herring, and halibut using ingenious techniques like weirs, hooks, and nets. They also hunted sea mammals like sea lions and seals, and their complex social structures facilitated the sharing of resources and cooperation in hunting expeditions.

Complex Social Structures and Cultural Practices

Life in Alaska wasn’t just about survival. Indigenous communities developed rich social structures and cultural practices that fostered a sense of belonging and identity.

- Family and Community: Extended families formed the core social unit, with elders playing a vital role in transmitting knowledge and traditions. Sharing and cooperation were essential for survival in the harsh environment. Complex social hierarchies emerged in some groups, with leaders chosen based on hunting prowess, wisdom, or spiritual leadership.

- Spiritual Connection: The natural world held immense spiritual significance for Alaska’s indigenous peoples. Ancestral spirits and powerful beings were believed to inhabit the land and animals. Shamans, or spiritual leaders, acted as intermediaries between the physical and spiritual realms, performing ceremonies and rituals to ensure successful hunts, good health, and harmony with the environment.

- Artistic Expression: Rich artistic traditions reflected the deep connection between the people and their environment. Carvings, masks, and woven baskets showcased intricate designs and stories depicting their mythology, history, and connection to the natural world.

These cultural practices weren’t static; they evolved and adapted over time. Trade networks existed between different groups, fostering the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultural practices.

Living in Harmony with the Land

Sustainability was a core principle for Alaska’s indigenous peoples. They understood that the land’s resources were finite and practiced careful management to ensure their survival for generations to come. Hunting practices were selective, and populations of animals were closely monitored. Respect for the natural world and its bounty was woven into their belief systems and daily lives.

The arrival of the Russians in the late 18th century marked a turning point in Alaska’s history. The fur trade disrupted traditional ways of life, introduced devastating diseases, and forever altered the landscape. However, the resilience and cultural richness of Alaska’s indigenous peoples continue to inspire and inform the state’s identity today.

3. Early Russian Exploration

Russia was a relative latecomer to the exploration and conquest of the North American landmass.

As the 18th century dawned, Siberian hunters and traders had only begun pushing across the Bering Strait into northwestern North America in search of sea otter pelts.

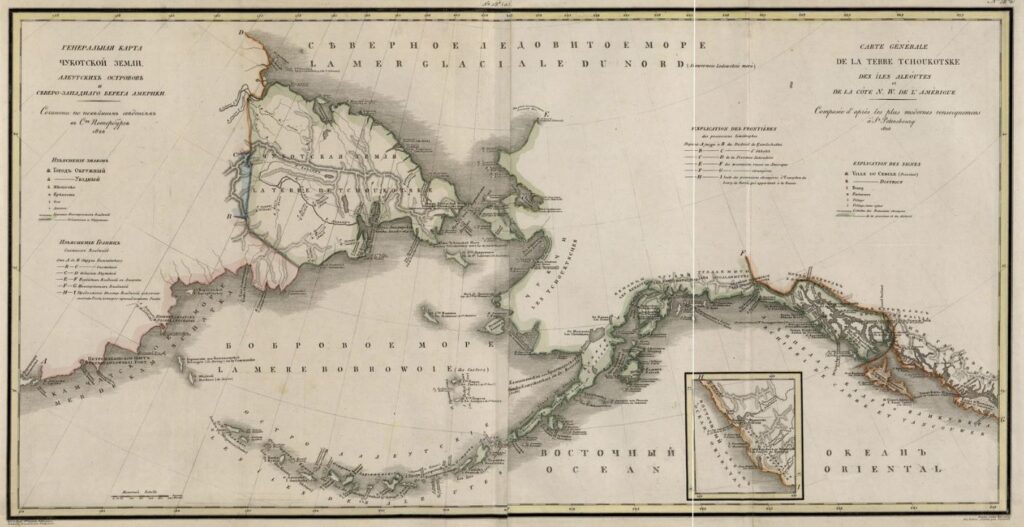

In 1741, the Danish explorer Vitus Bering was commissioned by Russia to map out the suspected waters separating Asia and North America. His two-ship expedition landed in southeastern Alaska, but ended in disaster with both vessels eventually being wrecked.

It took decades more before other Russian fur traders and explorers followed Bering’s path across the Aleutian Islands chain and established the first permanent Russian settlements in Alaska in 1784.

4. Russian-American Companies

To consolidate its claims and economic activities in Russian America, the Russian Empire granted a monopoly in 1799 to the Shelikhov-Golikov Company and its trade subsidiaries to manage the Alaskan territory as a private business venture.

Several of these Russian fur trading companies competed fiercely until Tsar Paul I merged them under a corporate decree into the new United American Company in 1800. For the next six decades, this conglomerate exercised monopolistic control over the Russian colonization and exploitation of Alaska.

Supported by Russian naval forces and promyshlenniki (Russian settlers and hunters), the Russian-American Company established settlements and fur trading posts stretching from the Aleutians to the Alaskan panhandle in the southeast. Russian Orthodox Christianity was also introduced during this colonial period.

5. The impact of Russian colonization on the indigenous peoples of Alaska

The arrival of Russians in Alaska in the late 18th century forever altered the lives of the indigenous communities who had thrived there for millennia.

The impact was devastating, marked by disease, violence, and the disruption of traditional ways of life.

One of the most immediate consequences was a dramatic population decline.

The Aleut people were forced into brutal servitude to hunt sea otters. This group suffered immensely. Diseases like smallpox, to which they had no immunity, ravaged their population. An estimated 80% of their population was wiped out.

This pattern repeated as Russians expanded – illnesses like influenza and whooping cough decimated other Native groups like the Tlingit and Haida.

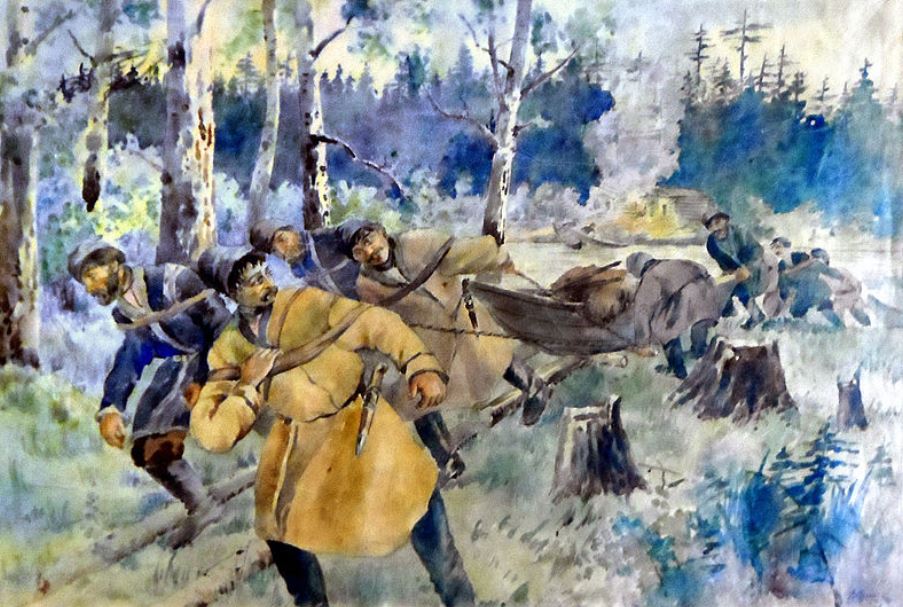

Beyond disease, Russian fur traders disrupted the delicate balance of Alaska’s ecosystem. Overhunting for furs depleted vital resources like fish and wildlife, jeopardizing the traditional subsistence lifestyles of indigenous peoples. This competition for resources often escalated into violence.

Russian forces used violence and subjugation to control Native populations, with attacks, rapes, and attempts to force assimilation commonplace.

The Russian-American Company prioritized profit over human rights. They exploited Native labor for fur hunting, with little regard for their well-being.

The legacy of Russian colonization continues to be felt in Alaska today. The dramatic population decline among indigenous communities left a lasting scar. The disruption of traditional practices and the exploitation of resources continue to have environmental and social ramifications. While the sale of Alaska to the United States in 1867 marked the end of Russian rule, the impacts of that era remain woven into the history and ongoing struggles of Alaska’s indigenous peoples.

6. Intermarriage and creation of Russian-Native “Creole” communities

History often paints Alaska’s Russian colonial era in stark strokes – fur traders, subjugation, and disease. But beneath this surface lies a fascinating story of cultural exchange and adaptation – the rise of the Creoles.

Creoles were born from marriages between Russian men and Alaska Native women. These peoples emerged due to a deliberate policy outlined in a 1794 letter by Ivan Pil. The goal? Fostering “mutually beneficial ties” between the communities.

While love may have blossomed in some cases, the policy’s core purpose was practical – addressing a chronic labor shortage.

This strategic intermarriage had a profound impact. It led to a flourishing Creole population that inherited a unique blend of Russian and Native cultures. Unlike their European counterparts, Creoles often spoke the local languages and understood the nuances of the Alaskan environment. This made them invaluable assets to the fur trade.

By the 1860s, Creoles had become the backbone of the Russian-American Company, the fur trading monopoly that governed Alaska.

They filled various roles, from managing outposts and trading with indigenous communities to working as skilled laborers and craftspeople. Their fluency in both Russian and Native languages proved crucial for communication and negotiation.

The Creoles’ contributions extended beyond the fur trade. They served as interpreters, mediators, and administrators, bridging the cultural gap between the Russian colonists and the indigenous population.

The story of Alaska’s Creoles is a reminder that history is rarely black and white. They were not simply pawns in a colonial game, but a vibrant community that played a pivotal role in the economic and cultural life of Russian Alaska. T

7. Conflicts with Britain and the Sale of Alaska

The initial years of Russian presence in Alaska saw minimal external resistance. However, by the late 1810s and 1820s, the British Empire’s westward expansion across Canada clashed with Russia’s claims in the Pacific Northwest.

This brewing rivalry, coupled with the growing presence of the United States, forced the Russians to re-evaluate their position.

Beyond external pressures, the financial viability of the fur trade became a concern.

The Russian-American Company, burdened by mismanagement and declining fur populations, struggled to maintain profitability. The vast distances and harsh Alaskan environment made permanent military defense a costly proposition for the Russian Empire.

Recognizing these challenges, the Russians adopted a more diplomatic approach.

Treaties with Britain and America aimed to clearly define and limit North American territorial claims. This reduced the risk of conflict and allowed Russia to focus on more pressing matters closer to home.

Ultimately, the Russians made the decision was made to sell Alaska.

The vast territory was seen as a drain on resources rather than a strategic asset. Russia deemed Alasaka expendable. In 1867, after negotiations, Alaska was transferred to the United States for $7.2 million, marking the end of Russian sovereignty on the North American continent.

8. Final Thoughts: The indigenous groups of Alaska

So while Russia maintained control over its Alaskan territories for several decades in the 18th and 19th centuries through the Russian-American Company, the lands were inhabited long before by various established indigenous groups.

From the Arctic Inuit and Yupik to the Athabaskan and coastal tribes like the Tlingit, these Native peoples had called the lands of Alaska home for millennia prior to the Russians or other European colonial powers arriving. Their deep ancestral roots as the original Alaskan inhabitants preceded any Russian claims or presence on the North American continent.

Further Reading

If you enjoyed this article, you may be interested to read more about Alaskan or American history or other territorial expansions, such as those from Mexico.